Hundreds of Steps. How many flights do residents of high-rise buildings have to climb each day when the power goes out?

"At least I'm getting some exercise again," I joke whenever someone asks, "How are you?" "I live on the 20th floor." "Oh, I sympathize," is the usual reply. Sometimes I hear, "I get it. I’m on the 22nd." In that moment, the social distance between us seems to shrink significantly.

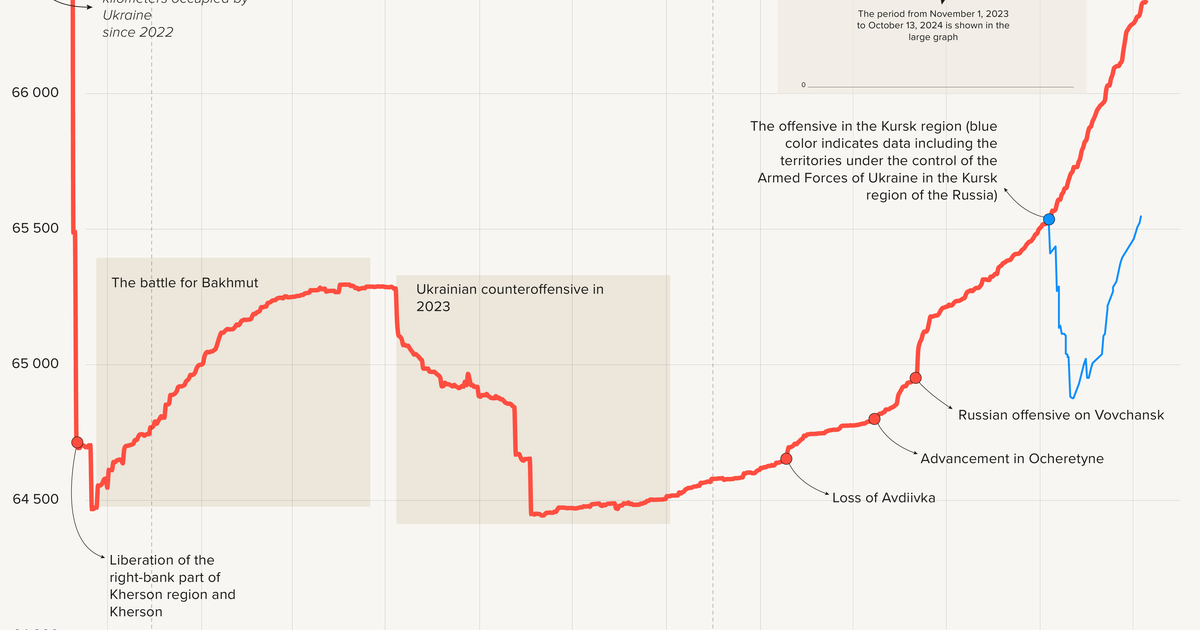

