War on Pedestals: How monuments serve propaganda in modern Russia

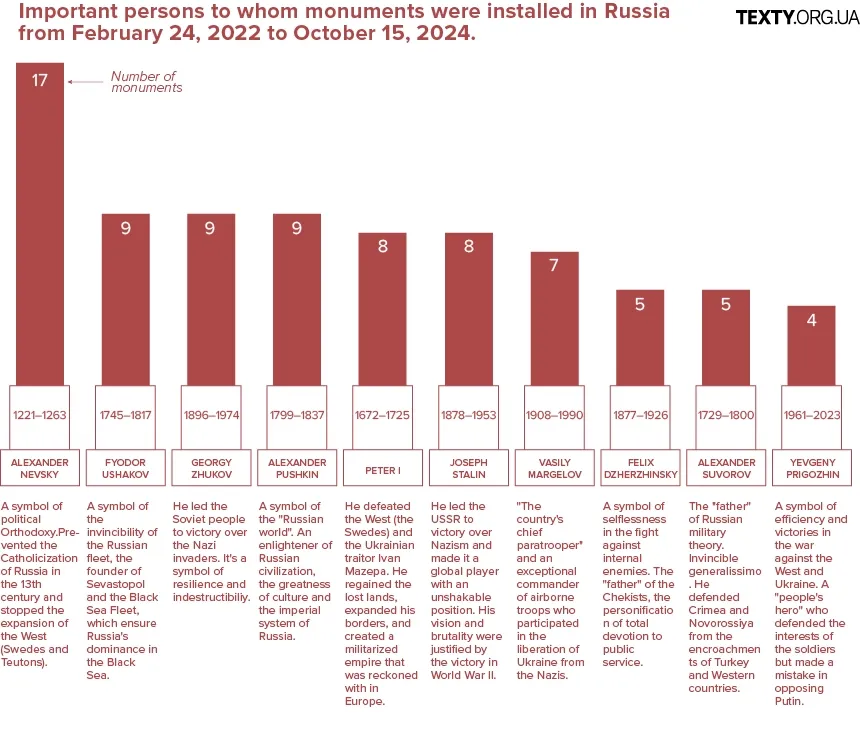

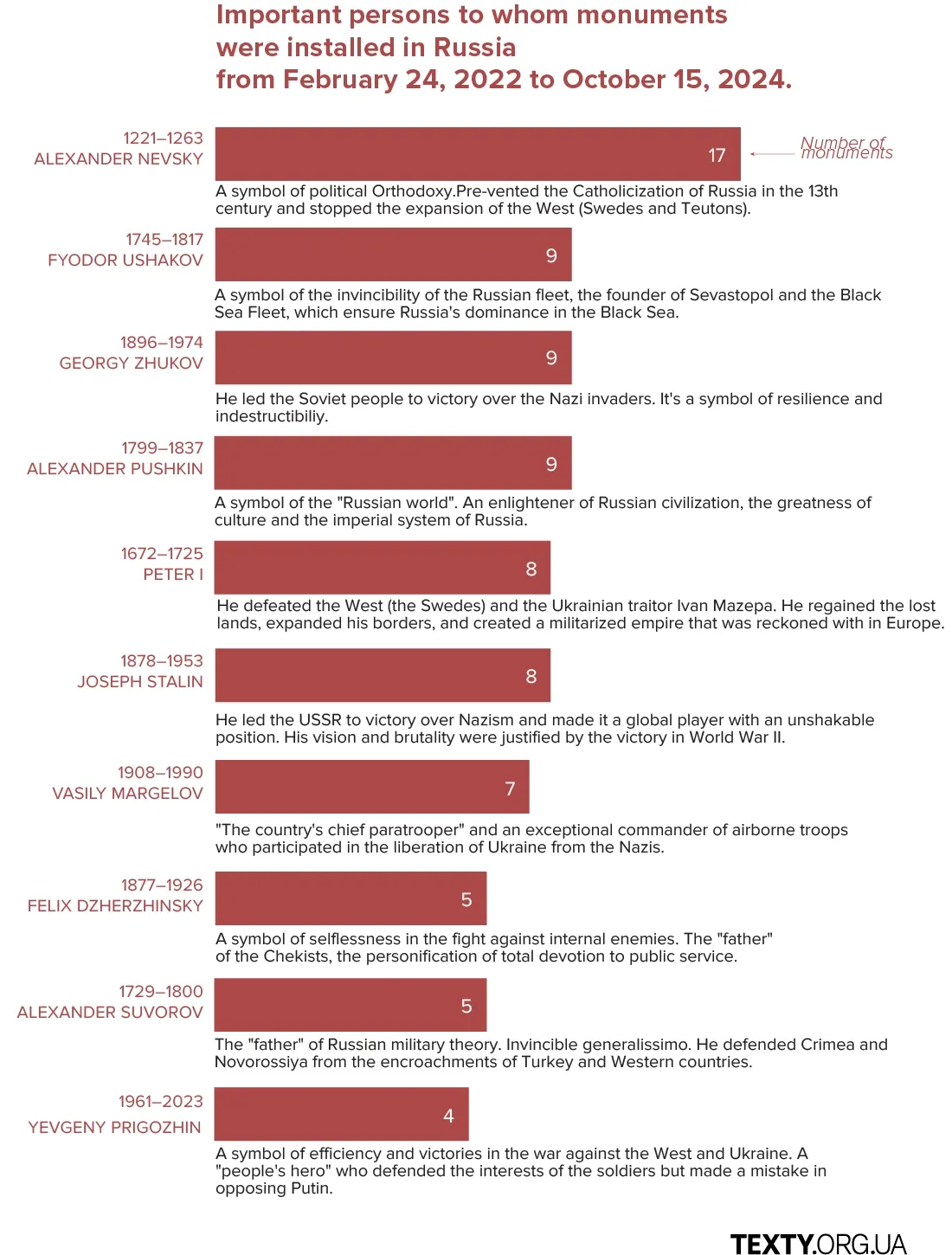

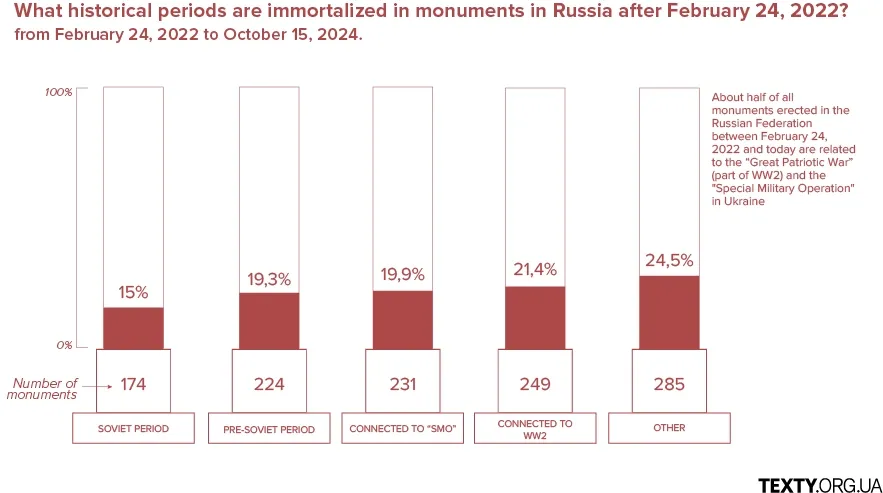

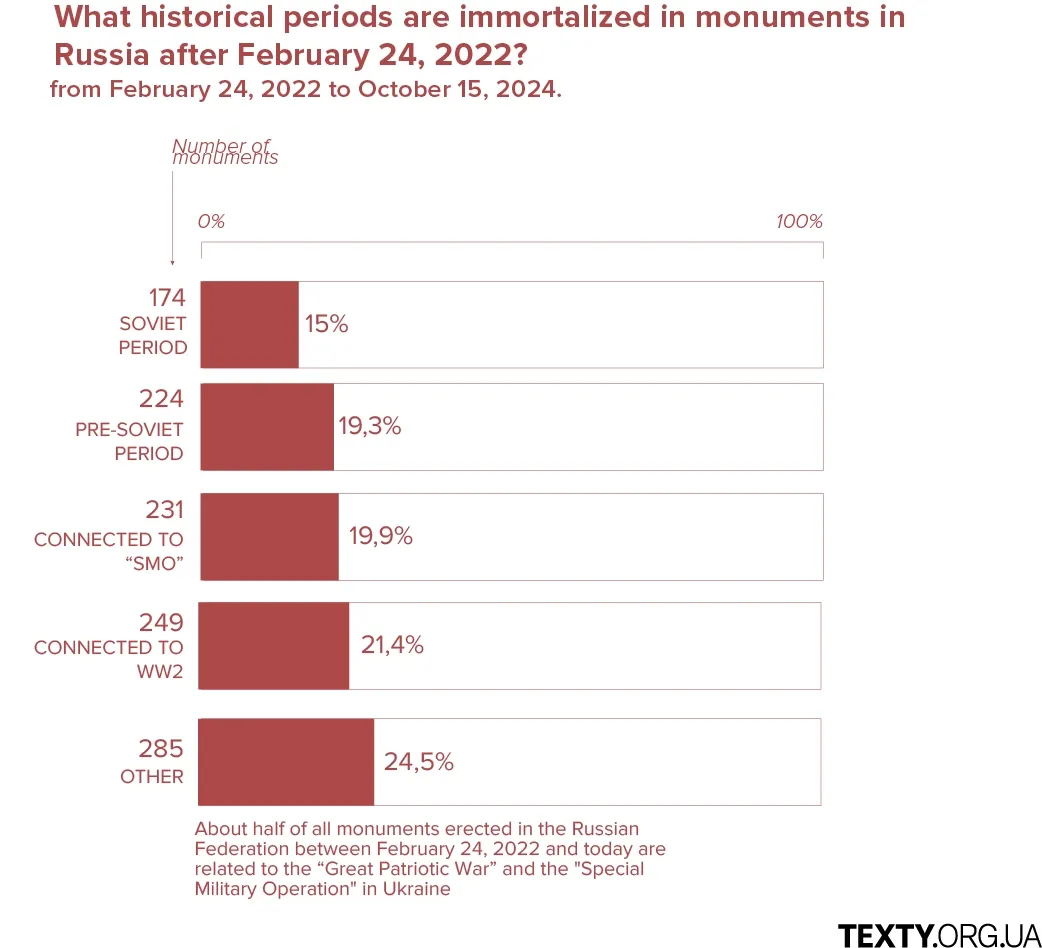

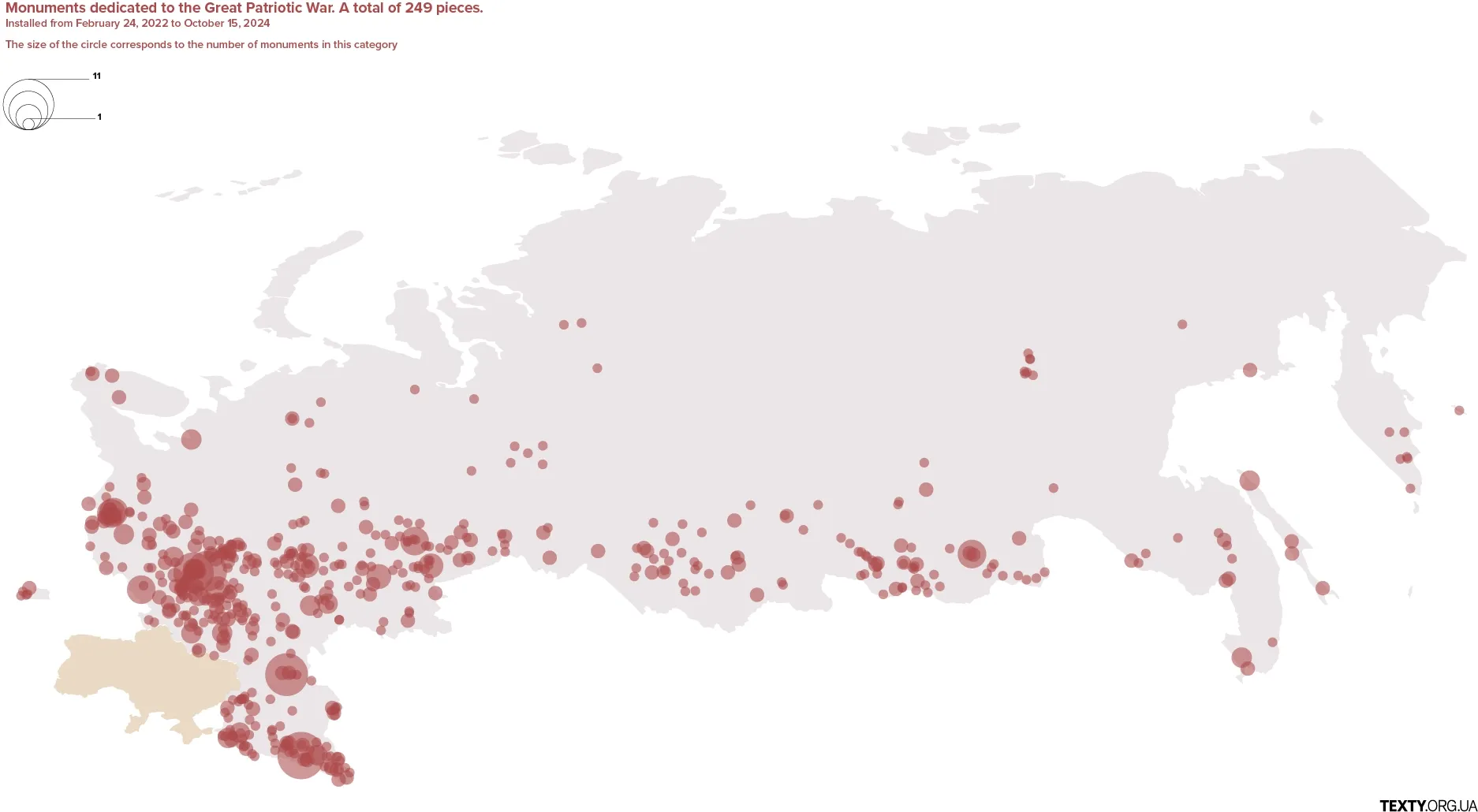

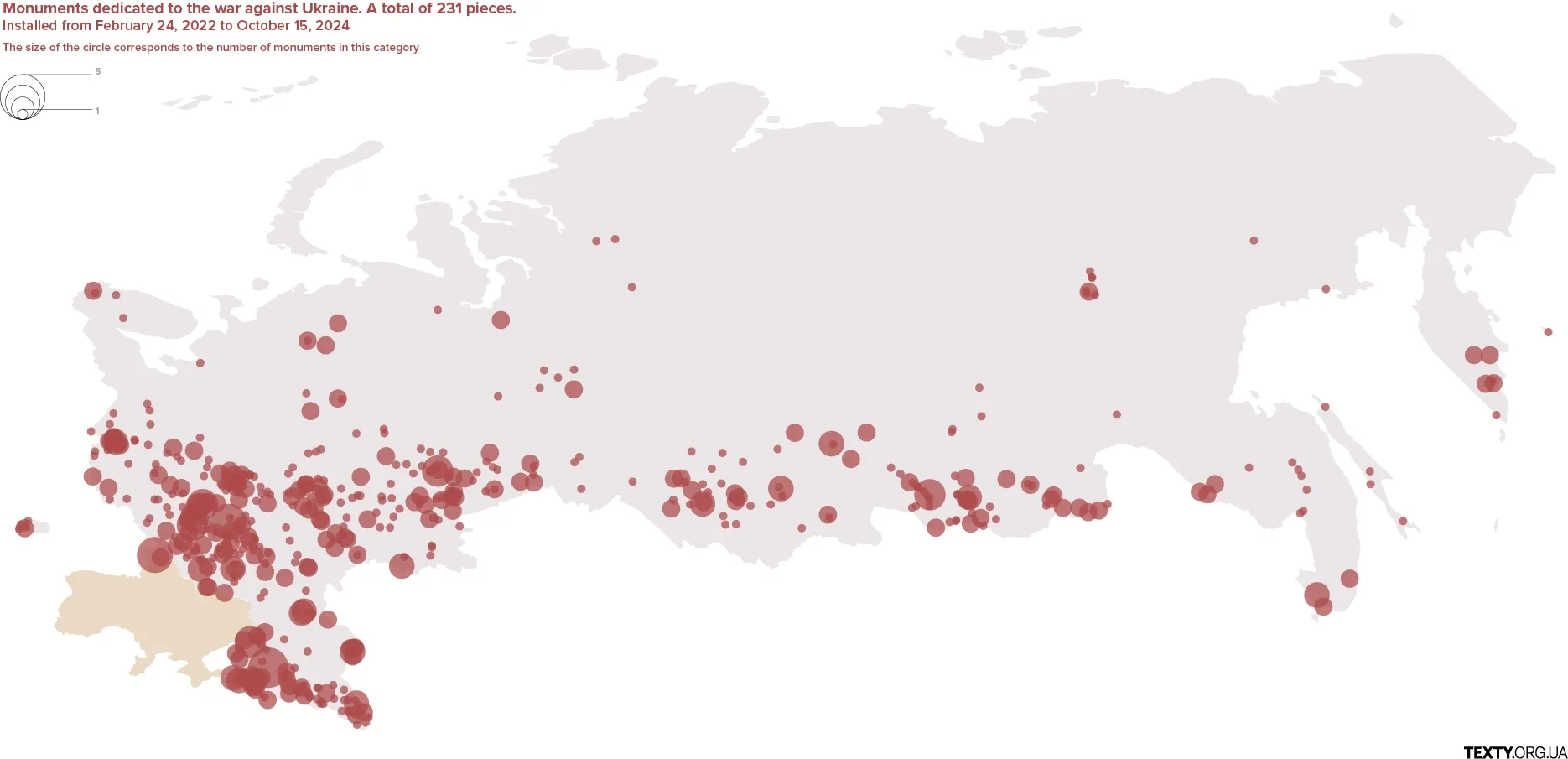

What monuments are installed in modern Russia? Texty.org.ua has identified 1163 monuments constructed and opened in Russia during the full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Almost half of them are dedicated to wars: World War II or the invasion of Ukraine.

Monuments symbolizing the eternal struggle against the "collective West" are also being actively built in Russia.

War on

Pedestals

How monuments serve propaganda in modern Russia

What monuments are installed in modern Russia? Texty.org.ua has identified 1163 monuments constructed and opened in Russia during the full-scale invasion of Ukraine. Almost half of them are dedicated to wars: World War II or the invasion of Ukraine.

Monuments symbolizing the eternal struggle against the "collective West" are also being actively built in Russia.

Monuments against the West

In its domestic propaganda, Russia constantly repeats that it isn't at war with Ukraine, but with the West. This is also reflected in the monuments. We have found a whole class of monuments that glorify events and heroes who, according to the official version, resisted Western aggression and defended Russia's national interests.

