How Russians fabricate cases against Ukrainian prisoners

Texty.org.ua has already written about how Ukrainians are being slowly killed in Russian torture chambers. In this article, we describe how cases are fabricated and trials of Ukrainian prisoners are held. We talked to prisoners who have gone through all the circles of hell in the occupiers' courts, as well as to the coordinator of the project "Search. Captivity". Within the framework of this project, Russian human rights activists, lawyers, and volunteers are trying to ensure the legal rights of Ukrainians (combatants, civilians, and children) who are in captivity.

For Ukrainian prisoners, everything starts with the places of detention. Some are immediately placed in pre-trial detention centers, others in some other little-known areas of the modern Russian Gulag camps. Floors, buildings, or even entire facilities of the Russian penal system are allocated for the detention of prisoners, where everything is designed to break a person.

It seems that the Russians didn't have to invent anything special. Most likely, all of these torture rooms, "confession playgrounds," have been functioning normally in Russia in one form or another since the Soviet era. This network is in full work today, probably in the same way as in Stalin's time.

Interestingly, a "piece" of the Ukrainian penitentiary system, namely employees of various Ukrainian penitentiary institutions, pre-trial detention centers, and courts located in the occupied parts of Donetsk and Luhansk regions, has very organically merged into this system of torture.

The coordinator of the project "Search. Captivity", who asked to stay anonymous: "The head of the Investigative Committee of the Russian Federation, Alexander Bastrykin, said that almost three thousand criminal cases had been opened, as he put it, "on the facts of Ukraine's crimes in Donbas. They can't just be closed. They must end in a trial.

For a trial to take place, an investigation is needed. The investigation must fabricate a criminal case.

Fabrication of the case is 95% at the stage of investigation.

They can start fabricating a criminal case literally from the moment of detention, or after any amount of time. So, for example, at the trial, the documents show that a person was detained in September and was placed in a pre-trial detention center only in January of the following year. Where he was from September to January is a complete mystery. Because officially, he was nowhere to be found. That is, either the person was in the basement or under the military police in one of the detention centers, where they were already working on that person, fabricating a case."

Access to the occupied territories is complicated. According to Russian law, this is a "zone of a Special Military Operation." Therefore, it is not easy for the "wrong" lawyer to get there, although, surprisingly, there are still some independent lawyers in Russia, as it was in the Soviet era.

