Spoonful of hate. Online violence against Ukrainian female journalists in YouTube comments

Spoonful of hate

Online violence against Ukrainian female journalists in YouTube comments

“Hahahaha. That lady is just a stupid chicken!” — such comments aren’t uncommon under YouTube videos of various media outlets in Ukraine. Aggression, harassment, sexism, and threats against journalists are all examples of gender-based violence online. Although YouTube has strict policies against hate speech, its moderation algorithms often miss it, removing hundreds of thousands pieces of content but leaving “just a stupid chicken” under videos from Ukrainian media. This may be due to the imperfection of the algorithms themselves or problems with “understanding” the Ukrainian language.

Note: This study analyzed comments written in Ukrainian and Russian. Some linguistic nuances may have been lost in translation, and certain terms or phrases might appear duplicated on the infographics.

The numbers are worrying: 81% of Ukrainian journalists surveyed by the Women in Media NGO in 2024 have experienced various forms of online violence. Most often, it's misogyny and defamation (spreading lies about a person) for the sake of professional discredit. But is it true that both remain unmoderated on Ukrainian-language YouTube and, like a fly in the ointment, regularly infect our information space with hate speech? We decided to verify this with data.

We took the top 10 most popular Ukrainian-language news YouTube channels, added the media YouTube channels from the “white list” (the most reliable media outlets in Ukraine), and selected this year's videos with at least one woman as a presenter or interviewer. A total of 2,300 such videos were posted on 15 channels, and we counted 285,000 comments on them.

This is the data we analyzed.

We processed all the posts using AI — we “fed” them into GPT-4o with a request to flag those with at least one of the ten types of online violence that occur in the comments. Namely:

- sexism

- misogyny;

- threats of death or physical violence;

- threats of rape or other sexual violence;

- hate speech;

- gender disinformation;

- doxxing (publishing sensitive personal information, such as home address);

- sexting/revenge porn (threatening to publish intimate photos, videos, etc.);

- gender-based trolling;

- defamation.

You can find a description of each type of online violence with typical examples at the end of the article. We found all these types in the comments.

It should be noted that some of them are a problem not only for women journalists, but also for men. However, we focused on female journalists, who had previously made up the majority in the media industry, and, for objective reasons, this share increased after the start of the full-scale invasion. By the end of 2023, 77% of journalists were women.

Data source: Playlists of the 10 most popular Ukrainian-language news YouTube channels as of September 1, 2024, and media channels from the Institute of Mass Information's “white list” for the first half of 2024, with at least one woman as a presenter or interviewer. In all videos from the selected playlists, the YouTube API was used to download the first-level comments (excluding replies and further discussion threads), leaving only those that were longer than three characters.

Channels analyzed: (sorted by the number of videos included in the analysis, largest first): Apostrophe TV, Hromadske radio, Espreso.TV, Channel 5, Censor.NET, BIHUS Info, Toronto TV, Ukrainska Pravda, Ukrinform, hromadske, Radio Svoboda, Suspilne News, Babel, Tyzhden.ua, Butusov Plus.

Research period: All comments on videos published from January 1 to September 1, 2024, as of the beginning of September (deleted comments were not included in the analysis).

Data analysis: Comments were classified using GPT-4o, using a prompt that included a description of each of the ten types of online violence, along with typical examples in Ukrainian and Russian.

Results highlights: GPT didn't do the job perfectly. We expected from the very beginning that it wouldn't distinguish well between harassment of journalists and harassment of, for example, guest experts. But sometimes the LLM responded to hate speech that didn't refer to gender. Or it highlighted comments where the hate speech was not directed at journalists or guests but at, for example, the key figures in anti-corruption investigations or the Russian army and occupiers.

Out of 456 randomly selected comments labeled as containing different types of online violence, 60 (13%) were misclassified. This means that we estimate that GPT-4o correctly identified the type of online violence in ~87% of the comments.

Separately, we asked the AI to flag comments that were most likely left by Russian accounts (for example, they used anti-Ukrainian rhetoric, Russian self-identification or symbols, or contained other features that would signal to the LLM the commenter's Russian origin). However, the quality of this classification was extremely low. It seems that GPT is still not very good at understanding the Ukrainian context.

9% of the 285 thousand comments analysed contained at least one type of gender-based online violence.

Percentage of aggressive comments under videos on YouTube channels

Is this too little or too much?

According to YouTube's anti-hate and harassment policies, they shouldn't have been there at all.

Most often, the comments contained signs of hate speech, threats of physical violence, and misogyny.

