"Everyone said to leave Ukraine". Report from Munich, where Ukrainians young men are fleeing to

Three months ago, Ukrainian government changed the rules for crossing the state border during martial law. Men aged 18–22 were allowed to leave the country. "Stop this flow", "Young Ukrainians are leaving for Germany en masse", the press sounded the alarm. Photos circulated on the internet showing people in sweatpants standing in line at refugee centers. Texty.org.ua traveled to Munich to see what was happening with our own eyes and talk to young Ukrainians who had taken advantage of the opportunity to leave Ukraine.

In early December, Munich is already slowly preparing for the Christmas holidays: markets are opening in the city, and more and more colorful lights are being lit. The first snow has fallen.

The Ukrainian community in Munich is also preparing for the holidays. Local Facebook communities invite their compatriots to holiday markets and Ukrainian-language children's celebrations. However, this year, Christmas announcements are interspersed with dozens of messages from young Ukrainian men. 20-year-old Slavik is looking for a job. He says he has "some experience in construction". 22-year-old student Oleh, who "without bad habits", is looking for an apartment somewhere in the region of Bavaria.

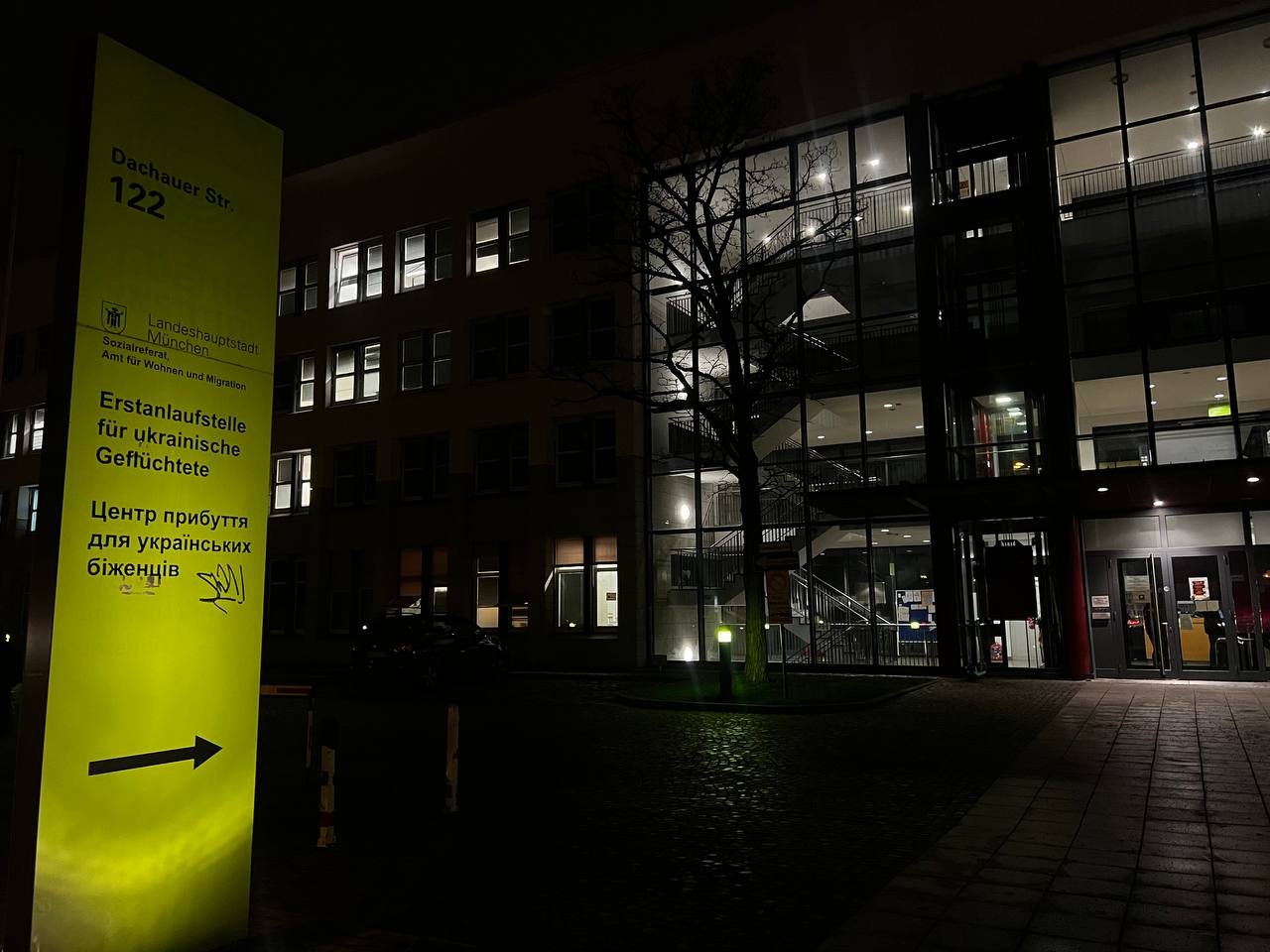