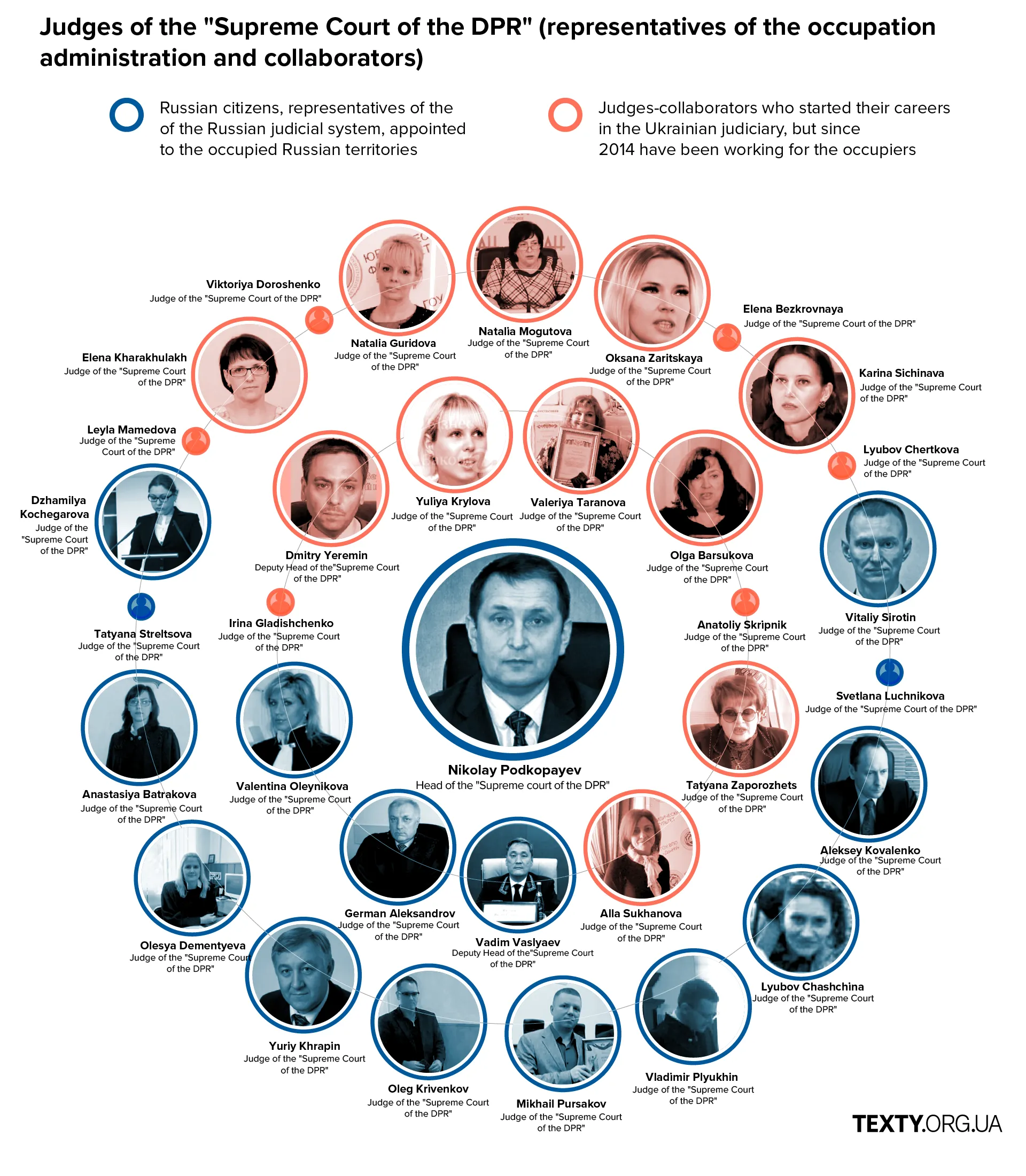

"The main court is the "supreme court of the DPR" (Donetsk People's Republic). Sometimes, the cases of the "supreme court of the DPR" are brought to an end in Rostov, in the Southern Military District Court," our source continues." We remember that most of the fabricated cases are so-called war crimes. Accordingly, they have jurisdiction in this court. Ukrainian prisoners are held in two of the oldest buildings in Donetsk detention centers 1 and 2.

The people currently in charge of the detention centre were in charge of it during the Ukrainian era, and now, during the occupation, they hold the same positions. We are talking about entire dynasties. This is the case not only in the detention center but also in other law enforcement agencies.

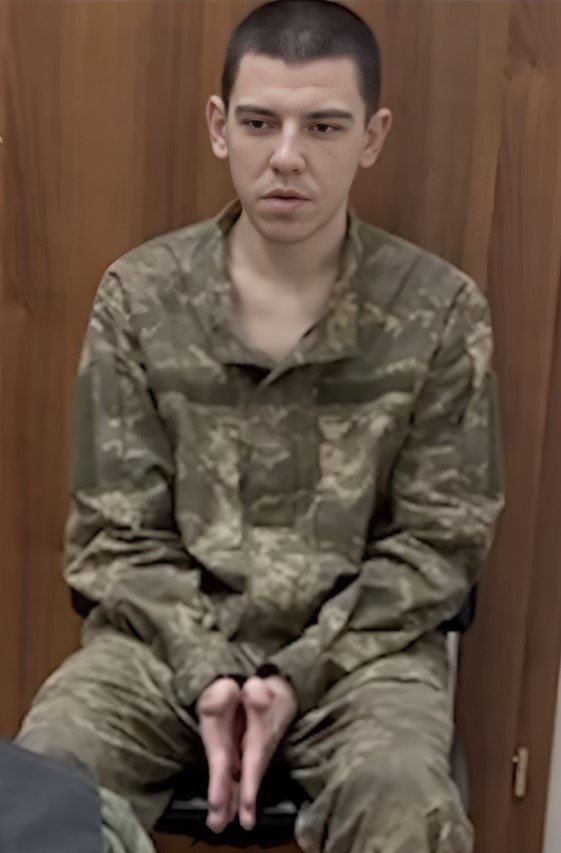

They can keep the child until they turn 16. They are given a Russian passport and then prosecute

Today, both military and civilians are involved in these cases. As for civilians, Ukrainian civil servants and civic activists are at risk. There can be random people who, for example, were reported by neighbors, even children.

That's right, children are also defendants in lawsuits. And here, the Russian authorities can behave in a completely shameful manner. They can simply hold a child until they turn 16. They give them a Russian passport and then try them for treason."