Assessing the symbolic significance of these monuments and the narratives that are spread about the immortalized figures, one can see that the idea of Russia as a "punisher" of the West is being promoted — a country that not only defeated but also "punished" Europe for its ambitions and attempts to encroach on Russian interests.

For example, the restoration of the monument to Kuzma Minin and Dmitry Pozharsky in Moscow and the construction of a monument to Patriarch Hermogenes in Nizhny Novgorod remind Russians of how they survived the Time of Troubles in the early seventeenth century in wars with the Poles and Swedes.

In 2023, the authorities of the Kaliningrad region of Russia opened a monument to General Mikhail Muravyov. Muravyov is in no way connected to the history of Königsberg and East Prussia (modern city of Kaliningrad and the region). He is known for brutally suppressing the Polish uprising in the Russian Empire in 1863, for which he was nicknamed "the Hanger."

And the installation of monuments to Soviet spies in Britain Kim Philby (Belgorod) and Rudolf Abel (Samara) refer to the successful stories of the Cold War.

The targeted construction of such monuments right now can be seen as shaping the perception of Russia as an eternal winner in conflicts with the West.

By building monuments, Russia is also trying to scare. In September 2022, a monument to a T-34 tank was put in the city of Ivangorod on the border with Estonia. Just a hundred meters across the Narva River is the city of Narva, where there used to be a similar monument, but the Estonians removed it. The muzzle on the memorial looks toward Estonian city, which Russians consider their own and is home to a significant Russian ethnic minority.

In the Krasnoyarsk region, a monument to the powerful Sarmat nuclear missile with the caption "Silence After Us" was built. Inventors of nuclear weapons, tanks, artillery, and uranium researchers receive their copies in granite and bronze.

And to show that Russians aren't afraid of sanctions, a monument to a rabbit with a ruble crushing the dollar and euro was unveiled in Lipetsk.

"Traditional" values

In modern Russia, monuments are also massively constructed to emphasize traditional values.

For example, monuments are erected to St. Peter and St. Fevronia, representing marital fidelity and love. There are about a hundred monuments to these characters in Russia, eight of which have appeared in the last two years.

Another important element is religion. Despite the large Muslim population and several other religious minorities, Russia positions itself as an Orthodox country, and monuments to Orthodox saints emphasize this. The construction of such monuments sends a signal that Russia remains a stronghold of spirituality and conservative values in a world that the Kremlin believes is moving away from its roots.

Other religions monuments aren't built with a great willing in Russia. And when they are constructed, it's an act in an ideological war with the West. For example, the monument to the Quran in the city of Miass (Chelyabinsk region) was unveiled in response to the burning of the Quran by an extremist in Sweden, not because of love for Islam in Russia. This is a slap in the face to the West, which allegedly burns the holy books of other religions while Russia allegedly preserves them.

The figure of Pyotr Stolypin (two new monuments that were unveiled during the study period) symbolizes stability and state governance, while Gavrila Derzhavin's (three new monuments) embodies the ideas of a strong state and conservative ideology.

Liberals are left out — it's a time when only supporters of hard-line state policies and defenders of "eternal values" are recognized.

Russian monuments are turning into a tool for promoting the idea that the country is based on traditionalism, Orthodoxy, and statehood, and the author of the formula "Orthodoxy, Autocracy, Nationality," Sergey Uvarov, is being honored with a monument in St. Petersburg.

Colonial policy

New monuments in regions with primarily non-Russian populations have a purely colonial message and emphasize Russia's role as an "enlightener" of the peoples it conquered, then tortured and assimilated.

Monuments to enlighteners of the Yakuts, Khakass, and other small peoples are being built to remind us how Russia "civilized" these territories.

Nationalist and pro-fascist organizations receive state assistance in constructing monuments to important figures. That's why they put up, for example, a bust of Ivan the Terrible in Astrakhan. This Russian ruler seized the Astrakhan Khanate in the 16th century, destroyed the city, and slaughtered the local population. The mention of this should have outraged modern Astrakhans. Still, the bust of Ivan the Terrible is presented as evidence not of the forced annexation of Astrakhan but of the principality's accession to a strong, civilized, and cultural state.

The cult of war

The largest group of new monuments is dedicated to the "Great Patriotic War" and the so-called "Special Military Operation" against Ukraine.

These periods have become key components of state propaganda, which constructs the historical memory of Russians so that the current Russian-Ukrainian war seems justified, and history emphasizes the exclusivity of Russia's civilizational mission.

For Russians, all Ukrainians are Nazis. Much has been written about why and how Russian propaganda hammered this thesis into the minds of compatriots long before the invasion in 2014.

This policy is also reflected in monuments. The pace of building and reconstruction of memorials to the "Great Patriotic War” has been accelerating significantly since the full-scale invasion, even though almost 80 years have passed since the end of World War II. Sometimes, it gets to the point of absurdity when old monuments are erected in some cities, left over from the renovation of memorials in others; read about such a ridiculous example here.

By constructing monuments dedicated to the "Great Patriotic War," the Russian authorities create a messianic image of a nation that is called upon to save the world from new threats.