Most of them took advantage of legislative changes that allowed men aged 18 – 22 who are subject to military service in Ukraine to travel abroad during martial law. This is how they ended up at the refugee center in Munich — the first reception point on the "European" route for young Ukrainians.

Andrii, 20

Andrii emerges from a modern, massive gray building that resembles a university or hotel. The 20-year-old from Odesa arrived at the refugee center at 4 a.m. today.

He had remained in Ukraine for the past three years to help his mother, who lives alone. He worked at the Odesa port. He admits that as soon as the law in Ukraine has changed, he settled all his affairs and left immediately. Nothing was keeping him in Ukraine anymore. All his friends had left the country back in 2022, some of them for Munich. "I was the last of my friends to stay in Ukraine," Andriy adds.

I talk to Andrii early in the morning but the refugee center has been awake for several hours. Early in the morning, a van covered with the first snow arrives at the back entrance with food — pallets of fresh bread, milk, and other products. The center provides three meals a day for all residents.

I was the last of my friends to stay in Ukraine

In total, almost a hundred people help Ukrainian refugees here: security guards, psychologists, administrative staff, cooks, cleaners, and a doctor. The center also employs about forty volunteers, including Ukrainians, who help refugees with language and integration and organize entertainment events.

Dining hall at the center for Ukrainian refugees in Munich. Photo by the author.