Torture, extracting confessions

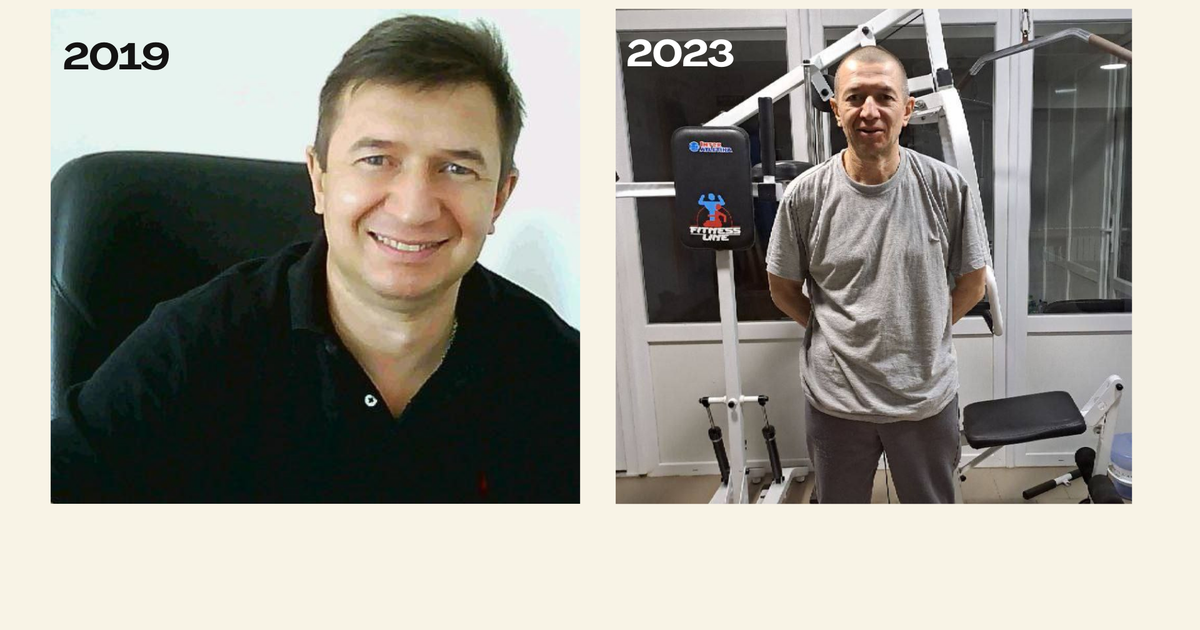

Serhii Taranyuk, a marine and commander of an airborne company, has been in captivity for almost two and a half years. He was captured in April 2022 in Mariupol and released recently, in September 2024.

Serhii Taraniuk: When I was already in Kamyshyn detention center No. 2 in October 2022, I was summoned for interrogation. First, the FSB (Federal Security Service of Russia) interrogated me, then the local operatives. They accused me of allegedly ordering my comrades to shoot three civilians. They just wanted to ask us for some help, and I gave the order to shoot them.

It was about some abstract civilians. Some unknown civilians whose body wasn't found. No ammunition was used in the case.

They demanded a confession, and then they just started beating it out.

Every day they called me for different tortures. For a week, I was almost not allowed to sleep and was constantly forced to do sit-ups and push-ups. The light in the cell is always on, there is a peephole in the door, and they see you and order you to squat or just stand at night. From time to time, they would ask me if I would sign a confession. When they heard a refusal, they ordered me to do sit-ups again.

We weren't fed for three days

And you are exhausted because you are hardly fed. And if you refuse, they take you out and beat you. They were beating you constantly — with hands, feet, rubber truncheons. For a week, we were fed only once a day, and sometimes, we weren't fed for three days.

All this lasted for about a month. I held on, I held on, but at some point, my strength just ran out. And I said that yes, I did it, I gave this order. They gave me a sheet of printed text, a regular A4, where everything I had to say was written.

Vladyslav Stryukov is also a marine, he was a company commander and was held in captivity for almost two and a half years. He was sentenced by the "supreme court of the DPR" to 20 years and then re-sentenced with a total sentence of 24 years in prison.

Vladyslav Stryukov: There was an investigator from the Investigative Committee, if I'm not mistaken, from Volgograd. As soon as they brought me to him, he put a knife bayonet on my leg. He said, "Go ahead and tell me how you killed everyone, how you gave the orders to shoot. I told him: I have nothing to tell. Then he started hitting me with a chair, demanding a confession.