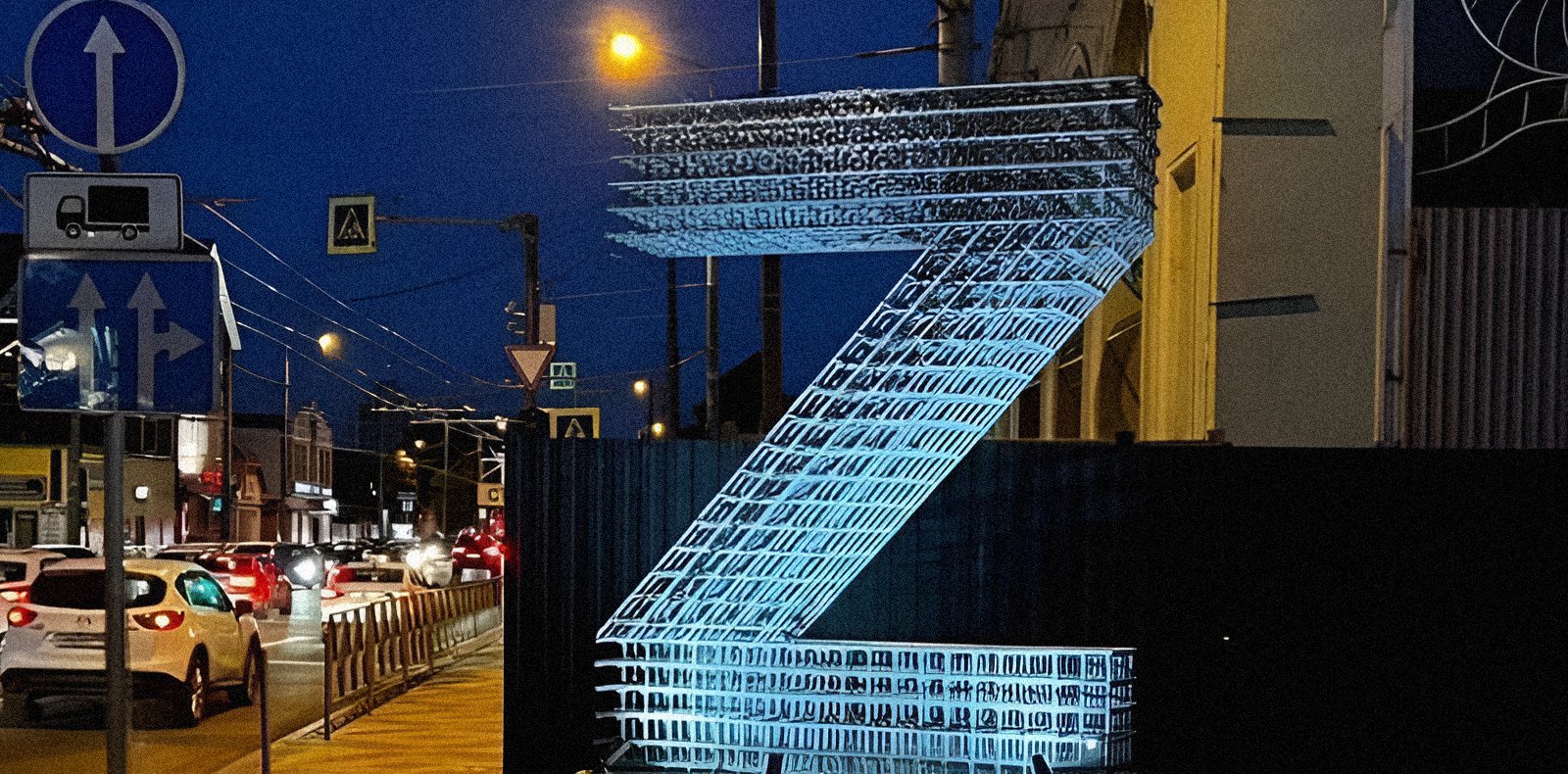

"Z", "V" and an old woman with a flag

The obsession with victories resulted in a new war, and thus in new monuments. It's interesting to trace the changes in their subjects.

Initially, these were monuments with the letters "Z" and "V". Then came a wave of monuments to "grandmothers with a red flag."

"Grandma with the Flag" is a Ukrainian woman, Hanna Ivanova, who, in 2022 in the Kharkiv region, came out to Ukrainian soldiers with a Soviet flag, confusing them with Russian flags. Russian propaganda made her a symbol of "opposition to fascism."

After the woman explained her motives and said she wasn't opposing the Ukrainian government, new monuments to the "grandmother with the flag" stopped appearing.

Support TEXTY.org.ua

TEXTY.ORG.UA is an independent media without intrusive ads and puff pieces. We need your support to continue our work.

New "heroes"