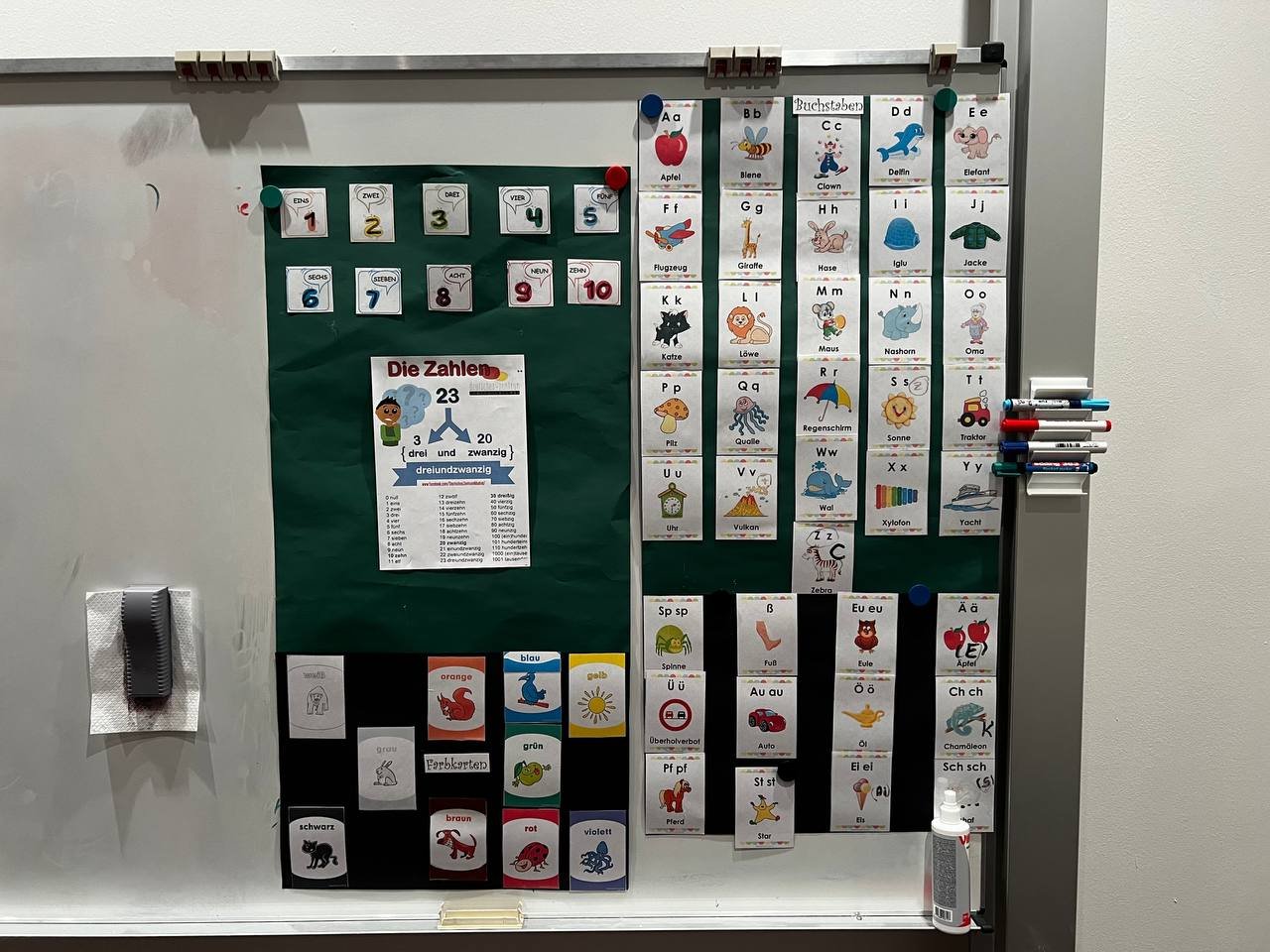

The room where German language courses are held. Photo by the author.

The room where German language courses are held. Photo by the author.

A room with clothes for Ukrainian refugees. Photo by the author.

Laundry room. Photo by the author.

One of the toilets in the center for Ukrainian refugees. Photo by the author.

Medical station. Photo by the author

A food truck near a center for Ukrainian refugees. Photo by the author.