He brought some men and said that they would kill me right here. Then he opened the window, scared me that he would throw me out. Then he went somewhere, came back completely drunk, and gave me a phone call home. This, by the way, was the only time during my captivity when I was allowed to call home. Then he beat me again, demanding that I write a confession. This continued until another investigator came and took me back to the cell.

But in the Kamyshyno, it was a disaster. When you go there, they immediately throw you on the concrete and start beating you. I have never been beaten so severely. They used everything: legs, arms, stun guns, rubber truncheons, wooden hammers, and set dogs on us. To understand how long it lasted, we were brought there at noon in the night from October 2 to 3, and I entered the cell at 12 o'clock in the afternoon on October 3. And I was not the last one. The same representatives of the FSIN (Federal Penitentiary Service in Russia) were beating me, and some of their special forces were with them, all in balaclavas.

There was a man in a white coat who looked like a medic. He said he was a doctor. He was running between those who were being beaten, asking who was hurt. If someone responded and asked for help or if someone was already unconscious, this doctor would run up to the victim and say, "Oh, I'll cure you now!" and beat him with a stun gun.

The doctor would run up to the unlucky person and say, "Oh, I'll cure you now!" and beat him with a stun gun

In general, they beat me there all the time. Every day and for any reason or even for no reason, whether you were doing something or just going to the bathroom. They would beat you until you fainted or started to suffocate.

Vladyslav Stryukov: "In the Kamyshyno detention centre, they didn't just beat us. There was a real torture room — a separate place for it. Four people interrogated me. One was a local from the detention center; another was in military uniform and kept asking about our plans and positions. The other two were in civilian clothes, most likely FSB officers or from the Investigative Committee.

In charge of the interrogations were these plainclothes men. They immediately started asking me how I was captured. I told them, and one of them said, "No, buddy, that's not good enough; let's try again." I told them the same thing again, and he said, "You probably didn't understand." And they immediately started beating me with a stick and a taser. After they beat me, they interrogated me again: tell me how you killed. I said that I didn't do it.

And then one of the men in civilian clothes offered to take me through a lie detector, as he put it. Only it was not a lie detector at all. They brought a "tapik" (military field phone). There is an inductor with a handle, and you turn the handle, and an electric current is generated.

I was ordered to take off my pants and they tied a wire from this "tapik" to my penis. They said, "We will use a lie detector to check whether you are telling the truth or not. I told them the same thing, and they electrocuted me. I tell them the same thing again, and they shock me again. And again, and again... All this went on for about two hours.

Then they started saying that my commrades had already reported me, that I had given the order to kill. I again said that this didn't happen, and they tortured me for about an hour. Then they threatened me that I wouldn't leave here until I wrote a confession.

Finally, I felt I couldn't take it anymore, so I asked them what I should write. And they said, "Don't you understand? Think of something. We need to know the truth, and we're going to get it from you. And again, they began to shock me and, at the same time, tell me what I should write. "Tell the truth, how you gave your soldier the order to kill a civilian."

I started writing it. And they said, "No, that's nonsense. Write that you received this order from the commander and gave it to your soldier." I said that I had no contact with the commander at all. The FSB staff said, "No, go ahead and write, and one is not enough for me, buddy. Write for two."

I started to refuse. Then they electrocuted me again and beat me a little more. I couldn't stand it anymore; I said: let me write that I killed the whole of Mariupol myself; let's just finish it. They tortured me for some time, and then they remembered that they had my commander as a prisoner also. They said they would give me time to rest a bit, and then I had to report my commander.

They took me to a cell, gave me something to eat, and then brought me back to the third floor, where they had a torture room. When I was taken for interrogation, they always put a pillowcase over my head, but when I got to the torture room, I realized by the sounds and voices that my commander was lying on the floor and was also being electrocuted.

They immediately demanded that I report him, that it was he who gave me the order to kill the civilian. I started telling them that the order was allegedly given to me through a radio station by someone but I'm not able to say who it was. This made them extremely angry. In the end, they put me on the floor next to the commander and tied an electric wire to our genitals.

One of them said: "I'm going to give you an electric shock, and you shout that you're happy." And so they gave us electric shocks, and we screamed: "We are happy! We are happy!"

They gave us electric shocks, and we screamed: "We are happy! We are happy!"

When the power was turned off, they started again: write a confession. Then they turned to my commander, saying, "Choose which of you will go to your cell and which will stay here. And he said: "I'm staying; let the kid go." I was taken to my cell, and he was left in the torture room.

As a result of all this torture, I confessed that I had allegedly given two orders to my soldiers to kill civilians.