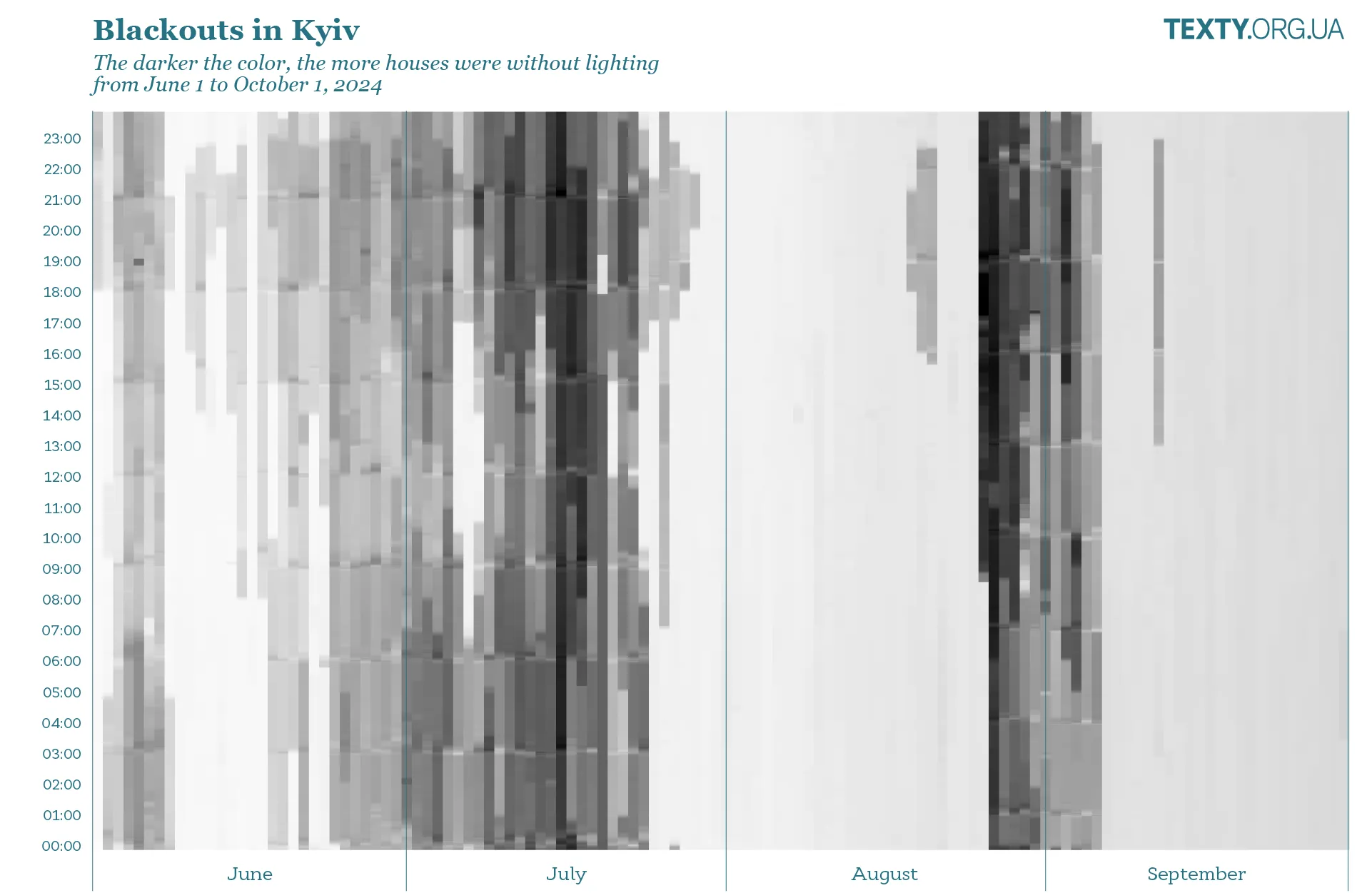

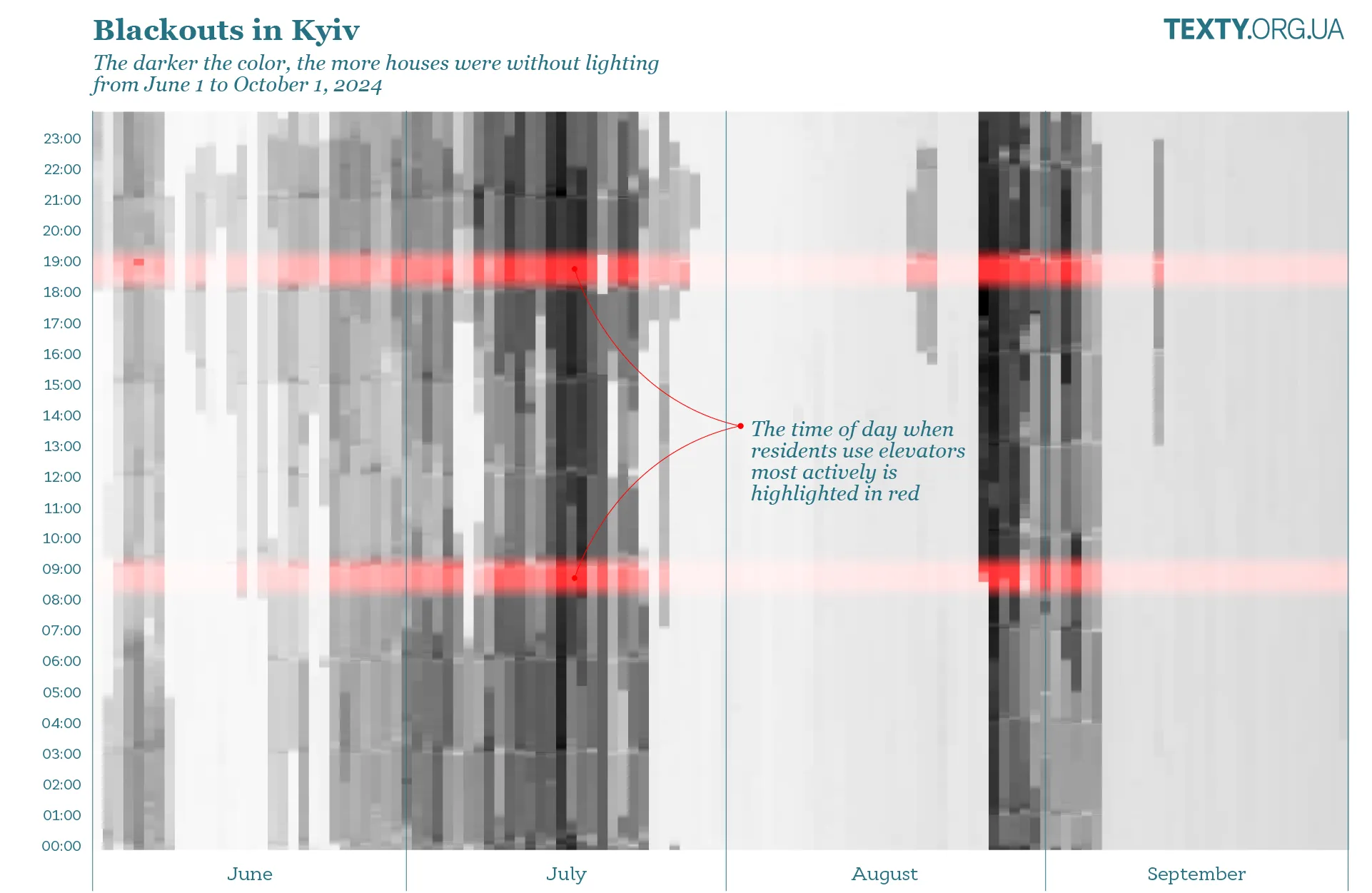

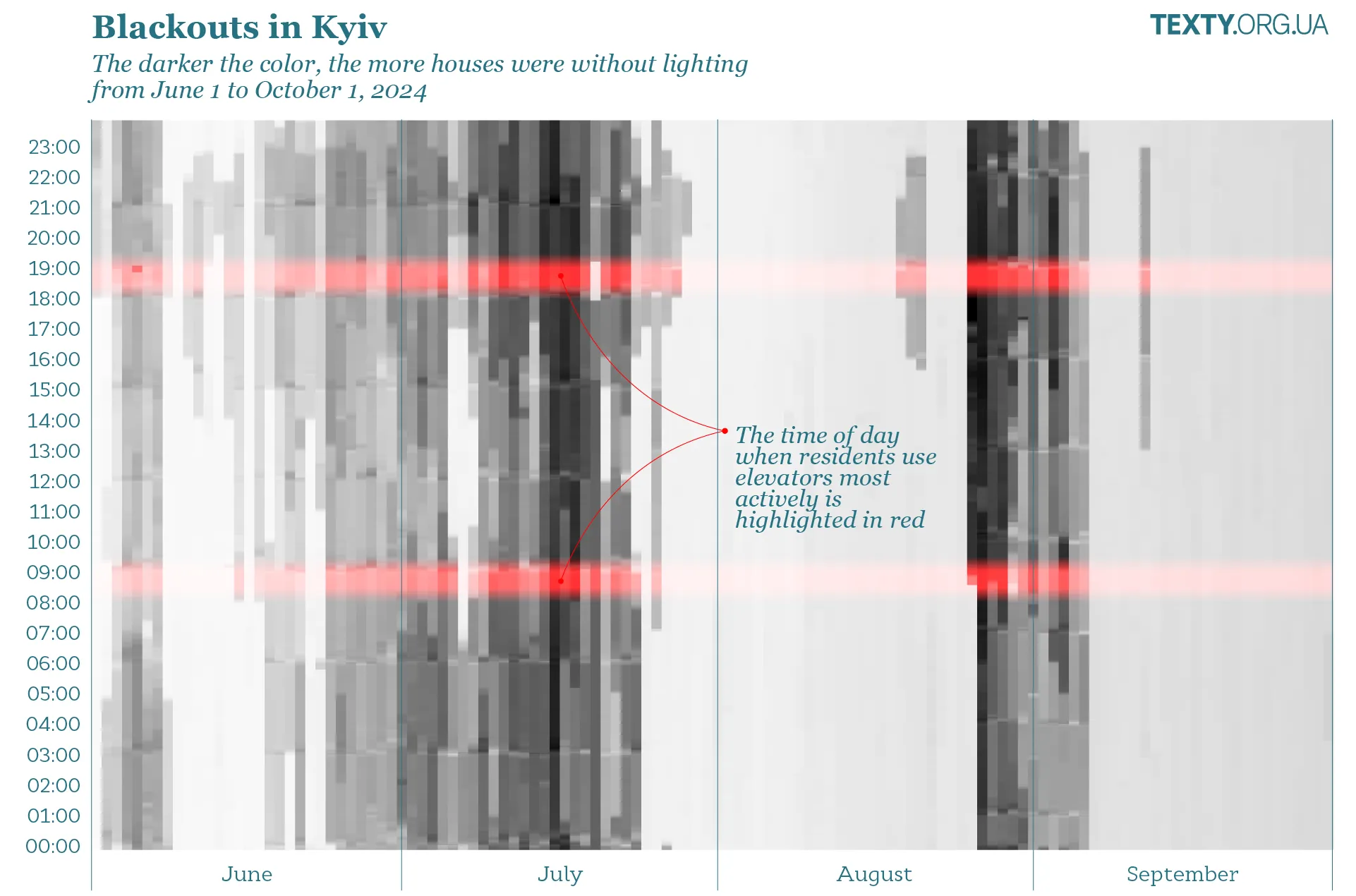

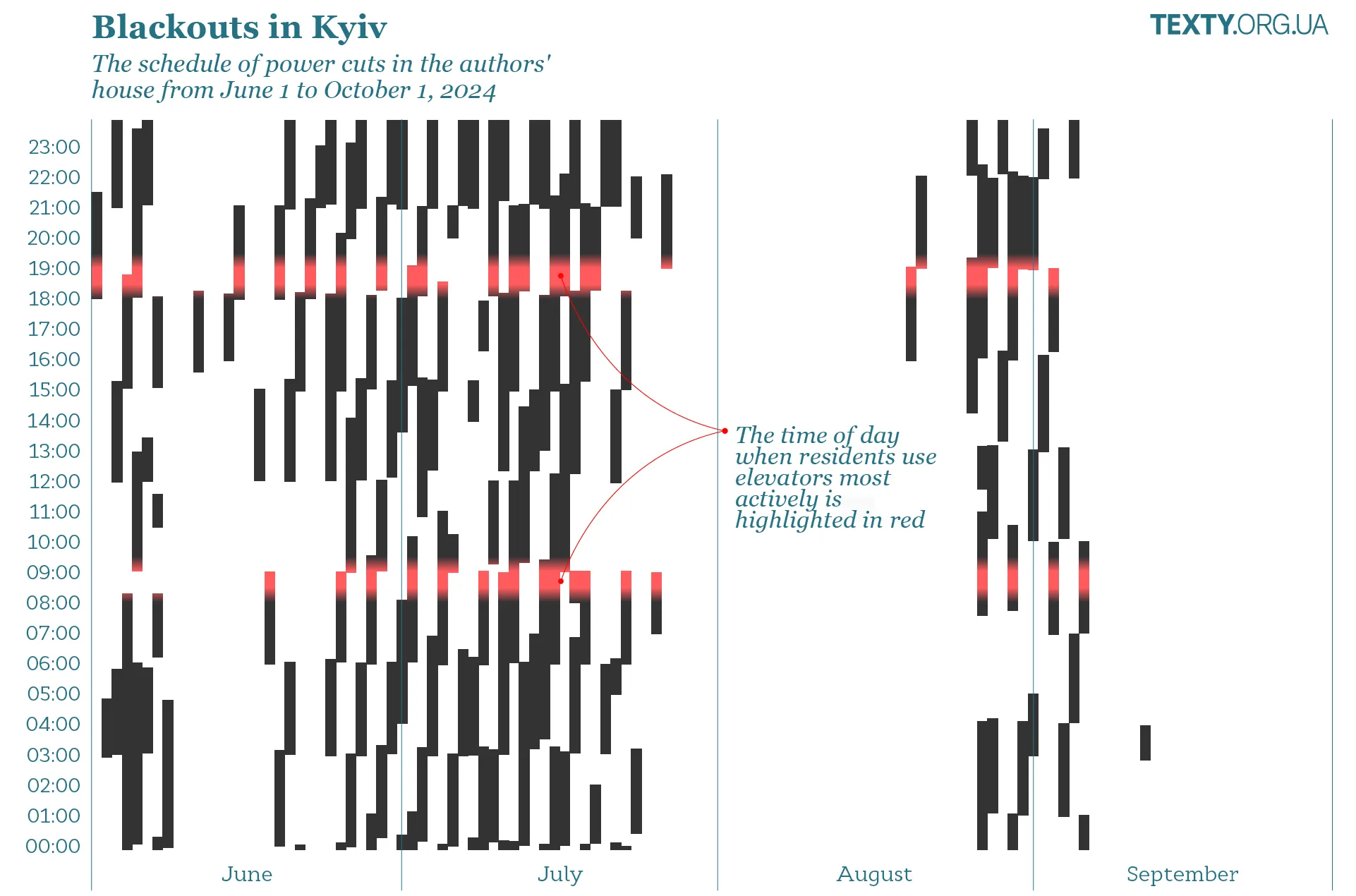

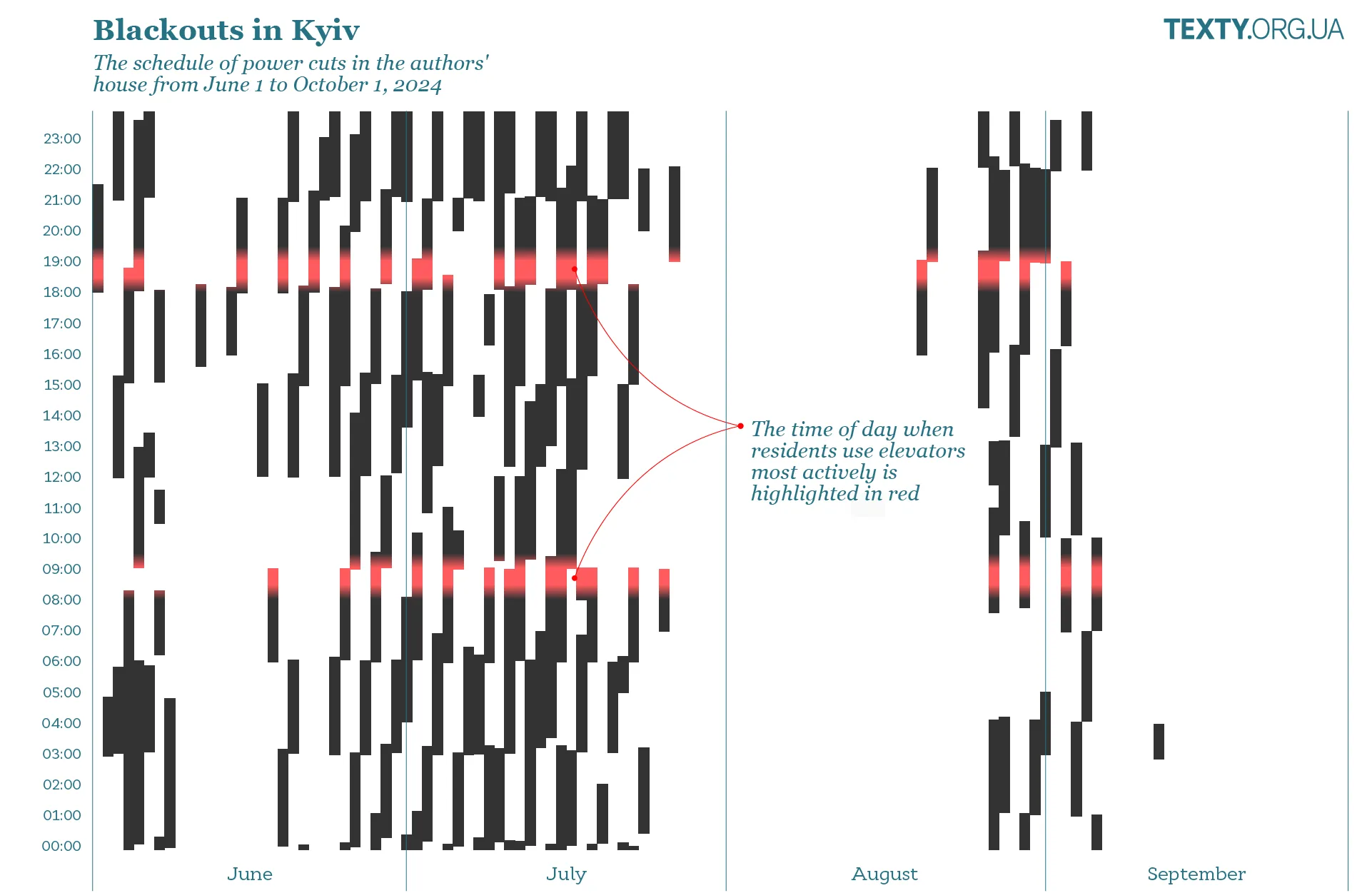

We analyzed data from the summer blackouts in Kyiv, and a similar situation may soon happen again.

Despite our tendency to cope with humor and memes, the reality is that Kyiv’s high-rise buildings—products of developers' profit motives and the city government’s inaction under various mayors—have made even the most basic amenities incredibly valuable for tens, if not hundreds, of thousands of people. With Russia’s ongoing attacks on Ukraine’s energy infrastructure, simple benefits like water, heat, the ability to cook, and taking the elevator have become luxuries. When the power goes out, all of this disappears in an instant.