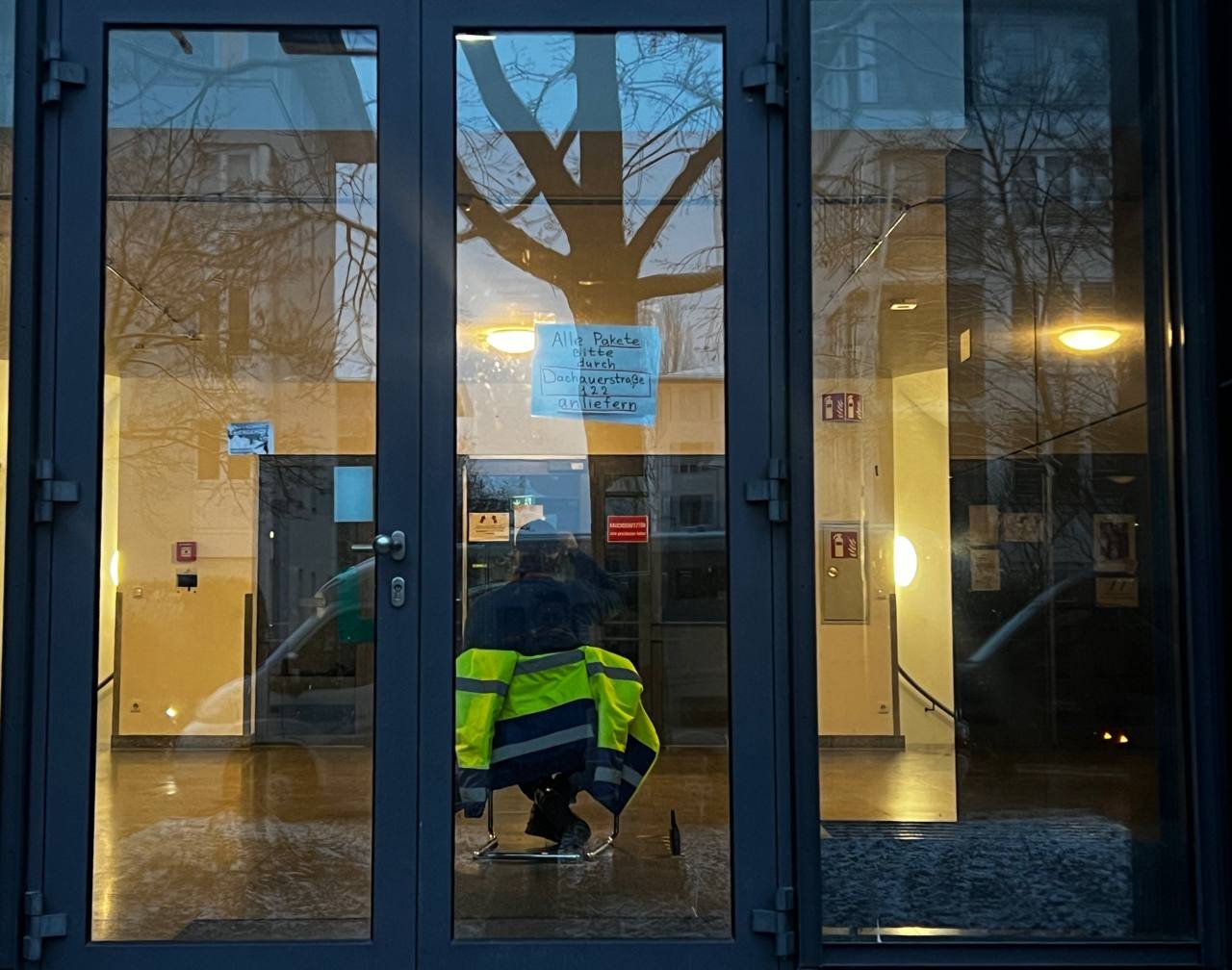

A security guard on duty at the back entrance to the center. Photo by the author.

One of the corridors in the center for Ukrainian refugees. Photo by the author.

The building resembles a city within a city, or rather a society within a society. It has its own rules, its own daily routine, its own problems, and its own joys.

However, it is pretty challenging to get inside this «community». After standing outside in the snow for two hours, the center's director came out to us. He asks for our press cards, photographs, and passports, and tells us to wait for two hours. After several rounds of negotiations, even with the city council, they decided to let us in.

Yulik, 19

As soon as we enter, it becomes clear there are many young people in the center. It isn't easy to count them, but at one point, the dining room is almost filled with young men and women — about two dozen of them. Since August of this year, the number of young men in the center, as in Germany as a whole, has increased significantly.

Ukrainian boys come to Munich in different ways: some alone, some with their parents, sisters, or brothers, and some in groups of 3–5 people. However, the longer you walk around the building, the more you notice that there are a lot of boys here with their girlfriends.

Yulik and Anna arrived from Rohatyn in the Ivano-Frankivsk region five days ago. We met in the same cafeteria after lunch. Shy Anna immediately goes to her room, while her boyfriend agrees to talk.

They are both 19 years old. They met three years ago at work in their hometown. Yulik worked as a sushi chef in a local cafe, and Anya was a barista and waitress.

I ask Yulik why he decided to leave. The answer is simple, but quite common: "Everyone said to leave Ukraine". A few days before the move, several Shahed-drones attacked the Rohatyn community. This was the deciding factor for Yulik's family.

However, at first, Yulik did not want to move, so her parents decided to send the boy alone. When the family accompanied the young man to the bus to Munich for the first time, Anna could not hold back her tears. The boy did not get on the bus — Anna said, «I'll leave with you!»

A week later, they left for Germany together. After a forty-hour journey, the couple arrived at the train station in the central city of Bavaria, where Yulik's cousin picked them up. After spending the night at his brother's apartment, the young people registered at the center. They are currently waiting for their documents and want to start working right away.

Yulik's cousin has already found him a job near Munich delivering mail. However, Yulik wants to work with Anya, at least at first.

"We'll look for work. Why should we be a burden on someone else?" says the young man. Yulik hasn't thought about education yet, but he wants to learn languages.