After that, a new life began for me in the detention center. Everyone there knew that a civilian murderer was sitting there. I have now received increased attention. The local prison bosses didn't miss a single chance to get back at me. Everyone was standing and beating me. They beat me as hard as possible. In short, I was getting the worst of it.

Serhii Taraniuk: The Russians wanted to hear that you or someone from your entourage shot civilians or a car with them. They start calling prisoners, beating them. And, of course, there are people who can't stand it and start making up stories that someone shot or raped someone. And that's it; then they call the person they pointed to and torture them until they get a confession.

And then they ask: who is your commander? You couldn't have made the decision to shoot civilians yourself, could you? You must have been given this order by your commander.

At the same time, the commander is being interrogated. They also torture him and then say: you didn't give this order yourself; your commander gave it to you. This chain can go up to the battalion commander. And they start judging everyone along this chain. And then you look at those people and realize that they were all tortured. The way a person behaves and how intimidated they are, you can tell that they were tortured.

The game of investigation

After the first confessions are taken, the process of documenting these "confessions" of the tortured begins. Investigators from the Investigative Committee of Russia take over the case, and it seems to become more legitimate. But, like everything in Russian reality, this is just a delusion.

Serhii Taranyuk: Investigators will appear when you have already signed a confession. They ask you more questions about everything. It's up to you to come up with more details about where it allegedly happened, to show on the map where the imaginary civilian was, where your position was, and so on.

And if you told them something wrong, they turned to local officers if they didn't like something. And they start, as they say, "working" with you. Again, it's all over again: beatings and torture so that you say what they expect so that the case can move faster.

Vladislav Stryukov: A lieutenant from the Investigative Committee came to see me. He asked me if I had written two confessions and if they were true. I said no. And he said: no, you don't understand why I'm asking you. I will turn on the camera now, and you will say what you wrote. Or you will go back to the third floor. Then he demanded that I tell him all these fictional details on camera. When I forgot something, he let me read from the case file but told me to retell it in my own words.

He showed me a photo of a silhouette, allegedly a civilian we killed, and ordered me to circle where the bullet hit. I pointed at random, and he said no, let's go to the left. It was the same with the map. He brought the map, I pointed somewhere, and he said: no, two houses to this side. I circled it and signed it.

Then I had an examination, supposedly with a real lie detector. They connected some sensors to me and said they would check whether I was telling the truth.

I asked the person who connected the lie detector: should I tell the truth, or should I tell like it's supposed? He said, "Now, just a minute. He took it and left, and another one came in instead, who immediately asked me: have you forgotten what you have to say, or do you need me to remind you?

I asked the person who connected the lie detector: should I tell the truth, or should I tell like it's supposed?

I said, "Okay, I understand; send back the one who came out. The specialist came back and asked me questions, and I had already memorized the answers, but I still didn't know what the detector actually showed.

They also brought a lawyer. He said that I had the right to make a phone call, and when I wanted to call my wife, he said there were no TV or phone towers left in Ukraine, so there was no connection. And once he told me that I would put all of you in jail, but it would take a very long time. In the end, he waited until I wrote that he was familiar with the case file, and he said that we wouldn't see each other again.

But the ruthless cruelty of the Russian punitive system is that it never lets its victims out of its clutches completely and tries to use them again and again. This was the case with Serhii Taranyuk.

Serhii Taranyuk: In December 2023, I was taken to Detention center No.2 in Taganrog. They tried to fabricate something else. I was sent to the detention center again. The torture began again. It had its specifics there. They hung me by my feet in handcuffs to a special bar, and I hung my head down. They wanted to get a confirmation from me that I had allegedly given an order to shoot someone . Then they tried to accuse me of raping. But I said I wouldn't take responsibility for anything.

In general, it was terrible in Taganrog detention center. There were checks twice a day. A check was when the cell is opened; we run out into the corridor. They just started beating us. They might also let the dogs down, and then they beat us again, including with rubber truncheons. That was done for no reason, every day. The food there was also very poor, even for a Russian detention center.

As we were preparing this material, we learned about the death of Ukrainian journalist Viktoria Roshchyna, who was once held in Taganrog detention centre No.2.

War criminals in balaclavas

This raises an interesting question: who are all these people outside of the torture room? While photos of the heads of the detention centers and their data can be found quite easily, it is pretty difficult to understand whose face was under the balaclava or medical mask.