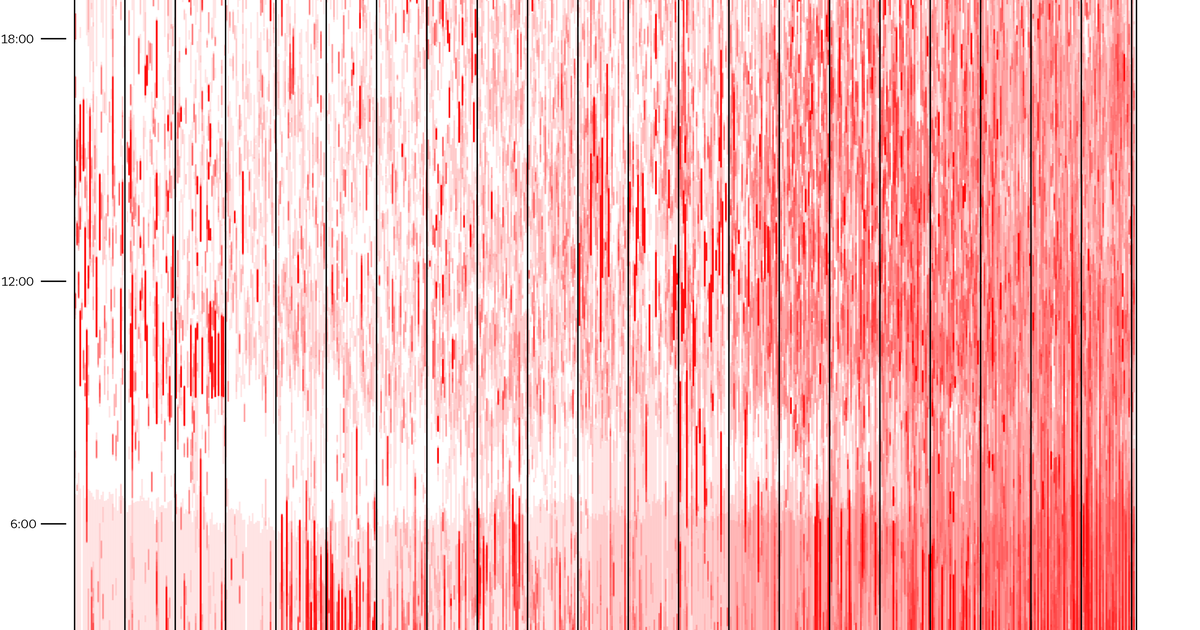

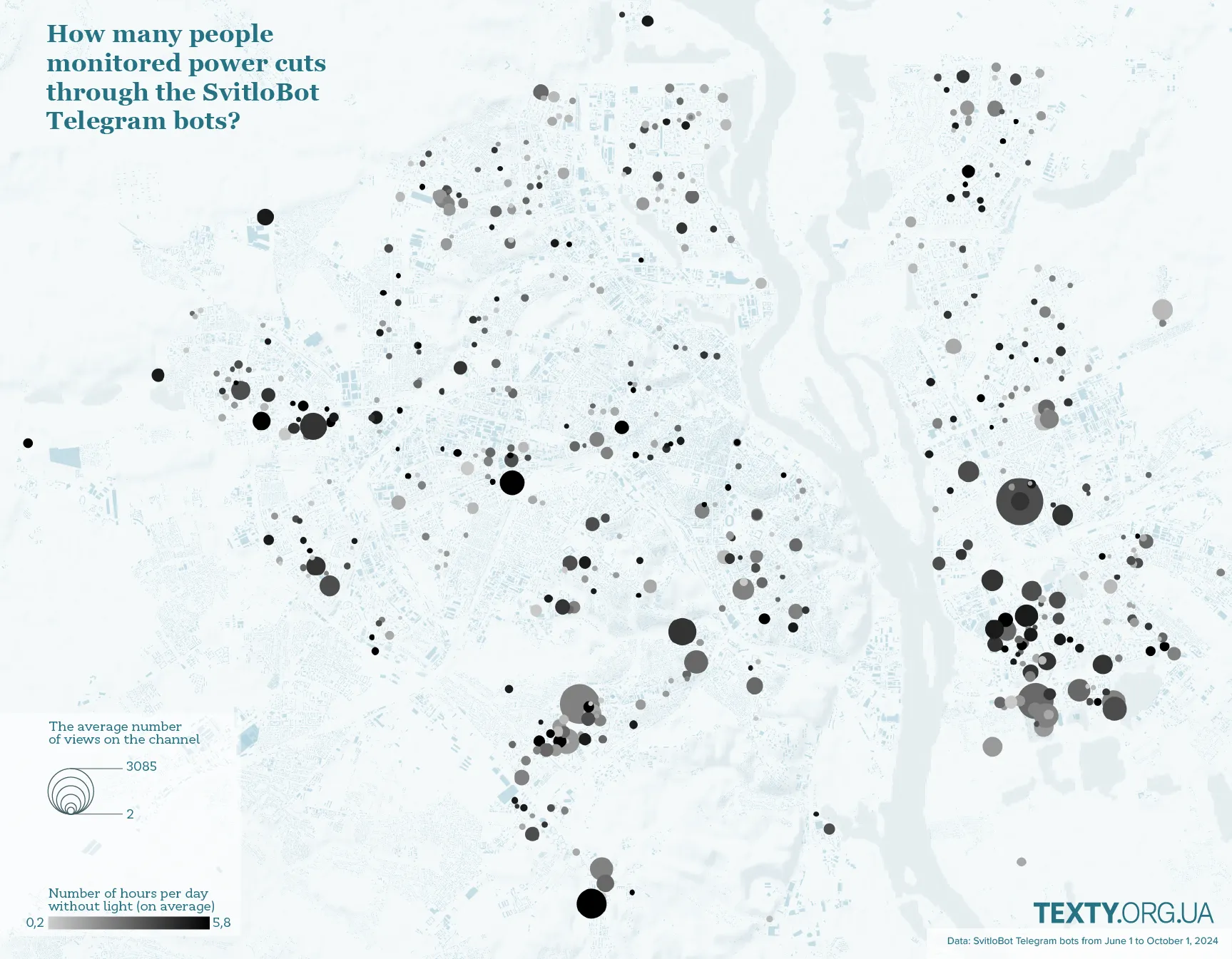

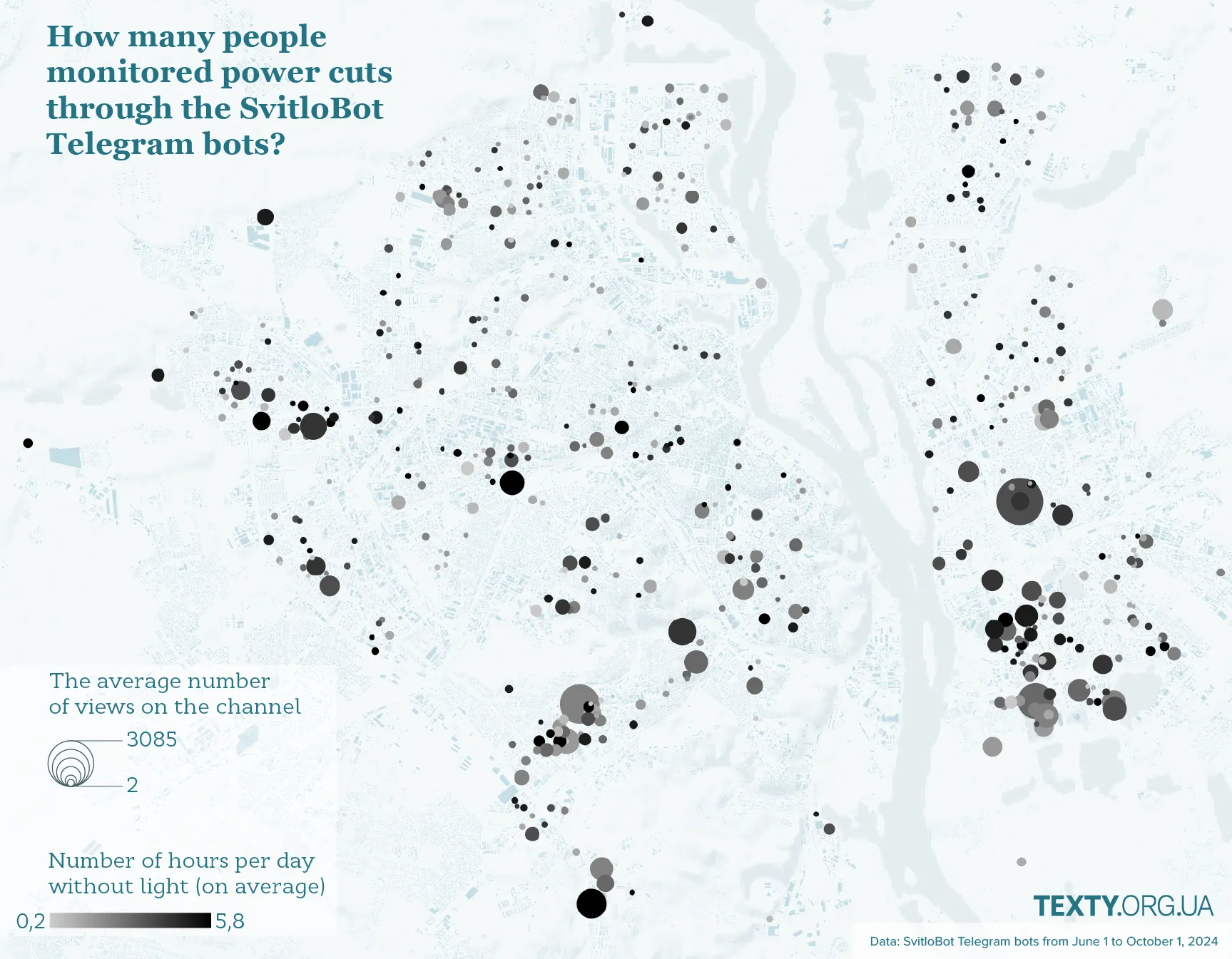

To understand the scale of Kyiv’s blackouts this summer—an unfortunate situation that may soon return—we analyzed data from hundreds of Telegram bots, where thousands of Kyiv residents tracked each power outage and restoration daily. These dedicated bot users are likely the residents who feel the absence of electricity most acutely.

Our analysis included 550 Kyiv-based Telegram channels linked to the SvitloBot project, a community initiative that lets residents turn their router or an old phone into a power-status monitor, reporting light availability directly to Telegram. Until late August, when the Kyiv Digital platform added blackout monitoring, these bots were among the most popular tools for knowing when it was safe to take the elevator up.

It stands to reason that those most affected by power outages are the most vigilant in tracking them. The larger the residential complex or building hosting a Telegram bot, the more subscribers and frequent readers it has. If we were to map these bots, we’d get a clear view of Kyiv’s densest and tallest districts.