The most common types of online violence found in the comments

Misogyny — hatred, contempt, prejudice, and disgust for women.

Defamation — public statements aimed to harm a journalist's reputation.

Doxing — publishing (or threatening to publish) personal information for the purpose of pressure or intimidation.

Sexting / revenge porn — threatening to publish intimate photos, videos, etc.

Not all videos receive the same amount of hate. The most negative comments are left under those dealing with corruption, mobilization, or illegal travel abroad. Among the "record holders" in terms of the number of aggressive comments are, for example, BIHUS Info's video analyzing the activities of Ostap Stakhiv (a pseudo-lawyer who helps men to flee Ukraine illegally), Toronto TV's video about artists who have left the country, or hromadske's report from the recruitment office.

However, the average level of harassment doesn’t depend much on the “hype” and popularity of the video. It has rarely exceeded 20% of all comments and has remained below 10%. It doesn't matter if you have 100 comments or 1000 comments under your video.

The amount of aggression doesn't correlate too much with the "hype" and the total number of comments under the video

When you start reading those comments, the first thing that strikes you is the amount of hate speech and its blatant directness. And also the lack of restrictions on these comments by the platform.

keep scrolling ↧

In the comments under journalists’ videos, you can find…

the most common examples of swearing and obscene language,

words that are sexualized or refer to physiological or bodily aspects,

signs of dehumanization, equating with animals or their parts.

Hate speech is full of vivid adjectives

and verbs that often reproduce threats of death and physical violence.

Another characteristic feature of online bullying is the reference to body parts, often with the use of degrading and rude words. All of this is done to provoke a reaction and make the images more intimate, creating a sense of vulnerability and weakness in the target.

And here we have both well-established expressions like “blood from the eyes” (“Please, fewer quotes, my eyes and ears are bleeding from so many Russians”) and more targeted and conscious attacks on appearance (“What are these weathered lips of a blowjob girl”, “She's talking to him, and her nipples are so horny” or the emotional and metaphorical “She is sticking her stupid nose in everyone's ass.”)

Needless to say, not only the face or hands, but also the genitals are often involved.

Body parts most frequently mentioned by haters in the comments

Signs of online violence often manifest themselves in the way women are addressed. The use of certain words or phrases can be a way to devalue, demean, or distract from the importance of the matter. For example, sexist references such as “woman” (used with disdain in Ukrainian - “жіночка”) or “chick” demonstrate a desire to diminish the role of women. Another common tool is hate speech, which is used to depersonalize and demean journalists by referring to them with derogatory words such as “journo-whores” or “sluts.”

Still, we have a small victory: Ukrainian media videos were commented on 3.5 times more often in Ukrainian.

At the same time, there was less hate in Ukrainian than in Russian. This can be partly explained by the comments of Russians, especially under the reports from the Kursk region, who didn't bother to translate too much, for example, to wish Ukrainian journalists to be raped by the Russian army (and yes, YouTube also left these comments unmoderated).

Offline consequences of online violence

Gender-based online violence against female journalists isn’t a purely local Ukrainian phenomenon. According to a global study of online violence against women journalists conducted by the International Center for Journalists and supported by UNESCO in 15 countries in late 2022, 73% of respondents said they had experienced online violence in the course of their work. Online attacks have affected the professional reputation or work of one in ten media professionals. One in five said they had been attacked or mistreated offline due to systematic online harassment.

In Ukraine, the situation is similar: among media women surveyed by the Women in Media NGO, 14% of those who had experienced online violence reported that threats against them had moved from the digital space to the physical dimension.

This means that while offensive comments under videos may not seem as threatening, they are another step toward legitimizing and "virtualizing" violence.

But there is another, less obvious consequence of public online harassment of journalists. It has to do with the so-called "chilling effect," a situation in which online violence affects not only the journalists themselves, but also other women. That is, those who observe the situation from the outside. The result is a decrease in women's desire to pursue a degree in journalism or a career in journalism, an increased fear of publicity, and a desire to self-censor to avoid topics that could potentially trigger a wave of hate.

This means that aggressive commentators not only seek to discredit journalistic material, humiliate, disgrace and intimidate women journalists, forcing them to shut up or withdraw from public activities. They seek to discredit the profession of journalism itself, undermine trust in facts, devalue free speech, and limit active participation in public debate.

More on the devastating impact of online violence on the media can be found in a study by the International Center for Journalists (ICFJ) with the support of UNESCO. The OSCE Guidelines for Monitoring Online Violence against Women Journalists in Ukrainian are available here.