At least it's possible to understand which of the Russian institutions is most into torture and coercion of false confessions from prisoners. We're talking about three groups, and they can probably be directly called war criminals. According to the Rome Statute, a war crime is the intentional deprivation of a prisoner of war of the right to a fair and ordinary trial.

As for the detention centers' operations, this is the lowest category in the punitive hierarchy. They can rather be called laborers of torture. These are the people who beat out the necessary confessions from prisoners with their fists, feet, and other tools. They do all this on the orders of their more "advanced" colleagues from the FSB and the Investigative Committee. These two categories are actually in charge of the whole process.

If you monitor the Russian "news," it may seem that it's the Investigative Committee of the Russian Federation that plays the first role in the prosecution of Ukrainian prisoners. Bastrykin holds one committee meeting after another, where he demands to investigate the "atrocities of the Ukrainian Nazis." The committee has even created a special position — the head of the War Crimes Investigation Department.

It's evident that the committee is attempting to replicate the processes currently conducted against Russia by international institutions or even the post-World War II prosecution of Nazis. However, they are failing miserably.

Let us recall that the cases they present lack both evidence and victims, and their progress is fueled by extracting confessions from prisoners through torture and the puppet-like nature of Russian courts.

The intellectual capacity of the Investigative Committee can be illustrated by the fact that Bastrykin himself is the author of the widely known claim that former Ukrainian Prime Minister Arseniy Yatsenyuk participated in battles on the side of Ichkerian rebels in Grozny in 1994.

Perhaps the greatest secret of Russia's Investigative Committee lies in the figure behind the investigator in a green uniform: a figure in civilian clothing. This figure is an FSB agent. Accounts from prisoners confirm this: interrogations always involve individuals in civilian clothing who issue all the commands.

However, both FSB agents and investigators not only give orders but actively participate in torture themselves, sometimes employing "innovative" methods and inventing new forms of abuse.

According to the coordinator of the "Search. Captivity" project, it was an FSB agent who devised a new, "media-oriented," if one might say so, method of torture. It has now become quite popular:

"A person is tied to a chair, their legs and arms taped to the legs of the chair, and they sit with their head down. Then, they are struck on the back of the head with a water bottle until everything back there is covered in blood. But, importantly, the front of the person — their face — remains completely intact. This way, propaganda videos or testimonies can still be recorded with them. The back of their clothing sticks to their body due to the blood, but from the front, they look unharmed."

The back of their clothing sticks to their body due to the blood, but from the front, they look unharmed

Descendants of Joseph Goebbels

Of course, the court spectacles arranged by the Russians would be utterly unnecessary without media coverage. Without it, extracting confessions, torturing, and the judicial show would have no purpose. It is Russian media, or to be precise, propagandists, who are responsible for the crimes committed by Russians against Ukrainian prisoners.

Vladyslav Stryukov: "When I was in Donetsk's detention center, their senior officer once came and said they needed someone to talk on camera about foreigners in the Ukrainian Armed Forces. They claimed, "We know you had them." Then he immediately started threatening us: "If you don't cooperate willingly, it will be done the hard way."

In short, they took me and another prisoner. We came out, and there was already a journalist with a film crew waiting for us, as well as an FSB agent, of course, wearing a balaclava. How do I know he was from the FSB? Another prisoner recognized him by his posture; he had interrogated him earlier. The film crew appeared to be from Russia Today.

But they didn't question me — it was the same officer from the detention center.

They asked me about mercenaries in the Ukrainian Armed Forces. They even told me I could respond freely without any pre-prepared text. I replied that we had no mercenaries. Then he brought up British citizen Shaun Pinner, who had served with us. I replied that he was just like any other Ukrainian Armed Forces serviceman, with a military ID and a salary.

They didn't like my answer at all. The people from Russia Today gave the officer a very expressive look, "Who did you bring us?'"He immediately declared that I was talking nonsense and needed to say something else — for instance, that foreigners were paid extra. I replied that this wasn't true. But they said that, regardless, the report would state that I had said it.

According to Serhii Taranyuk, he was also once sent for an "interview" with Russian journalists. But his case was even simpler: they just handed him a sheet of paper with theses he was supposed to recite on camera.

The Judicial show

This brings us to the spectacle for which all this was conceived: the trial of Ukrainian prisoners of war. Though calling it a "trial" is quite a stretch. It's more of a staged performance whose primary purpose is to legitimize yet another set of Russian war crimes and their expansionist policies.

This was the case in the 1930s, and it's the case now. It seems likely that Russians had the show trials with prosecutor Vyshinsky (a state prosecutor of Joseph Stalin's Moscow Trials and in the Nuremberg trials) in mind when they began organizing their first court processes against Ukrainian prisoners of war.