Everything but the elevator

Two years have passed since the first major blackouts, giving us time to prepare for the worst in a city of one million with a robust air defense system. But not everything can be managed independently or at home. And for many Kyiv residents, the biggest challenge remains the elevator — a challenge only overcome by physical stamina. That is, if you’re healthy enough, or if you don’t have small children or elderly parents to care for. Otherwise, missing out on food delivery is minor compared to the difficulty of calling an ambulance or getting to a hospital quickly.

Some buildings and condominiums have organized independent power sources for water supply and elevators, but this costs hundreds of thousands of hryvnias, which the Kyiv City State Administration is ready to reimburse — but only after installation. So, initial funds are still needed, along with an active condominium board (ideally with members from the upper floors, to keep everyone motivated).

I watched as residents on the lower floors of a nearby building complained about the noise and smoke from a generator. For them, the generator is only a nuisance; it doesn’t power their apartments or allow them to run an air conditioner, and it prevents them from opening their windows. Meanwhile, it supplies water to the upper floors, where noise and smoke are less noticeable.

This situation challenges my belief in the simplicity of energy independence.

We’re not ssed to it — We’ve adapted

I’m not from Pozniaki, but I also live in a 25-story high-rise on the city’s left bank. That’s why, back in the winter of 2022, I wrote about our stone fortress on the 20th floor—without electricity, water, or heat. At that time, we mapped out the full picture of blackouts in Kyiv and Lviv, tracking the darkest days and the most “effective” shelling.

Since then, much has changed. The way blackouts are organized has improved (which we’ll see in the data), and, as we joke at home, we’re not used to it anymore—we’ve adapted.

Now there’s a 100-liter water barrel in the bathroom, a small camping stove in the kitchen, a stocked supply of drinking water, a large charging station for the refrigerator, and a smaller one for the router. Fiber optic internet lets us work. The main priority is to get our child to kindergarten, and that’s where the real challenge begins.

380 Steps

Every day at 8 a.m., I leave the house to take my child to kindergarten. Forty minutes later, I come back to start my workday remotely. Then, I make the trip again at 6 p.m. to pick him up. In the evening, I’d love to head straight home, but it depends on the elevator’s availability. As you might guess, it rarely works both times.

One summer evening around 9 p.m., I was sitting on a bench outside the stairwell and asked my son,

– "Are you hungry?"

– "Yeah," he replied.

– "Then let’s go to a coffee shop, and I’ll get you something sweet."