"I had German in school, but I didn't study it. The teacher said, 'Learn German, because it will come in handy someday,' but I didn't feel like it".

The young man is finding it a little tricky to adapt to the country and the city. He admits that he never liked Germany, and he still doesn't like it very much. Munich is too big: "You go out into the city, and there are crowds of people everywhere. Everyone walks around as they please and knocks you over:". He felt much more comfortable in Rohatyn. You go out, you know everyone, and you greet everyone.

Yulik and Anna live in one room. They openly complain about the previous tenants: "Couldn't they have just wiped those windows with a rag?" In just a few days in Munich, they have already done a thorough cleaning of their new home, washed the windows, and bought necessities.

"If anything, we bought a blanket! It wasn't there before," Yulik notes as I photograph the room.

Yulik and Anna want to return to Ukraine in the future, but they are not making any plans yet.

German Christmas stollen

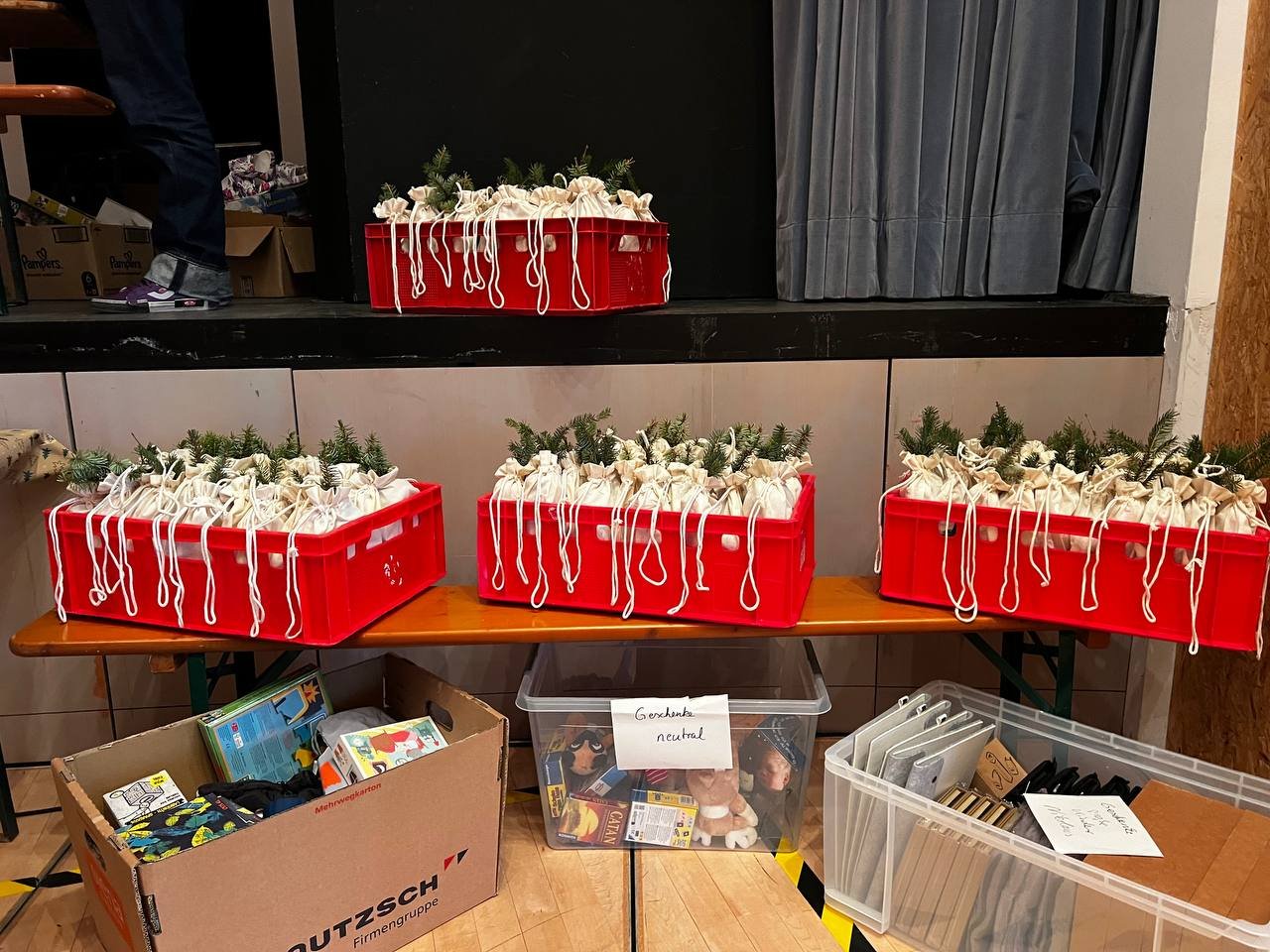

While we chat in the dining room, meticulous preparations for the winter holidays are underway in the same building. Every year, the administration holds four large-scale events for residents in addition to the regular program of board games and Mafia nights.

Several Germans are working in the large hall. Smiling, they bring in boxes of gifts for children and adults, lay out stollen (traditional German Christmas pastries) on the tables, and arrange the benches.

Hall in the center for Ukrainian refugees. Photo by the author

Hall in the center for Ukrainian refugees. Photo by the author

Gifts for Ukrainian children. Photo by the author

Holiday gifts for girls. Photo by the author

Andrii, 20

In a few hours, another young man, also 20-year-old Andrii, will sing a traditional German Christmas song in this hall. His two younger brothers, aged 9 and 13, will help him.

After the full-scale invasion began, the young man divided his time between Kyiv and Ivano-Frankivsk. He enjoys programming (which he learned at the University in Ukraine) and drawing. Andriy says, "I can draw anything you want".

His family took the move very seriously. They had been planning to move together for a long time, but couldn't because of the boy's age. As soon as the law allowing Andrii to leave the country came into effect, the family set off for Munich.

The boy dreams of working as a programmer. He does not want to return to Ukraine. There are more opportunities for him in Germany. While their father is in Ukraine, Andrii helps his mother with his younger brothers. At the celebration, they sing together and collect gifts together.