The main focus is placed on Mariupol. Since the destruction of this Ukrainian city by Russian forces, a massive propaganda campaign has been underway in Russia to whitewash the actions of the occupiers and shift the blame for the destruction and the killing of civilians onto Ukrainian soldiers (read more about this here). The basis of this campaign is the organization of such show trials.

See also: Colonization: How Russia is encouraging the settlement of occupied territories by its citizens.

Initially, the occupiers likely planned to copy Stalinist show trials in both scale and narrative. However, at some point, things went awry.

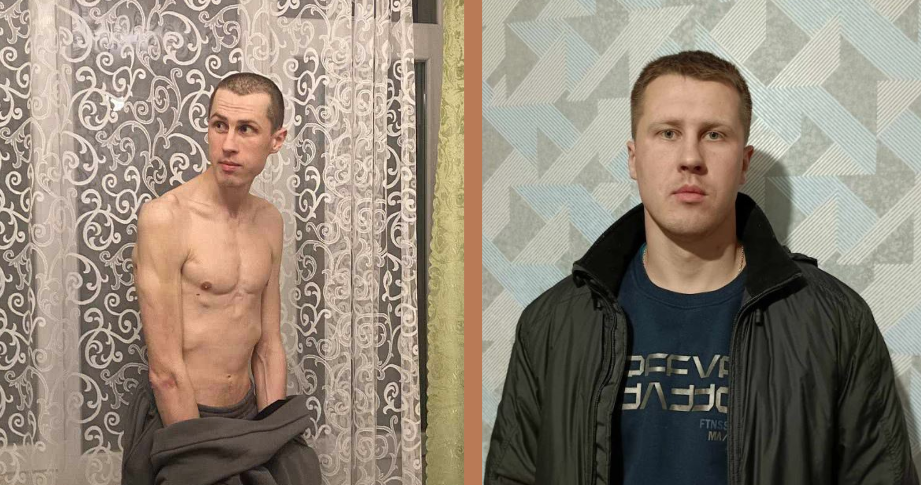

"The main task is to showcase the alleged atrocities of Ukrainian soldiers in Mariupol," says the coordinator of the "Search. Captivity" project. "But this is difficult to execute. Even organizing such a process is challenging. They’ve already tried this — remember how they organized mass trials at the very beginning? But they stopped. They thought they’d create something like the Nuremberg Trials, but it turned out the opposite. The alleged criminals they paraded publicly looked as though they had been through hell. Severe weight loss of up to 50%, facial expressions, bruises all over — that’s what everyone saw when they were brought into the courtroom. So they abandoned such mass theatrical trials and now conduct them mostly behind closed doors."

However, despite giving up on mass trials, the occupiers haven't abandoned the idea of prosecuting Ukrainian prisoners altogether. These trials continue to take place.

Vladyslav Stryukov: Before the trial, I was taken to the Donetsk detention center. Here, they yelled at us but didn’t beat us. We guessed they didn’t beat us because we still had to appear in court. The detention center staff constantly repeated, "We’ve been forbidden to even touch the five of you." They seemed quite upset about this prohibition, as if they had been stripped of some kind of right.

They said: "We’ve been forbidden to even touch the five of you." They seemed quite upset about this prohibition

I was tried in the "Supreme Court of the DPR." There were three court sessions, after which I was sentenced to 20 years in a strict-regime colony. During the trial, we were held in a cage, seven people in total: me and those I had allegedly ordered to kill a civilian.

There were also prisoners accused of beating a Russian captive. Of course, this was just as much of a staged investigation as ours. The accused in this case weren't connected to one another in any way and came from different units. The investigators even twisted the case so that one man, who allegedly beat the captive, was the same soldier I had allegedly ordered to shoot a civilian.

There were lawyers in the case as well. In total, six lawyers represented the seven of us. One lawyer represented two defendants. We asked them to at least send some kind of photo to Telegram or at least confirm that we were alive. The response was: no, you’ll be shown on the news anyway. We asked what they could do at all. The answer was: nothing, our job here is just to sit.

The lawyers responded: "Our job here is just to sit."

Some lawyers didn’t even know what to do. They said: we don’t know what to do, how to act, or what to say here. The prosecutor replied that they didn’t need to say anything at all; they were only present because the law required defenders to formally participate in court proceedings.

