Sustainable war. How Ukraine can defend its northern border with peatlands

A resident of Makariv district once told Texty.org.ua about the movement of an occupying column in northern Kyiv region: "The Russians drove straight out of the forest, which used to be entirely peatlands. However, during the Soviet era, melioration efforts created a road, and that's the route they took."

While there are no active hostilities on Ukraine's northern border currently, a potential attack from Belarus remains a constant threat. As a Russian satellite, Belarus has served as a launchpad for previous attacks, and Chernihiv region is also under constant threat. This necessitates maintaining troops and constructing fortifications along the northern border. However, Ukraine possesses a natural barrier in its north: peatlands.

These peatlands were once nearly impassable, though many areas were drained during the Soviet era. Restoring this natural barrier is crucial.

The entire northern part of Ukraine is part of the Polissia region, renowned for its peat bogs.

In its natural state, and without prolonged frosts, peatlands present an insurmountable obstacle for both wheeled and tracked vehicles, which simply cannot navigate the mire and surface water. Only hovercrafts, typically used in maritime operations and thus far from Polissia's mires, can traverse such terrain.

Despite this, the Russians did prepare for a northern offensive and explored local routes, including those through the peatlands. In 2021, Ukrainian General Viktor Muzhenko warned, "Russian troops have already practically studied all the conditions and terrain — the Pinsk (i.e., Pripyat) peatlands and Polissia.

This is a potential danger to Ukraine." Their reconnaissance makes sense, as the attack began in February. Before climate change, February brought maximum freezing of the peatlands, allowing tanks to cross. (Texty.org.ua has previously reported on how soil passability impacts equipment advancement.)

The Russian offensive in northern Ukraine was facilitated by the extensive drainage of mires, a result of Soviet-era land melioration efforts following World War II. For instance, the Russian advance through the Chornobyl Radiation and Ecological Biosphere Reserve was made easier because all its wetlands had been drained either before or immediately after the 1986 accident. Military equipment moved easily across these drained areas, stirring up clouds of dust formed from peat degradation. This radioactive dust from the drained peat bogs temporarily increased radiation levels near the Chornobyl station by 20 times.

The threat remains

While the threat of an offensive from the north, particularly from Belarus, is often discussed as hypothetical today, historical evidence indicates that preparations for such a scenario were underway long before 2022. Potential offensive routes could extend beyond the Chornobyl zone, and this threat persists even now.

In 2015, Belarus began constructing military roads on the Olmany-Perebrody mires, which are the largest undrained pristine peatland area in Europe and straddle the Ukrainian-Belarusian border. Previously, roads in this area existed only on the Ukrainian side. Within a few years, Belarus built over 100 km of roads, including a defensive line and a road leading to the Olmany border post, adjacent to Perebrody village in Rivne Oblast. The Ukrainian cities of Zhytomyr and Novohrad-Volynskyi are located in close proximity to this border.

It is notable that all roads from Belarus lead to the border and are "coordinated" with Ukraine's road network. Had there been no roads on the Ukrainian side and only natural peatlands, constructing roads in Belarus might not have been strategically logical. In peacetime, roads are beneficial for trade and travel. However, a lasting peace with this neighbour is not anticipated in the coming years.

Fortifying with Peatlands

The European Union, for example, is considering establishing a special fund of €250-500 million to finance measures supporting strategic defence areas comprising peatlands.

Discussions about the necessity of restoring peatlands as a defensive line are actively taking place among Ukraine's Western allies, whose territories also feature peatlands. This topic is being debated in Poland, and German researchers are publishing on it.

This is not surprising, given that the Alliance, with Finland's recent accession, now shares a surprisingly long border with a potential adversary, Russia. Crucially, in many places, especially in the north, this border runs through existing or former peatlands. Historically, border peatlands have always reduced the number of personnel required for defence.

Mires can also pose a significant obstacle for modern equipment, as tragically demonstrated during a recent NATO exercise in Lithuania where four American soldiers died when their tracked vehicle became submerged in a local bog.

However, the idea of creating a "peatland" demarcation line is not solely a military concern. Environmentalists are also actively engaged in this discussion. This convergence of interests is significant, as substantial defence funds could simultaneously serve to protect climate and nature, while also preserving water resources

Replenishing Water Levels

The passability of peatlands is directly dependent on their water levels, which are declining in Polissia due to land drainage efforts, climate change, and increasingly, amber mining.