While the Ukrainian children are receiving their gifts, two women sit down next to me. One quickly calls her sixteen-year-old son: "Dima, hurry up, we need to get your gift!" A young couple, Vova and Natasha, approaches the other woman. Upon learning the boy's age, she exclaims joyfully, "My goodness! Well done for leaving!"

Vova, 21

Vova, 21, from the Dnipro region, left Ukraine less than a month ago. He had already started studying at university in his homeland. He will finish his studies in Germany, remotely.

When the opportunity arose for young Ukrainians to leave, Vova's girlfriend, Natasha, came to pick him up. She is 22 years old, has been in Munich since the start of the full-scale war, and has been at this center for several months. At first, they were a little awkward during the conversation, especially when they found out that I was a journalist. However, socialization in such conditions happens quickly. Half an hour later, we were already discussing each other's drunken adventures.

The couple has no plans to return. Natasha has already confirmed her A2 level of German and is preparing for B1. For them, Germany is much more promising for work and salaries. «When I went to pick up Vova, I stayed in Ukraine for four months. It's like heaven and earth compared to Germany,» says the girl.

While I go to take a photo of Yulik and Ani's room, the couple returns with gifts they won in a win-win lottery: a thermos, a blanket, and a funny pink bag. Vova and I take turns holding the bag and joke that integration into Europe is happening very quickly.

Vova and Natasha are full of optimism. They like the center — there is always something fun going on. As we stand and talk about this, a man pushes a small wheelbarrow, and a center employee stands on it, laughing.

We all laugh together.

After the main celebration, the administration invited the three of us to a performance by an international choir that was specially invited to the event for Ukrainian refugees.

About three dozen Ukrainians and several Germans, whom we saw during the preparations for the celebration, gathered in the dining room. To the familiar tunes of "Jingle Bells" and Paul McCartney's "There is no Heaven," Vova jokes loudly, and Natasha scolds him: «Why do you start talking so loudly when everyone else is quiet?»

Behind us, a couple argues, several children run in front of the singers, an older woman in front of us wipes her eyes, and Vova holds Natasha's hand.

The festive choir sings Paul McCartney's “There is no Heaven.” Photo by the author.