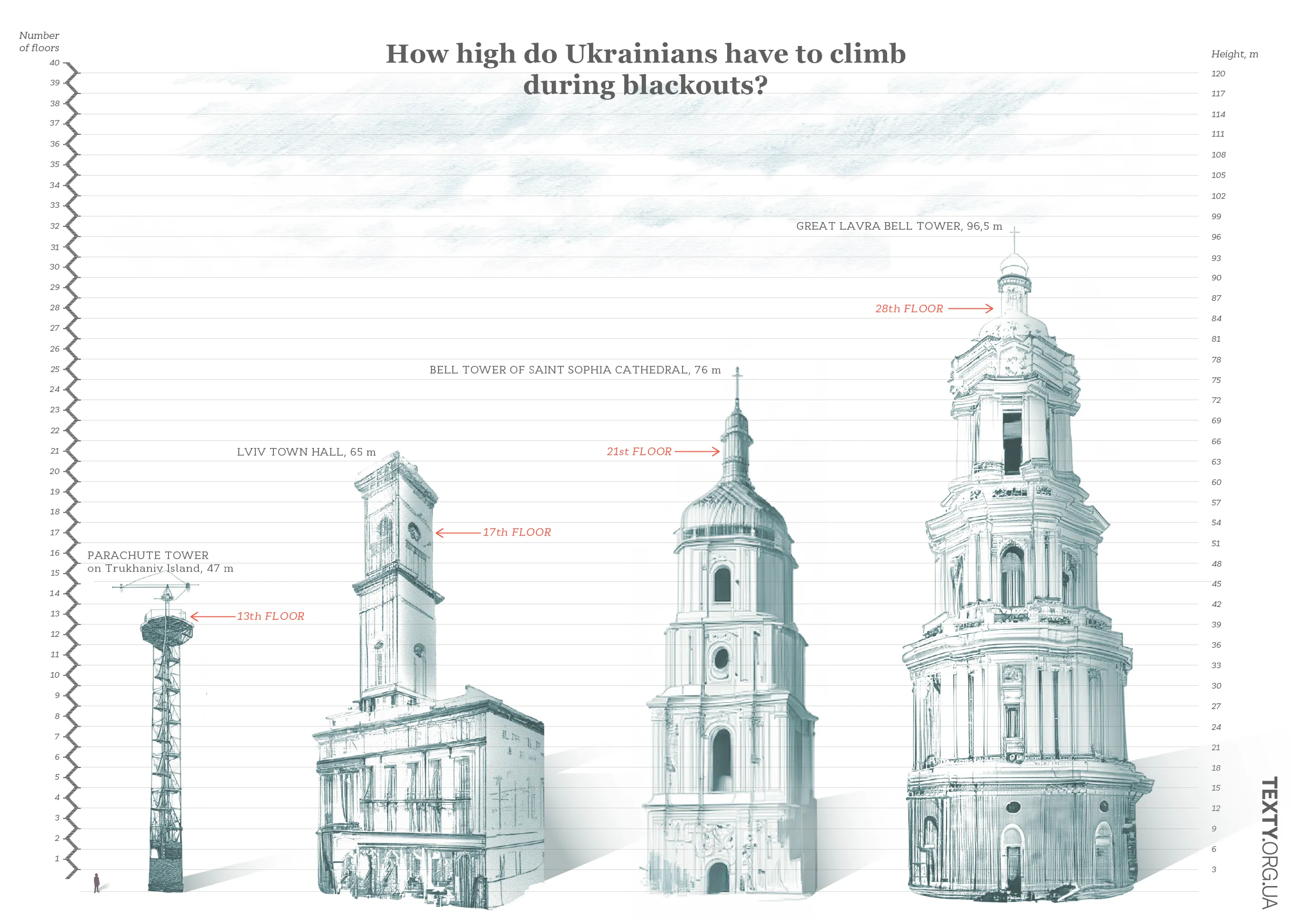

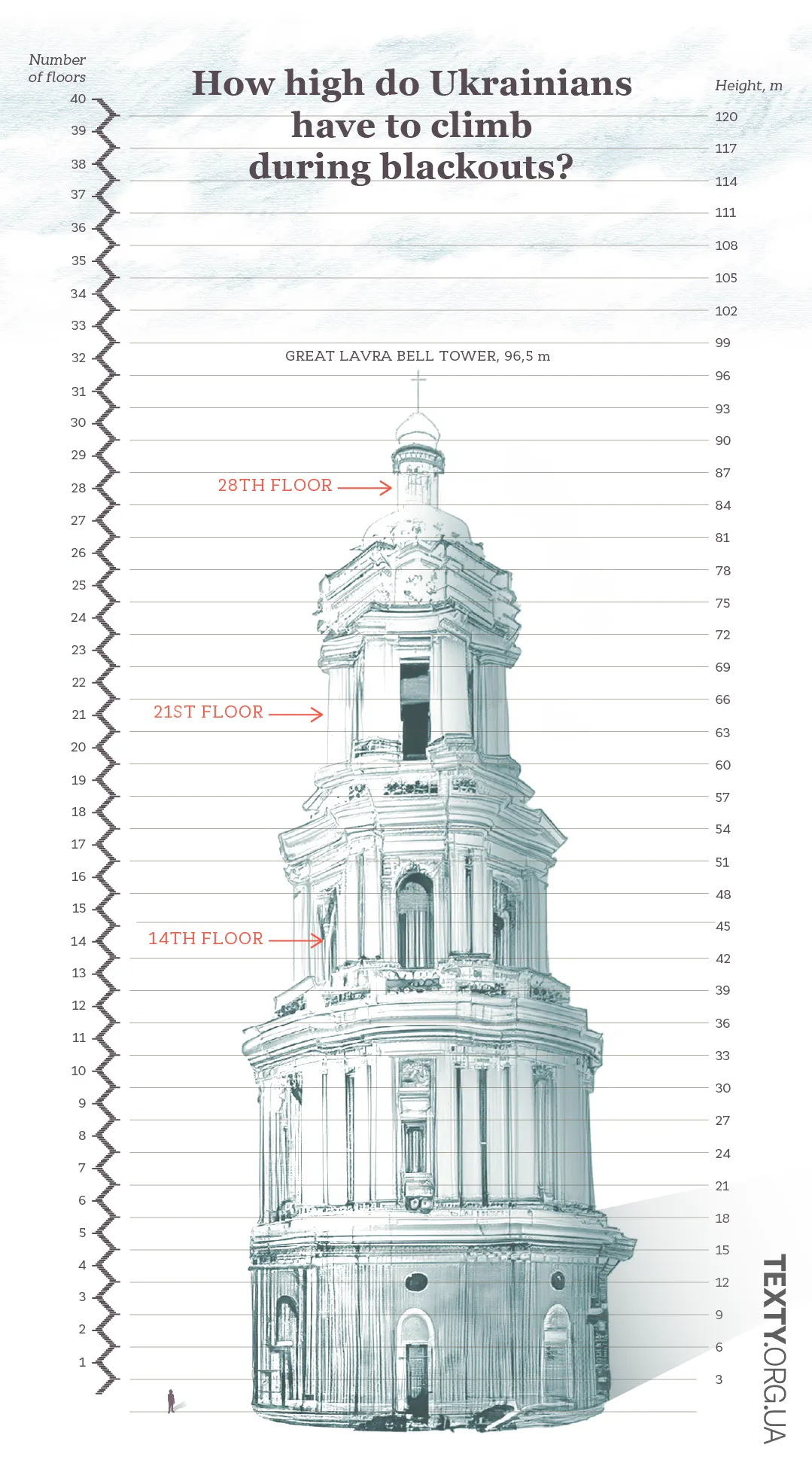

Feeding him sweets felt less daunting than climbing the 380 steps up to our not-so-beloved 20th floor.

Looking back at the blackouts of 2022, one thing stands out: they’ve become fairer, at least in my neighborhood. No longer do I look out from a dark window and see neighbors basking in light. Now, only 5–10 minutes separate the moment when power returns to each building in our complex.

In the darkness of the apartment, we can hear cheers and applause—louder than the hum of generators. It means power has returned to a nearby building, and soon, it will reach us too. And with it, a line of neighbors waiting for the elevator, who, like us, would rather extend their evening walks or support local coffee shops than face those stairs.