Out of an estimated total peatland area of 2.2 million hectares over 1.2 million hectares have been drained during the Soviet era

Out of an estimated total peatlands area of 2.2 million hectares (as of 1959) in Ukraine, over 1.2 million hectares have been drained during the Soviet era. The extent to which these have been completely destroyed by peat extraction remains unknown. Considering that every large mire in Ukraine now incorporates a drainage system, the actual number of drained peatlands is significantly higher. Currently, there are no protected area in Ukraine with completely pristine (non-drained) mire areas.

Consequently, the proportion of mires has sharply declined, a trend further exacerbated by climate change.

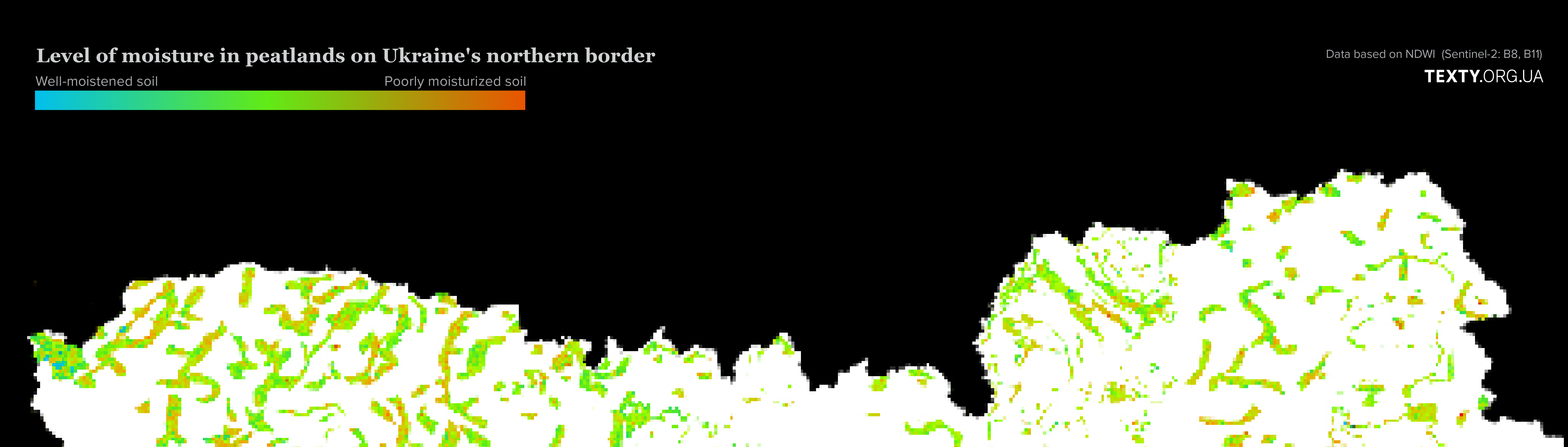

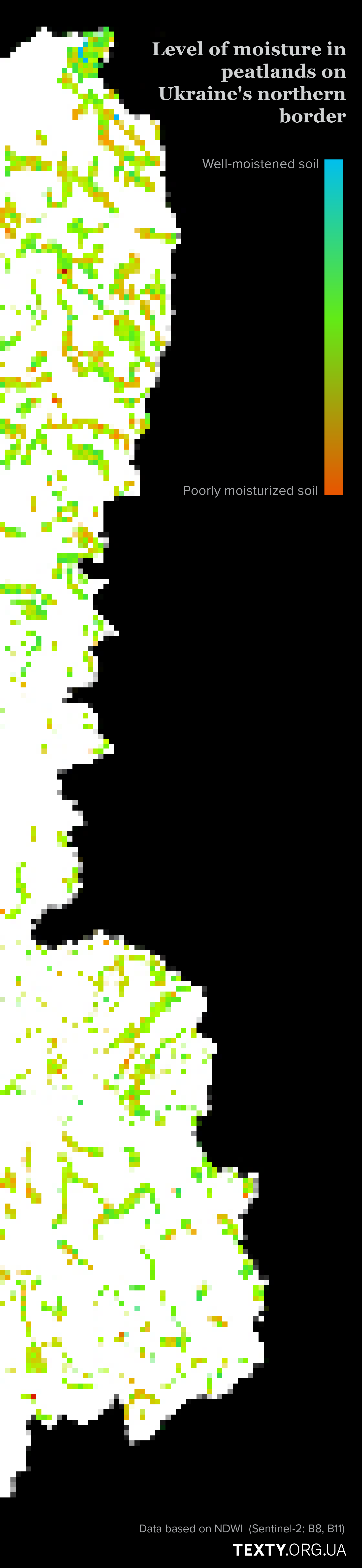

The prevalence of yellow and light green on the map indicates that most of the former bogs are now dry. This is primarily because the drainage channels, even in a state of disrepair, continue to divert water from the marshes.

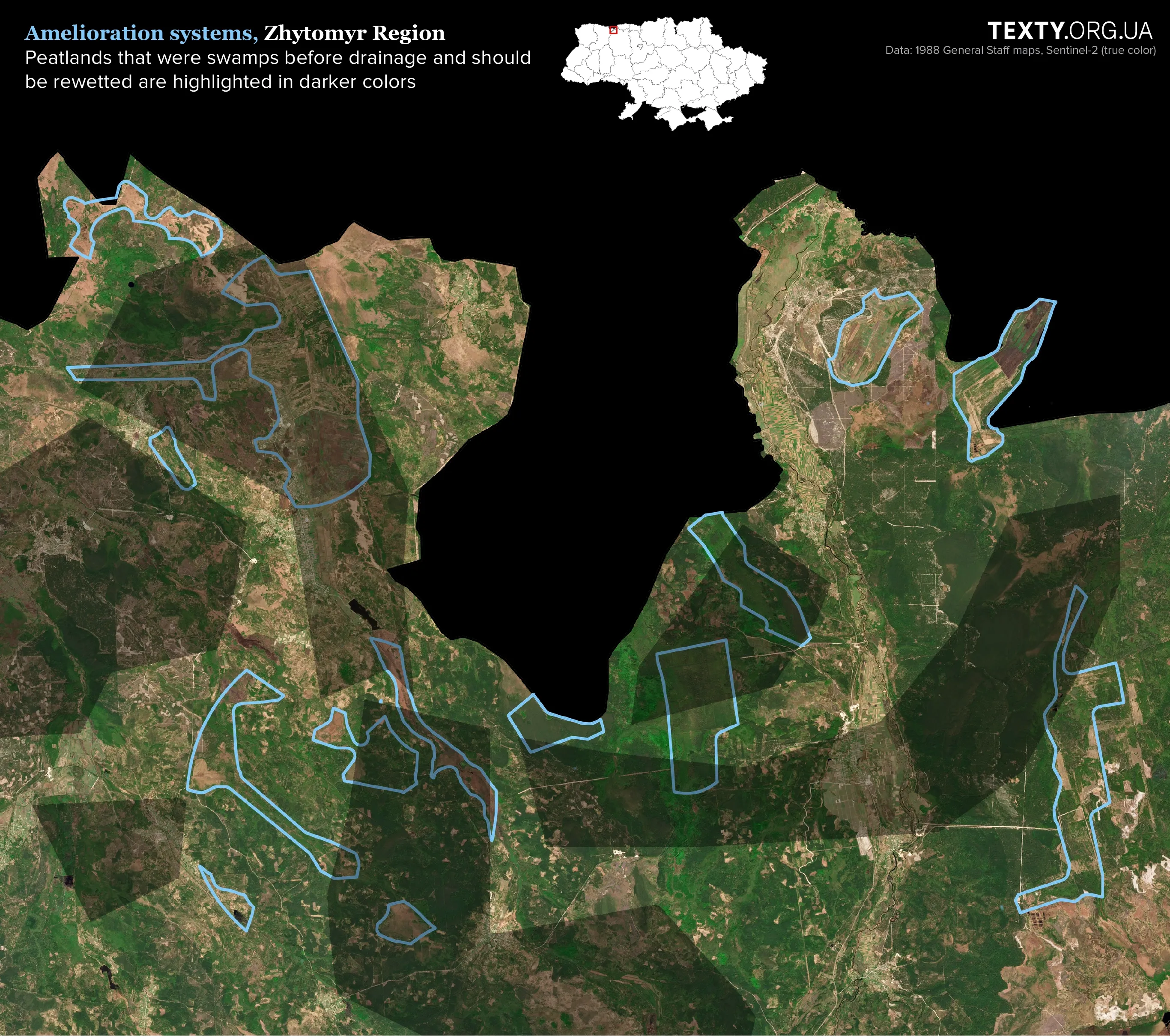

Let's examine a section of the border and its associated peatlands more closely.

