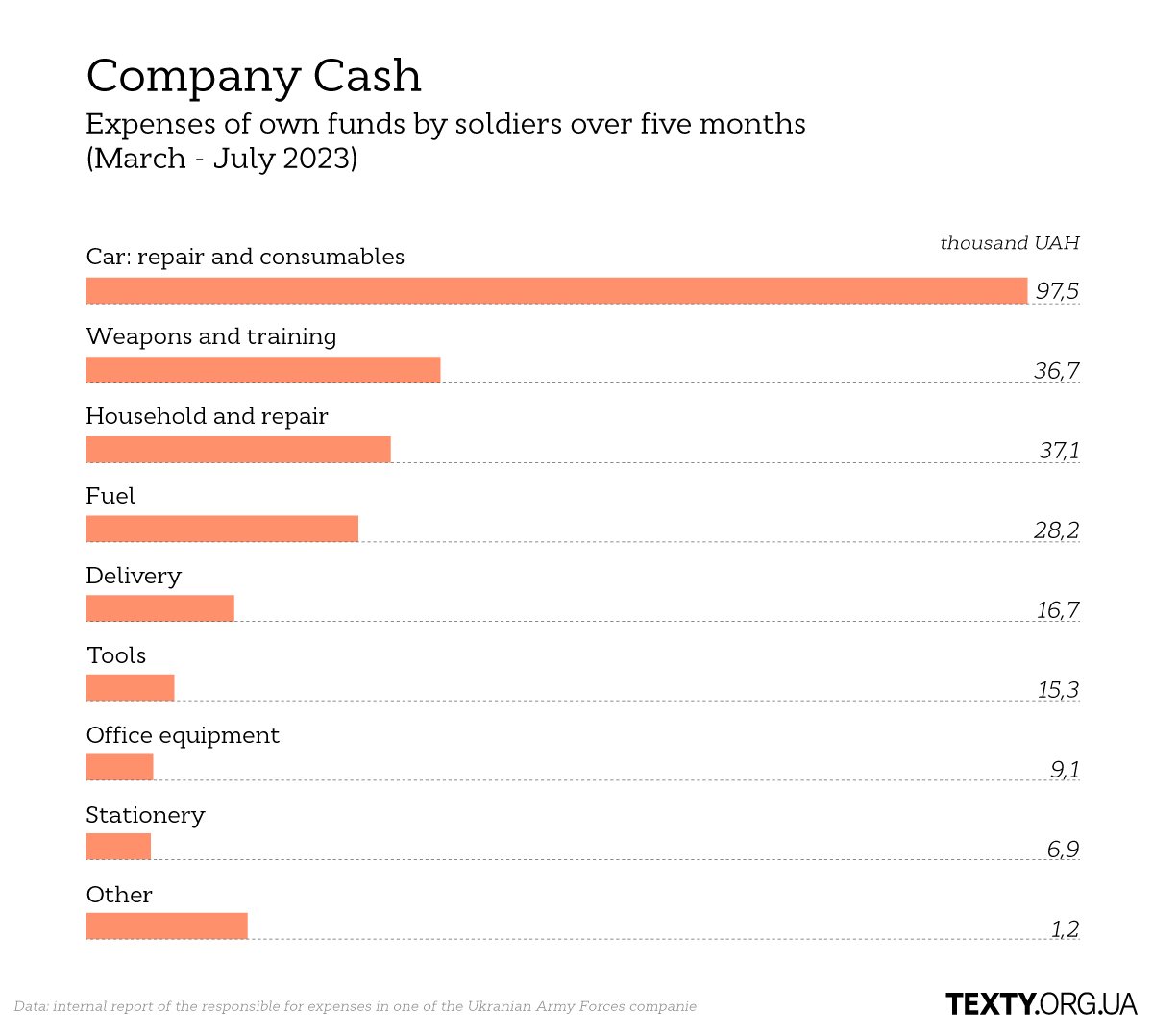

It's easier to buy with your own money. How company cash compensate for gaps in army logistics

Company cash is the money that soldiers donate from their monthly salaries for various everyday needs related to their service. This practice exists in almost all of the Ukrainian military units we spoke to.