Moderation = YouTube's responsibility?

As stated in the platform's policies, YouTube does its best to limit hate speech, dehumanization, and harassment on the platform, which means not just videos, but all content, including comments.

“YouTube's priority is to ensure the safety of comments for all users, including protecting content creators themselves.” Both algorithms and personalized moderators help the platform do this.

The fact that the comment moderation algorithms do work is indirectly evidenced by “encrypted” comments that omit certain letters, use the Latin alphabet, or have an excessive number of spaces, even within words.

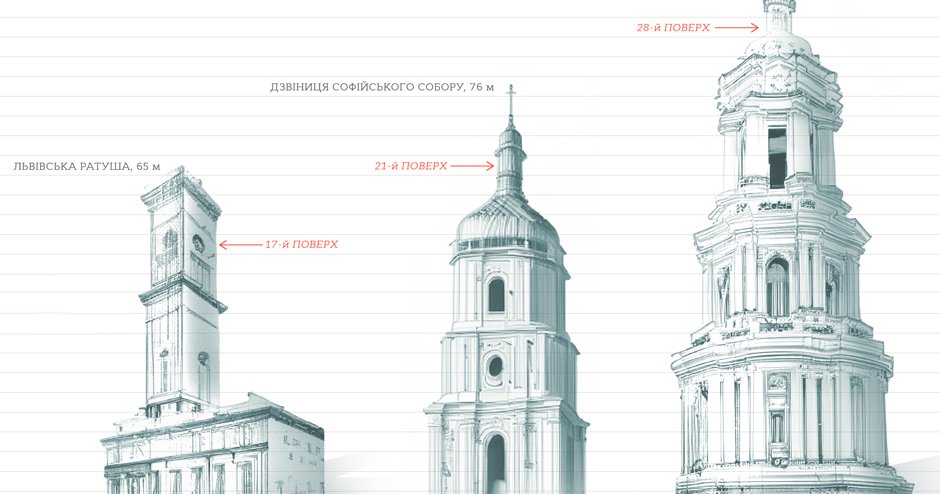

And while one could partially excuse the algorithms for their inability to read ciphers that only Ukrainians understand, the visualizations above demonstrate that the problem goes much deeper. It's partly related to language: YouTube, like most Western-centered platforms, “understands” English best. And in the case of less popular languages, as we know, it may even recommend videos that violate the platform's policies. For example, videos that recommend treating cancer with baking soda.

However, there is another side of the question: Ukrainians know better than anyone how often moderation algorithms work against our attempts to tell the world about the war. Similarly, in our study, GPT sometimes made mistakes, for example, when it labeled comments criticizing sexist remarks, phrases reminiscent of massive cases of sexual violence during the occupation, or sarcasm as gender-based online violence.

A lack of understanding of the context in a full-scale war creates a huge gap between what seems obvious to us and what is “obviously unacceptable” from the point of view of “peaceful” Western-centered algorithms. And for that matter, it is much safer for the reputation of the platform to let hate speech through than to accidentally ban completely neutral comments.

Given these imperfect algorithms, YouTube's settings today allow you to improve the situation a little bit yourself. For example, by completely closing comments on videos or through the mechanism of complaints about offensive content, which, by the way, can not only counteract specific information attacks but also help to train moderation algorithms using examples from the Ukrainian information space.

In addition, there is another way that channel and media owners can limit the ability to leave hateful comments under their videos — by creating their own blacklist of words prohibited in comments.

On your channel, you can define words that will cause comments to be reviewed by the channel administrator before they are published (or never published). For example, by adding certain words from our visualization of examples of hate speech in comments to the list.

And it seems that for now, the only way to remove this spoonfull of hate is in our hands.

What is online violence and what can it look like in comments?

Online violence manifests itself in various forms and types, which rarely exist in isolation or in a pure form. They are often intertwined or combined in a single comment or message. Nevertheless, distinguishing between them is key to categorizing and better understanding the threats posed by each form of violence.

For this study, we asked GPT-4o to mark comments that contained at least one of the ten types of online violence. In the spoiler for each type, you can see the most typical examples of its use (the original vocabulary and punctuation are preserved, but to protect journalists, we have replaced the names of editorial offices and names with *****).

The material was prepared by Texty.org.ua and the Women in Media NGO as part of a project in partnership with UNESCO and with the support of Japan. The authors are responsible for the selection and presentation of the facts contained in this material. The views expressed are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position of UNESCO or Japan.