Peatlands drainage efforts peaked between the 1960s and 1980s. This means that drainage facilities in Ukraine can still direct water towards Belarusian territory. Water is a valuable resource, and we are, in essence, freely providing it to a hostile state.

The systems marked in blue are responsible for draining the peatlands. The water removed through these canals ultimately flows into the Pripyat River, specifically the section located within Belarus. This process leads to the drying of our peatlands, increasing the vulnerability of Ukrainian territory, and effectively transferring a valuable resource to a hostile nation. If these drainage systems were to be "closed," the water level would rise, making Ukrainian territories less passable for the aggressor's military equipment, while retaining this valuable resource within our borders.

The scarcity of water is further aggravated by environmental issues stemming from amber mining. This technology involves draining the peatlands, removing layers of peat and sand, and establishing a quarry.

Furthermore, peat extraction is a regular occurrence, not only in established deposits but also, at least until a few years ago, in newly developed ones.

This practice must cease. We cannot simultaneously endeavor to restore peatlands as a defensive barrier against Russian forces while continuing to drain them and extract peat

Restoring Peatlands: Methods and Challenges

Ukraine has already made its first attempt to restore a peatland ecosystem in the Roztochya nature reserve in the Lviv oblast. This involved laying pipes in the upper part of the bog to divert water from a nearby river. The water was then distributed across the area using a system of newly laid or cleared old ditches, which historically served the opposite purpose of drainage. Additionally, one of the central reclamation canals was fitted with an overflow dam to raise the overall water level throughout the peatland. (You can read more about this specific project here.)

Some experts argue that in the process of natural recovery, installing new canals and pipes can actually harm the peatland. Nevertheless, this existing experience offers valuable insights that should be considered for future efforts.

Learning from Nature: The Beaver Approach

For widespread peatlands rewetting, simpler and more cost-effective defence solutions should be explored. We can draw inspiration from the original "engineers" of wetlands engineers: beavers. The dams they construct require no special expenses, as all materials are readily available in their environment.

Mimicking beaver dams—by creating structures from wood, clay, and similar natural materials—could be a highly effective and economical strategy for re-wetting these crucial ecosystems.

While such structures are not inherently permanent, with proper construction and consistent maintenance, they effectively serve their purpose. Furthermore, there's a high probability that rising water levels will attract real beavers, guaranteeing the long-term success of any rewetting project.

Alternatively, fixed wooden barriers can be constructed, or existing channels can even be blocked with peat. A combination of these approaches is also feasible. Numerous technical solutions exist, adaptable to various budgets and terrains. Moreover, many European organizations and experts are available to provide free advice and professional guidance on peatland restoration and rewetting in Ukraine.

There are numerous technical solutions for any budget and any territory

Відновлення торфових боліт передбачає відновлення екосистеми, яка існувала до осушення. І це не так просто, щоб відбуватися без професійної експертизи, якої в Україні наразі не існує, але й не так складно, щоб українські фахівці не змогли цього навчитися.

Peatland restoration entails re-establishing the ecosystem that existed prior to drainage. While this process is complex enough to require professional expertise—which is currently lacking in Ukraine — it is not so daunting that Ukrainian specialists cannot acquire the necessary knowledge.

In contrast to peatland restoration, rewetting focuses on raising the water level (ideally, the higher, the better). This approach allows for the creation of new wetlands or the cultivation of plants tolerant to high water levels in these areas. Rewetting is a significantly more costeffective option and offers potential economic benefits. However, constant monitoring of water levels is crucial in all cases to assess the peatland's passability for military vehicles.

Cost needed

Given the scale of the undertaking, it is unrealistic to expect to transform most of the border into waterlogged peatlands at minimal cost. This is also because after years of drainage, some areas simply lack sufficient water.