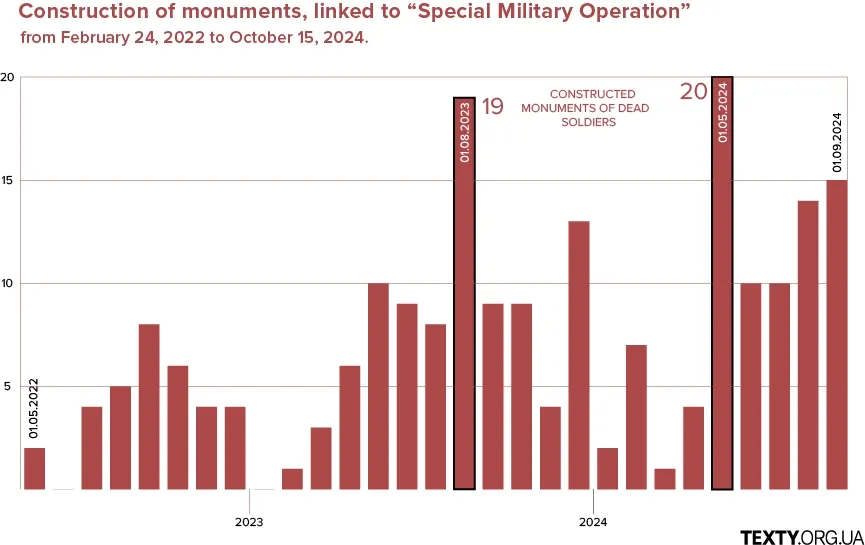

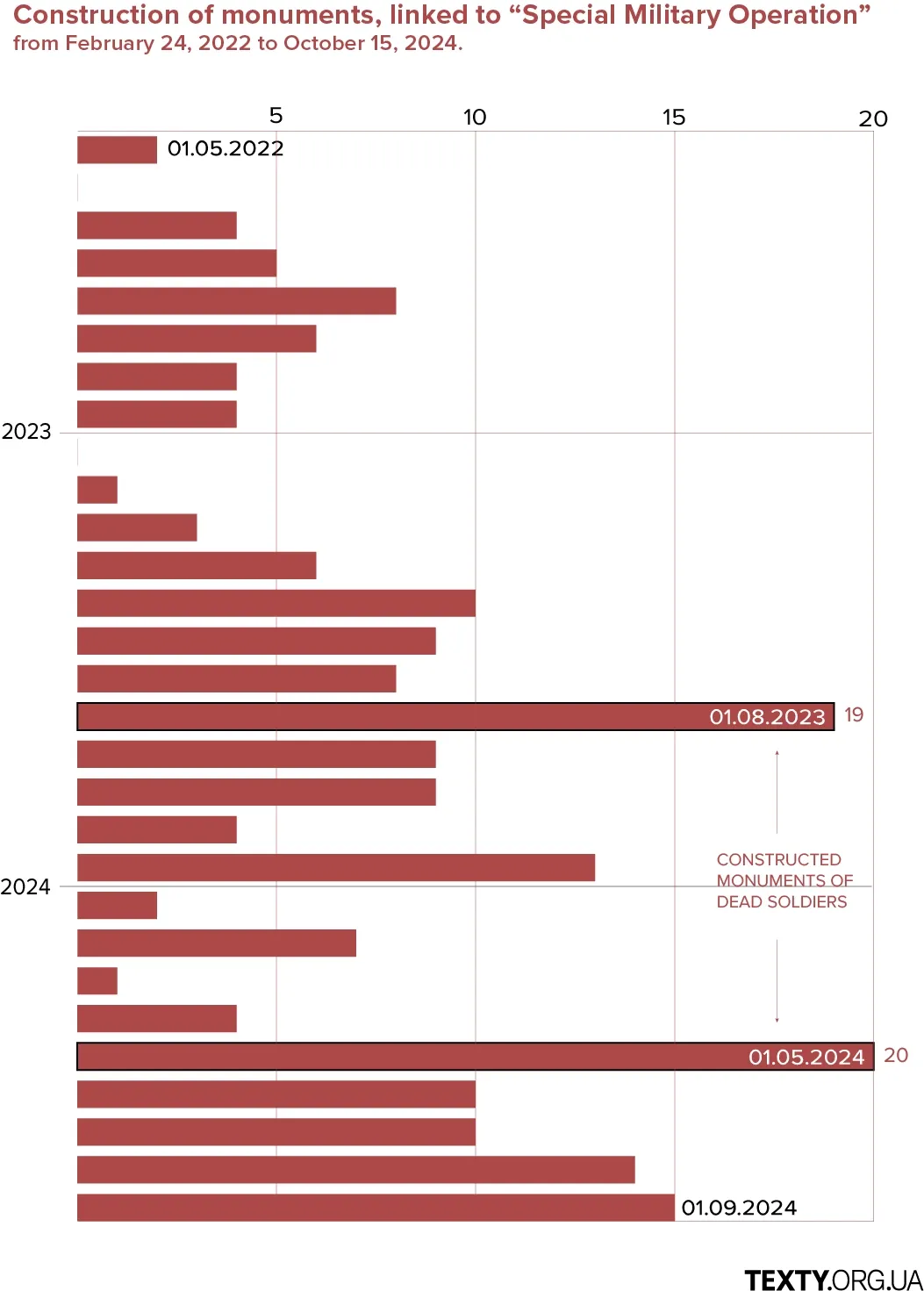

At the same time, a new cult of heroes is being formed — participants in the so-called "Special Military Operation" against Ukraine.

The killed occupiers are given the halo of new martyrs and heroes who fought for a "great aim."

Stories are spreading about how one soldier fought off the Ukrainian army or defended a trench by himself at the cost of his own life against the invasion of Western tanks. Here's a typical example of how "heroes" describe their deeds, and it's very similar to the descriptions of the "Great Patriotic War" heroes in Soviet textbooks: "Maksym Serafimov, as part of a reconnaissance unit, came under heavy fire from vastly superior enemy forces. He organized a defense and held the building with his men for more than ten hours, killing 30 enemies and an armored personnel carrier. When a grenade fell nearby, he covered it with himself, saving his comrades."

The death of soldiers becomes the main tool for the formation of a modern "cult of death," when Russian soldiers recruited for the war go on aggressive attacks for months, day after day, despite heavy losses.

Interestingly, the first monuments to the dead appeared three months after the outbreak of the war. The Kremlin's ideological apparatus, faced with heavy losses in the early days, probably did not know how to present them to its population at first.

"Investments" in plaster and bronze

Amidst the war and sanctions, Russia spends a lot of money on monuments.

It's about installing sculptures and accompanying PR campaigns: media coverage, outreach, and celebrations. This campaign begins with the announcement of plans to erect a monument. It continues until Russians are reminded of what this person is known for and why it's important to remember and perpetuate his memory. The public, sometimes even schoolchildren, participate in the ceremonies.

In this way, citizens are directly involved in shaping memory policy, unlike in Soviet times when Russians were only spectators.

Local authorities are responsible for erecting monuments to heroes of "Special Military Operation." They issue orders and regulate the algorithm for constructing such monuments.

Russian oligarchs finance more significant projects. Konstantin Malofeev, an "Orthodox oligarch" and owner of the Spas media resource, is building a monument to the Saints and Alexander Nevsky, Gazprom is donating a monument to Peter I, the 13th in the city, and plans to erect a "triumphal pillar in honor of Russia's victory in the Great Northern War."

The central government is responsible for the overall "historical line" of monument construction, i.e., it determines who it wants to see on the pedestal and who should be demolished and forgotten.

Directing history

The participation of the Russian dictator in various historical celebrations is not just a state ceremony but a demonstration of the ideological orientation of Russian memorial policy.

On September 8, 2022, Putin remotely opened the Savur-Mohyla memorial complex (Donetsk region)

The Savur-Mohyla in the occupied Donetsk region, once a symbol of the fight against Nazism in World War II, has now become a place where the "heroes of Novorossiya" — the soldiers of the Russian hybrid invasion army of 2014 — are also honored. According to the Russian authorities, this place now also symbolizes the latest struggle of Russia and the "people of Donbas" against "Nazi" Ukraine.

The memorial has become part of a broader Russian narrative that proposes to view the history of the Russian-occupied territories in eastern Ukraine as the "history of Novorossiya," a separate entity whose reunification with Russia was an act of historical justice.

November 22, 2022 Putin unveils a monument to Fidel Castro (Moscow)

Fidel Castro was a Cuban communist revolutionary and dictator. Under his rule, Cuba became a one-party state with communist rule. Castro allowed the USSR to deploy nuclear weapons in Cuba, triggering the Cuban Missile Crisis of 1962, one of the key incidents of the Cold War.

For Russia, Fidel Castro symbolizes the struggle against the United States, disobedience to the West, and support for anti-American sentiment.

Monuments to other foreigners unveiled in Russia have a similar significance.

Charles de Gaulle (bust in Volgograd). His decision to withdraw his country from NATO military structures in the 1960s challenged American hegemony in Europe. It resonates with Moscow's current rhetoric against US dominance on the continent and its attempts to split the allies and oppose the United States in Europe.