The trial itself resembled an old TV show with staged court hearings. Everything here was made to resemble it as much as possible — a cheap circus with cheap actors. The only thing missing was a gavel being struck on a table to complete the resemblance. You just sit and watch as they all play their roles.

The prosecutor reads the charges. The lawyer says, "No objection." The judge: "Accepted." The only variation was when one of the lawyers might say something like, "Your Honor, please consider that the defendants acted this way because they were forced to by the Ukrainian Nazi government."

This theatrical performance ended with me being sentenced to 20 years. As it turned out, they didn’t find a body, so the case was reclassified from "murder" to "attempted murder." And since we were to be declared criminals anyway, the verdict included wording to the effect that we hadn’t killed the fictional civilian not because we didn’t want to, but because we couldn’t. In other words, we allegedly tried to shoot the civilian.

After this, I was returned to the detention center. Later, I was taken to another trial because, supposedly, I had ordered the execution of two more civilians.

An investigator came and said, "You signed two confessions, so now you’ll be tried for the second one." But this time, the atmosphere was more relaxed. The investigator was from St. Petersburg.

There was also a bizarre episode in the case: I had allegedly ordered someone to shoot a civilian with a Kalashnikov rifle from a distance of 800 meters, while the civilian was moving. This was absurd in itself — it’s impossible to hit a moving target from such a distance with a Kalashnikov. I told them so, of course. To which they replied, "We understand everything, but that won’t save you." I asked if I’d get a life sentence for this. They said no because they still hadn’t found any bodies. So once again, it was considered an attempted murder.

I was to be tried in the same "Supreme Court of the DPR." I was taken to court on June 4, 2024. In a year, everything had changed there — the actors had become more professional. It seemed less staged. They even improvised some of their own lines instead of reading only from a script.

"In a year, everything had changed — the actors had become more professional."

As for the lawyer, he genuinely tried to defend me. But I asked him to remain silent because I already knew the tendency: if the court sent the case for further investigation, I would most likely be taken from the DPR to the detention center in Taganrog and subjected to electric torture again. I’d heard about the torture room there. People said screams could be heard from it. Apparently, it was set up in a gym with a pull-up bar. I was supposedly being tried for another attempted murder, and after further investigation, who knows what else they would have pinned on me.

In short, when the court session began and the judge entered, I asked him to just sentence me and end it as quickly as possible. Within half an hour, the verdict was announced—24 years of imprisonment, effectively adding four more years to the previous 20.

Serhii Taranyuk: In the morning, a convoy arrived and took me to their so-called "Supreme Court of the DPR." The hearing started at 10:30 a.m. Their judge, prosecutor, and assistant were present. The session lasted two hours, after which I was placed in a holding cell. I sat there for several hours before being brought back to the courtroom, where the sentence was read: 29 years in a strict-regime colony.

On a humorous note, I had a lawyer, a man about 55 years old. He just sat there and said he agreed with everything. Later, however, he did provide some sort of document regarding damaged property — apparently about a car we allegedly shot at. In the end, the court decided that I must compensate for it as well, to the tune of about a million rubles. And that was it.

"Supreme Court of the DPR" in faces

The "Supreme Court of the DPR" is essentially a conveyor belt for producing court rulings tailored to the needs of the Russian authorities and their propagandists. However, Texty.org.ua decided to investigate who exactly is behind this conveyor belt—who are the people deciding the fates of hundreds of Ukrainian prisoners of war and civilians today.

Interestingly, the staff of this punitive body includes both Russian judges appointed by the Russian authoritarian leader Putin in 2023 and former Ukrainian judges who, after 2014, switched to working for the occupiers. These individuals now, without batting an eye, hand down massive sentences in fabricated cases to their own compatriots, whom they have, in the truest sense, betrayed.

Texty.org.ua also asked the coordinator of the “Search. Captivity” project to briefly describe the activities of their initiative.

"We have more or less formed as a legal community in Russia since 2014. A group of people with a conscience, ready to take risks and who understand the true purpose of the legal profession.

Russian legislation is structured in such a way that foreign lawyers have no authority in Russia. Only Russian lawyers can work there.

We now have significant experience in defending prisoners of war and civilians because we do not refuse anyone. We not only defend prisoners but also locate them, or at least attempt to find and obtain official information if a person is missing.

Anyone can contact us regarding the protection of Ukrainian prisoners: relatives, friends. We never refuse. All we need is a name, surname, date of birth, passport number, etc., and we start working."

Contact us at: https://poshuk.io.

Texty.org.ua also expresses gratitude to the Association "Marine Corps Strength" for their assistance in preparing this material.