The cost of rewetting of one hectare of Ukrainian drained peatlands can range from €300 to €1500. This price variation is influenced by factors such as material costs (as noted, scrap materials or engineered structures can be used), the peatland's location and size, the availability of technical documentation for the drainage system, the condition of hydraulic structures, monitoring requirements, the specific goals of restoration or rewetting, and the accessibility for equipment.

Complete rewetting typically requires 2–4 years, depending on water inflow. Even with these considerations, restoring marshes is more cost-effective than constructing extensive concrete fortifications and continually digging and maintaining trenches, which are often flooded in this region. Furthermore, fewer soldiers would be needed to defend areas protected by rewetted peatlands.

Fortunately, a substantial amount of land in Ukraine remains under communal ownership, unlike in the EU where most land is privately owned. This simplifies the process of allocating land for peatland restoration.

Additionally, a law currently in force during martial law extends the border zone with Belarus and Russia to 2 km.

Within this zone, the military can change the designated purpose of state and communal land for the construction of engineering and fortification structures, and can seize agricultural land along the state border. This provides an opportunity to restore peatlandsin the two-kilometer zone near the border, should they choose to do so.

Economic Benefits of Peatland Restoration

It is important to remember that peatland restoration is now recognized as a tool for reducing CO2 emissions. A carbon market is already active and developing, where, after peatlands have been rewetted, regular payments can be received simply for their existence.

Regular payments can be received simply for the peatland's existence

However, this is contingent on the peatland meeting specific criteria within existing CO2 emission reduction methodologies. Key conditions include the absence of trees, good peat condition (i.e., not completely decomposed), a thickness exceeding half a meter, and the presence of a nearby water source.

Further details on the CO2 emissions trading market can be found here. In such cases, companies are often eager to finance rewetting projects and make annual payments following their own site assessments. The German Michael Succow Foundation offers free advice on this matter.

Ukraine is also among the world's top ten cranberry exporters. Significantly, all Ukrainian cranberries are wild berries sold as organic, consistently commanding a higher price. These cranberries naturally thrive in peatlands.

The Soviet-era drainage of the peatlands in Ukrainian Polissya has contributed to Ukraine becoming a water-stressed country. Consequently, Polissya can no longer fully serve its role as a natural defence barrier. The drained peatlands are prone to burning, which pollutes the air and negatively impacts the health of Ukrainians. To impede attacks from the north, and in light of climate change and the need for water, our peatlands must be rewetted, both today and in the future!

This material was prepared by Texty.org.ua in cooperation with Olga Denyshchyk, project coordinator of the Succow Foundation (Germany).

Attempts to develop Polissia's peatlands with the prospect of turning them into a line of defence date back to the Russian Empire. It was then that they began to design and build drainage systems, some of which were designed to be flooded and stop the enemy. This is a copy of the strategic flooding method that has been used for centuries in countries such as Belgium and the Netherlands.

The experience of military operations in Polissia during the First and Second World Wars shows that peatlands can become an insurmountable obstacle when there is water, and at the same time open a direct path for an offensive in winter when they freeze. But today, with climate change, this is happening less and less.

But let's go back to history. Austro-Hungarian and German troops literally got stuck in the Polissya peatlands during the First World War. The Russian army took advantage of the strategic flooding: it blocked the reclamation canals and flooded part of the drained territory.

Карта Брусиловського наступу. Стрілками показано, зокрема, і наступ росіян через поліські болота

During the Brusilov Offensive of 1916, the defences of Austro-Hungarian and German troops in the same region were breached. This offensive was launched in the summer when water levels in Polissya were at their lowest.

After the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth gained control of the region in the interwar period, the Poles attempted to transform the peatlands into a defensive line, this time against the Soviet Union.

A significant number of hydraulic structures, along with actual firing points, were built on the Sluch River, intended for military defence. Specifically, plans were made to block the flow of the Sluch River upstream from Sarny with two locks and redirect the water through canals towards the marshy lowlands. This would have created an impassable line against an eastern offensive. However, this defence was never utilized due to the overall collapse of the broader defensive strategy.

Russians Account for Northern Peatlands

The Russians possess considerable experience in conducting military operations in peatlands. Research into constructing paths for military equipment through peatlands has been ongoing since World War II. In the Soviet Union, it was common for peatland scientists to teach at military academies or conduct research for the Ministry of Defence.