Nelson Mandela (monument in Moscow) symbolizes the fight against colonialism in Africa. By colonizing neighboring nations, Russia actively promotes itself in the world as a fighter against Western colonialism. This positioning helps to develop relations with the countries of the Global South, particularly in Africa. That is why monuments to Mandela are being unveiled.

Simon Bolivar (a monument in Moscow) symbolizes the fight against colonialism in Latin America. "Bolivaromania" is a popular cult in Venezuela, Russia's ally in the international arena.

Ho Chi Minh (monument in St. Petersburg) symbolizes victory over the United States. His struggle for Vietnamese independence from French colonialism and American influence reflects a long-standing propaganda line about Russia's alleged fight against colonialism and opposition to the West.

On January 27, 2024, Putin unveiled the "Memorial in memory of civilians who became victims of genocide during the Great Patriotic War" (Leningrad region)

Russia is trying to equate the Holocaust with the Nazi crimes against the Soviet population in the occupied territories of the USSR.

This equation is an attempt to use horrific historical events for modern political purposes, shifting the focus from the Holocaust as a systematic extermination of Jews to the suffering of the Soviet people as a whole.

Russia seeks to create a new narrative in which it appears not only as a victor over Nazism but also as a victim of genocide, which would allow it to claim a special status in international law. It reinforces the myth of the "great sacrifice" of the Russian people, which helps the authorities to legitimize their political ambitions on the world stage. However, this narrative ignores a simple fact: most of the "Soviet people" who suffered from the German occupation were not Russians but Ukrainians and Belarusians (read more about this in our project here). Moreover, it classifies these two people as Russians.

On July 28, 2024, Putin unveiled a monument to Admiral Fyodor Ushakov (St. Petersburg)

For Russia, Fyodor Ushakov is one of the creators of the Black Sea Fleet and the builders of Sevastopol. He never lost a single battle, never lost a single ship.

He is an ideological symbol of modern Russia. In 2001, the Russian Orthodox Church canonized Ushakov as a "saintly righteous warrior." His image fits into the concept of the "Russian world," an idea that combines military power with Russia's spiritual mission.

After Putin opened the monument, busts of Ushakov were simultaneously constructed in other cities. On August 5, the same day, they appeared in Azov, Petrozavodsk, Ryazan, Yeysk, and the occupied territories of Sevastopol, Donetsk, and Skadovsk.