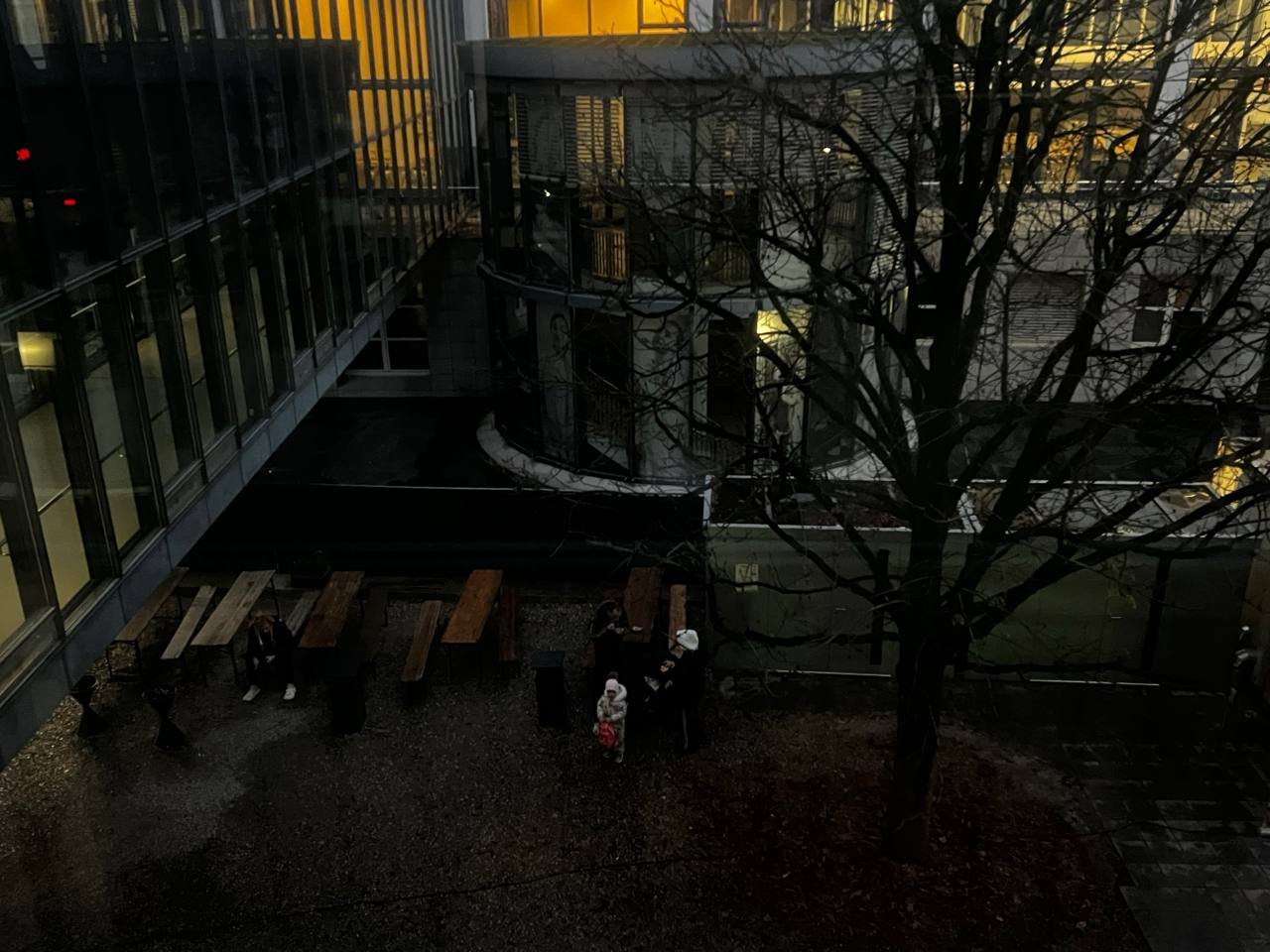

Ukrainians in the courtyard of a center for Ukrainian refugees. Photo by the author.

They all have one thing in common: they chose a life of safety, despite everything they will have to go through in the future. However, there is a constant feeling in the air that this safety and happiness remain too fragile.

Three weeks ago, due to the large number of newly arrived young Ukrainians, the German chancellor called President Zelensky and asked him to stop the torrent of young people from Ukraine.

«They are needed there, in Ukraine,» Merz said.