This phenomenon is a vivid manifestation of the self-organization inherent in Ukrainians. Today, at the company level, the army actually has an informal system in place that helps units perform combat missions and maintain combat capability, compensating for the gaps in army logistics and the complexities of the outdated document management system.

Responsibility for spending joint funds is usually informally assigned to a trusted soldier. Most often, it is not the company commander (he has a lot of work to do) but a driver or car mechanic since the lion's share of funds, as we can see from the example of one of the units, is spent on maintaining vehicles in working order. Usually, a separate bank card is set up for these purposes.

A fighter who kept such records for several months in the company of one of the Ukrainian Armed Forces' combat brigades told us about how the money from such a fund is spent and why fighters started creating company cash desks. He also shared a few of last year's reports. We have systematized, anonymized, and visualized this data and asked for more details about the costs.

We are publishing an infographic and the soldier's story about what and why he has to buy at his own expense (here is his direct speech).

500 hryvnias from the salary

We usually give 500 hryvnias (approximately 12 US dollars - Ed.) every month. Some household items (nails, film, bags, disposable dishes) were bought without further discussion.

Large purchases had to be agreed upon in a meeting with the platoon leaders, who could accompany the squad leaders at their discretion.

Sometimes, they had to donate more money, for example, a thousand, especially when they received "combat" money (a reward for soldiers performing combat missions on the front lines - Ed.)

Fundraising is voluntary. Everyone was offered to donate, but some refused. No one was pushing them around.

Of course, there were conversations like, "You didn't give money for car repairs, so we won't take you to the post office next time," but in fact, nothing of the sort happened, at least in our country.

Cars: repairs and consumables

We had one pickup truck on our balance sheet and two unofficial vehicles, but we could not handle all the tasks with one car.

We need to transport people to the positions, to transport the sick and wounded (because medics often have broken down cars or no fuel), to go to the warehouse, to the post office, to solve various issues in the army services). Once, we took a soldier with an acute toothache to the dentist and another with an ulcer to the hospital.

All three vehicles were maintained largely at their own expense because it is unrealistic to get spare parts for pickup trucks brought from Europe —a t least, I have never managed to do so. They often break down and get damaged during operation in harsh conditions.

For example, a wheel damaged during a training exercise should be paid for by the person in charge. But this is unfair, so such expenses are covered by the company's cash.

We often bought paint and repainted the car when something was broken or damaged. We often broke car jacks made by Kozak, which are made in Ukraine, and it is easier to buy new ones than to explain why they broke and write them off.

It is theoretically possible to repair a vehicle on the balance sheet by a repair company or a technical support platoon, but it means paperwork and a queue for repairs that can drag on for months. However, I have heard of cases in other brigades where they had their trophy BMPs fixed in two or three weeks.

For example, during a counteroffensive in the Zaporizhzhia sector, a pickup truck fell into a ditch at night. The driver was trying to avoid the crater from the CAB, and an infantry fighting vehicle flew towards him. A door was bent, and something else was broken. Repairs were needed immediately because it was the only vehicle that could reach the zero positions on that broken road.

I bought the spare parts and went to the service station where we used to get repairs, but the mechanic was busy. I had to disassemble, align, and change something myself- my pre-war profession was related to metalworking.

In the end, I spent the whole day fiddling with it, and the car, though not perfectly, was driving. It is impossible to provide such a speed of repair “officially” in the army because you first need to draw up a technical condition report explaining why this condition has deteriorated, write a request for spare parts, and then bring all these documents to the relevant unit. When there is a free trawl, they will take it somewhere, put it in a queue for repair, and order spare parts.