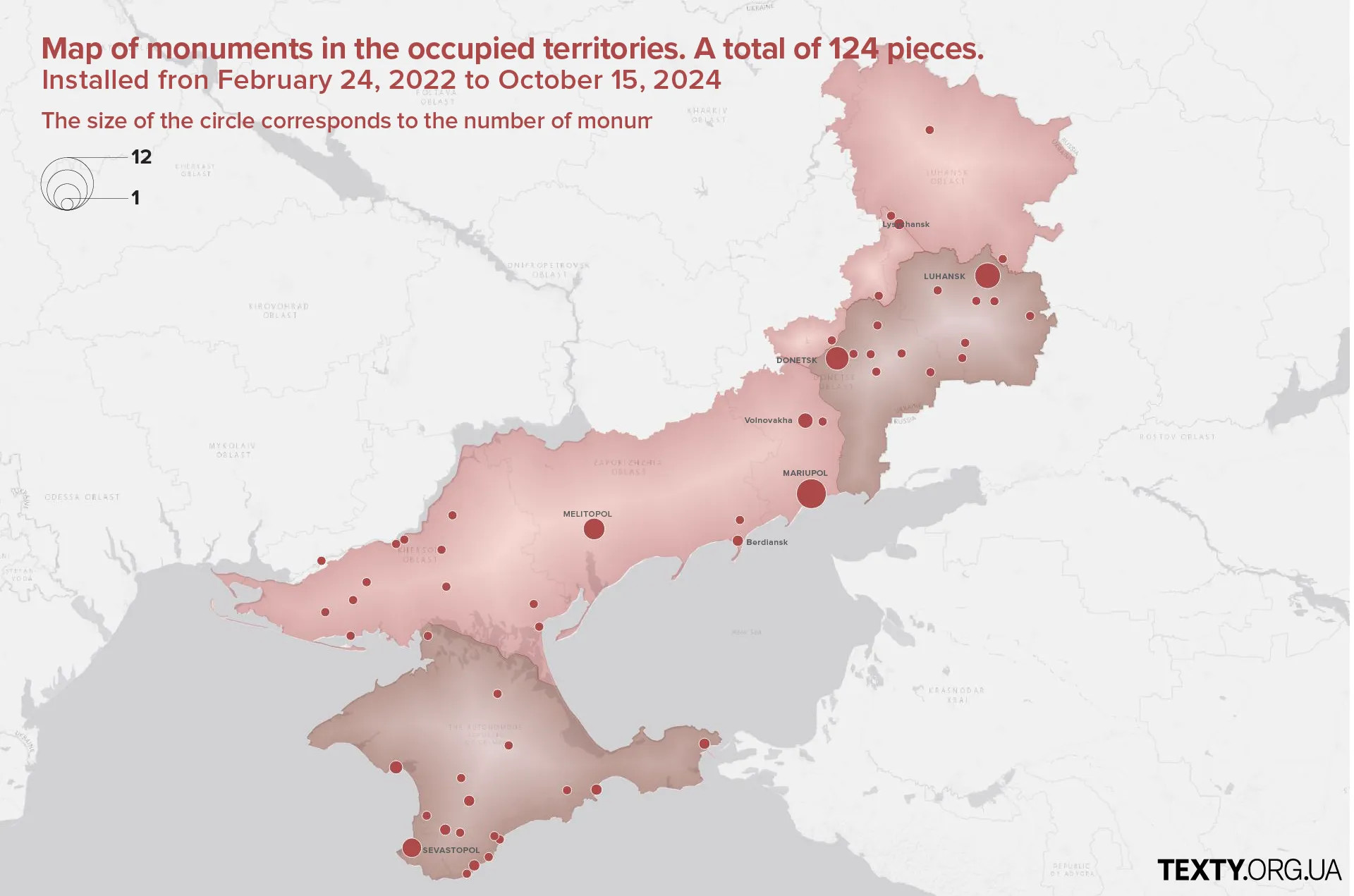

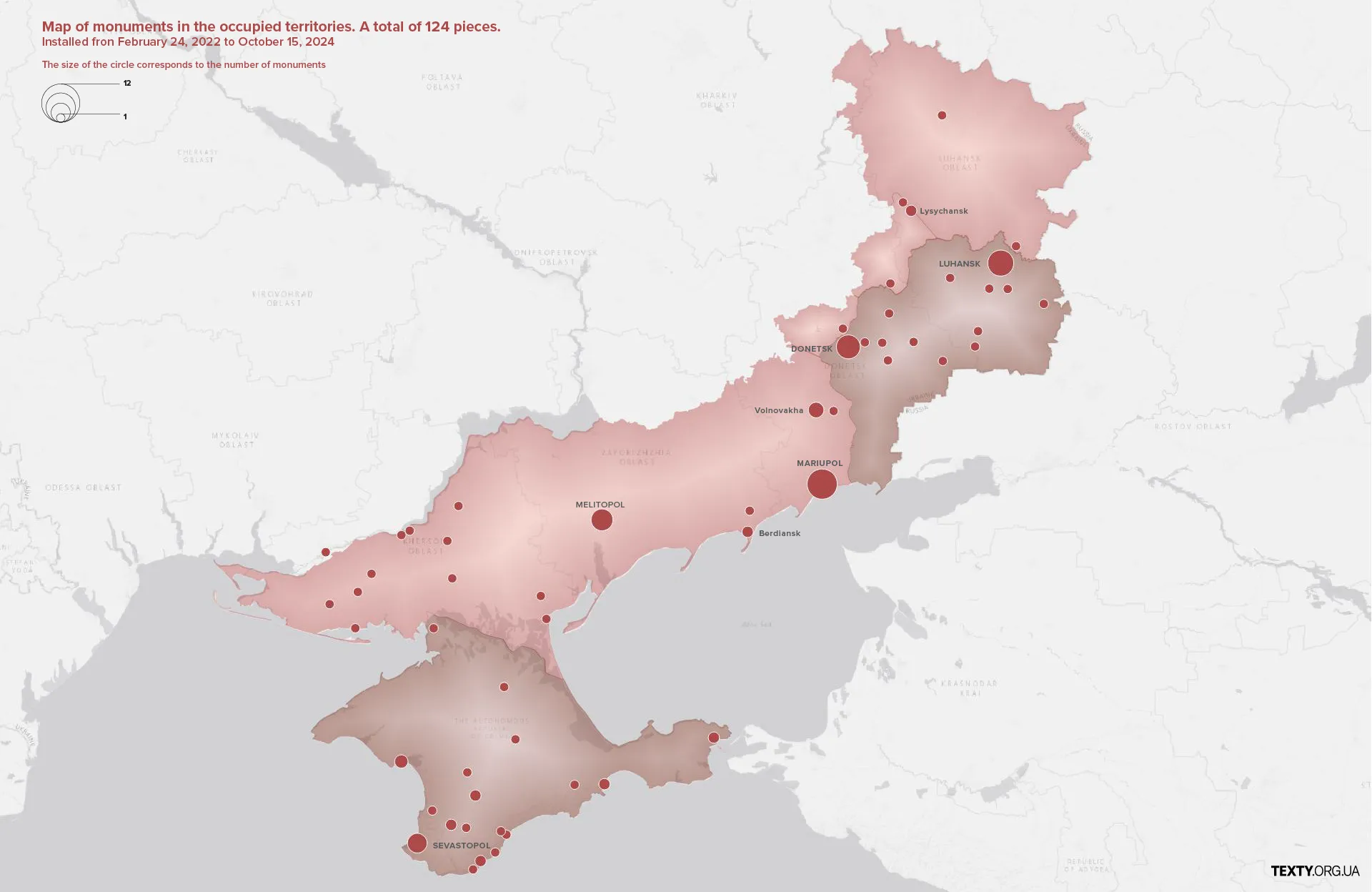

Strategy for the occupied territories

In the occupied territories of Ukraine, the first deputy head of the Russian Presidential Administration, Sergey Kiriyenko, is responsible for monumental propaganda. He checks the results of monument construction.

He was involved in opening three memorial complexes in the "DPR," two in the "LPR," and one in the occupied territories of the Zaporizhzhia region, as well as several monuments.

Kiriyenko also initiated unveiling a monument to the "grandmother with a red flag" in Mariupol. This is, in fact, the first monument not only in the occupied territories but also in Russia itself, directly related to the full-scale invasion.

In total, we identified 124 monuments erected in Ukraine's occupied territories during the Great War.

Russia's strategy in the occupied territories is to perpetuate the memory of the Great Patriotic War, to perpetuate the memory of new "heroes" — "defenders of Donbas" — and to try to establish their Russian historical narratives there.

That is why monuments to Alexander Nevsky are unveiled in Donetsk and Mariupol, and the cult of Fyodor Ushakov is being promoted in Donetsk, Mariupol, and Skadovsk. These people had nothing to do with these territories at all.

Monuments to Lenin are also being actively restored in the newly occupied territories. We found 13 of them. Russian propaganda has long argued that Kyiv's "Nazi essence" is due to the process of decommunization in the country. Therefore, the restoration of Lenin in the occupied territories serves as a symbol of the population's liberation from the "Kyiv regime."

Cultural cleansing

In the occupied territories, Ukrainian monuments are destroyed in the same way as any other manifestations of our identity. For example, monuments to the victims of the Holodomor famine are being dismantled, and the monument to Cossack hetman Petro Sahaidachny, who was even called the initiator of the genocide, is being demolished.

The occupiers are trying to erase everything that reminds us of Ukrainian culture, endangering historical monuments that testify to the struggle of the Ukrainian people for freedom and independence. By destroying these symbols, Russia is trying to destroy the very memory of the Ukrainian roots of these territories.

Methodology

We studied news about the unveiling of monuments on the websites of popular Russian media, on regional Russian telegram channels, and Telegram channels in the occupied territories of Ukraine. The list of media outlets and Telegram channels can be found here.

We collected all the publications posted on these resources between February 24, 2022, and October 15, 2024. We used Python programming language tools to identify news that contained words related to the subject of the study. In particular, these are the words "monument," "memorial," "bust" and their derivatives.

In the next stage, news that was not related to the topic of the study was eliminated: about the reconstruction of monuments or their damage, about monuments not related to Russia.

After forming a new sample, we manually checked each news item and extracted information about monuments (memorials, busts), to whom they were erected, date, and location.

Categorization and grouping were also done manually.

Attention: In our study, we could have missed a monument installation if the information about the event did not appear in the news feed on the monitored resources or if Python tools could not accurately extract the news according to our queries.