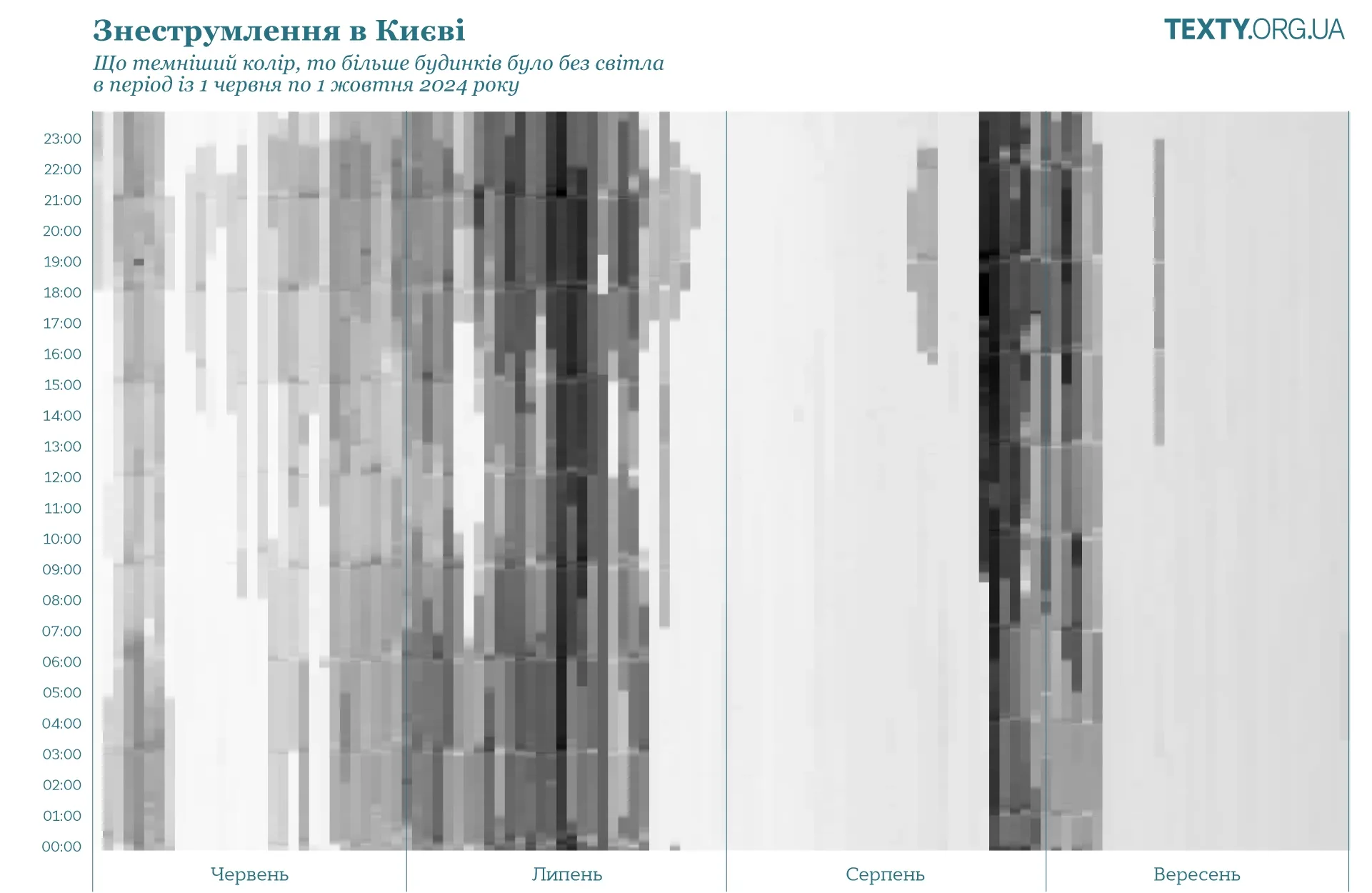

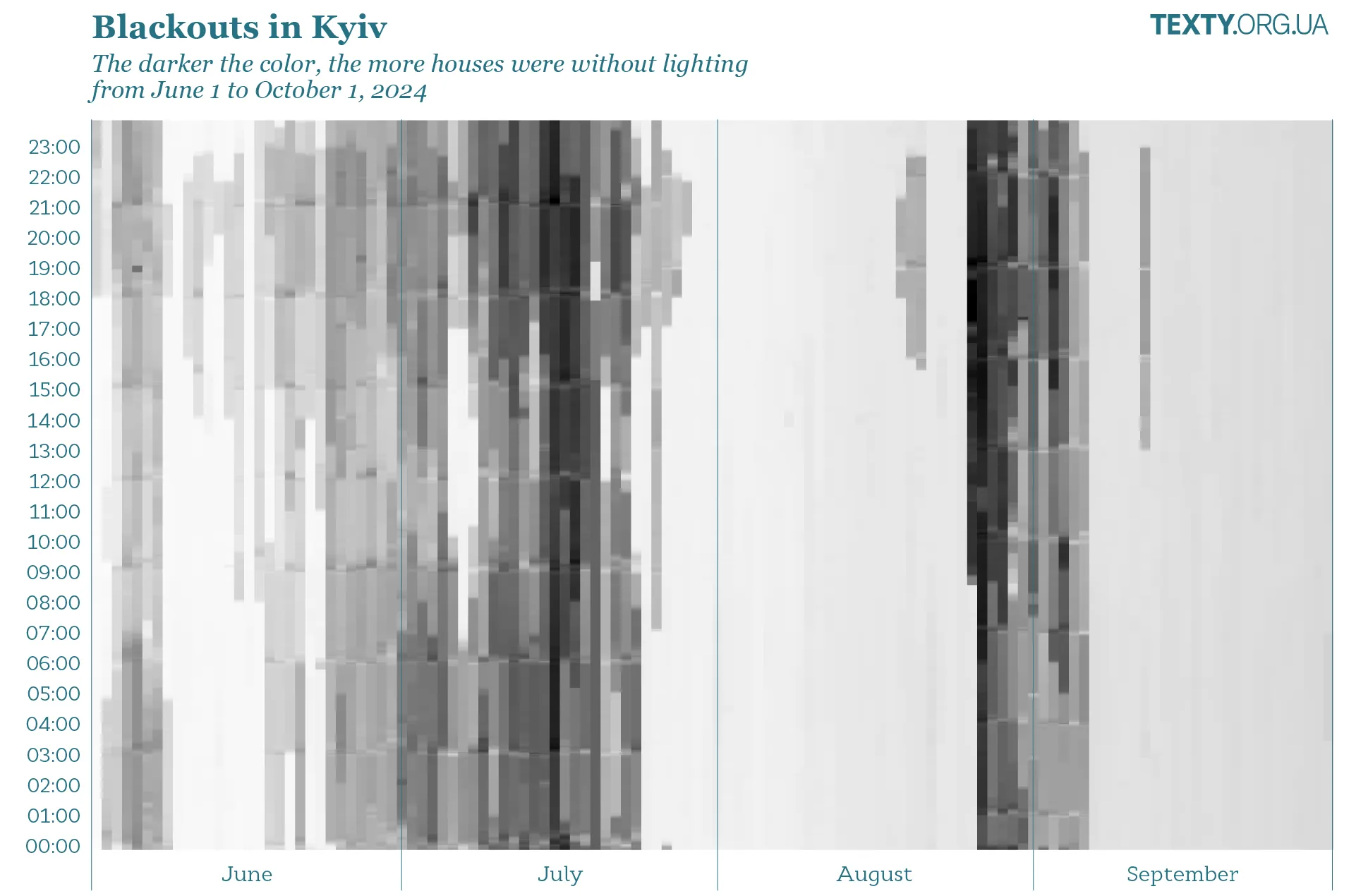

The blackout schedule also highlights the uniformity of intervals without power. Despite the unpredictability of shelling, electricity in Kyiv was frequently turned off according to a set schedule. Notably, the schedule was denser and darker around morning and evening rush hours.

* The darker colors toward the end of September reflect gaps in power restoration notifications from some bots, possibly because their owners turned them off.

This summer — and most likely this winter — Kyiv’s rush hour isn’t just about overcrowded public transportation and traffic jams. It also includes unusual activity on stairwells and a high demand for elevators and emergency services for those who didn’t make it out in time and got stuck.

We were fortunate never to get stuck. But like most Kyiv residents, we weren’t so lucky in other ways, spending 20 days without electricity this summer. There were 39 blackouts during "elevator rush hour." Of these, 18 occurred in the morning, when “just waiting it out” isn’t an option, and you’re forced to climb up with little chance for rest.

And now, with the lights staying on for nearly two months, I feel grateful every time I take the elevator.

Recently, I shared an elevator ride with a woman accompanied by two dogs and a restless three-year-old. Typically, in high-rise living, we’d nod hello at the entrance and barely recognize each other outside. But this time was different: she was heading to the 25th floor, and I wanted to remember her. Next time, I might remind myself that someone else has it tougher — and that I could offer empathy instead of complaint.

Small gestures, like staying positive, matter. That’s why my son and I still count each floor as we climb, often out loud. You’d be surprised how satisfying it is to meet a neighbor from the 8th or 10th floor and share a few words about the journey ahead. Even a small dose of sympathy from someone struggling with their own challenges — perhaps with illness or age — can make a difference.

Or, sometimes, we pause on a landing, catching our breath and tracking our progress better than by floor numbers. The cars look smaller, the playground shouts grow distant, and the outline of CHP 6 sharpens on the horizon.

This sense of appreciation once came only during sightseeing tours or city strolls. Now, every walk home feels like ascending the bell tower of St. Sophia in Kyiv. And visiting my mother’s place on the 16th floor? It’s almost like reaching the top of Lviv City Hall.

The most important thing is not to forget to admire the view — and to hope for good health for both my son and me, so that one day, if needed, doctors won’t have to make this climb "like a bell tower."