We once handed over two Kozaks for repair in early February and received them in September or October. They were repaired very well, but it took so long! That's why armored vehicles were sent for repairs only as a last resort when they could no longer be used or repaired on their own.

Consumables often have to be purchased from the joint fund: glass cleaner, oils, antifreeze. Sometimes they are available in the warehouse, and sometimes they say they are not and you have to wait.

Frequent trips to Nova Post and delivery costs are also mostly related to car maintenance.

Fuel

The story with fuel is as follows: it is issued in the warehouse according to applications and reports, but for various reasons, there is always a shortage (it happened that there was no fuel at all for two weeks).

But the shortage is not because we are traveling on some personal business or selling it on the side. At least in our unit, this was not the case.

We used the money we raised to buy gasoline for the generator. Because the generator was issued to us, it was on the balance sheet as company property but not as a "consumer" of fuel and lubricants with a separate statement of expenses. So again, it was easier to buy it with our own money.

If a company has gasoline cars on its balance sheet, they sometimes take fuel from the "car" fuel account, and then slightly twist the speedometers to adjust the figures to fit the reports. But we had only diesel cars.

By the way, the speedometers have to be adjusted because the actual fuel consumption does not always correspond to the documentation. According to the documentation, the Kozak armored car consumes about 26 liters of fuel per 100 kilometers on the highway and 33 liters on a dirt road, while the standards are up to 28 liters.

But we hardly ever drive it on the highway. Instead, we drive through the sands and swamps with ten people on board (instead of the eight provided for) and a bunch of weapons. At one point, I even saw 56 liters per 100 kilometers on the dashboard. It's impossible to justify fuel consumption according to all the rules, and the difference can be significant. So, I had to adjust the mileage in the reports and on the speedometers to the actual fuel consumption.

Weapons and training

We used our money to cover the subscription fee for the starters and to buy various items that were difficult or impossible to obtain from the warehouse. For example, magazines for small arms to replace the lost ones so as not to bother with writing them off.

The worst thing is when magazines that came with the weapon are lost (and this happens often in combat). Then, you have to arrange for the dismantling of the weapon and fill out a lot of paperwork to write them off. Writing off lost weapons is a separate story outside the company's funds.

For some reason, our system believes that a person cannot lose a magazine or, God forbid, a whole assault rifle in battle, even if he is wounded. The cost of a magazine usually starts at 350 hryvnias, while good ones cost 800-900.

For example, a squad or platoon commander came and said: we don't have enough magazines; maybe someone else needs one. The others agreed that it would not hurt, wrote down how much they needed, and we bought them. We had democracy in this regard.

Another time, we bought several dozen training grenades to train newcomers. It was our initiative. We were not given them, nor were we given blank ammunition, by the way. And newcomers need to train on something.

In April, when we were in the Dnipro region preparing for the counteroffensive promised by the command, we bought two inflatable boats. The order to organize training to overcome water obstacles had been issued, but the boats had not.

We could not afford some expensive things like night vision devices from this cash register — we got some stuff from the warehouse, and volunteers helped us with some.

Household items, office equipment, etc

From household goods, we constantly bought various small items to equip dugouts and trenches (nails, fasteners, tools, etc.), raincoats, and a lot of packing and protective film, which is always needed to protect dugouts, trenches, and sleeping places from moisture, but for some reason is not supplied centrally. As well as colored tape on headbands to identify your own.

We even made tents for the trucks to keep the ammunition from getting wet; we bought the materials and tools for this.

Expenses in the “office equipment” section include the “king of reporting” printer, which is a must-have in every company for printing numerous reports, acts, and statements. It is also unavailable in the warehouse, so you have to chip in, along with paper and pens.

The funniest thing is that the soldiers even had to buy a book of army property records (namely, Appendix 13) at their own expense — it was not in stock at the right time. But this is not a reason to be late with reports because reporting in the army, as well as the fulfillment of combat missions is above all.