Wrong turn. Why in the first days of the war, a lot of residents of the northern Kyiv region did not even think to evacuate

President Zelensky did not believe a full-scale invasion would happen and talked about barbecues in the spring – and the civilian authorities weren’t prepared for such a turn of events either. When Russia invaded, the government repeated optimistic reports that Ukrainian forces were successfully repelling the attacks. It cost the lives of those who took that message at face value and did not leave the soon-to-be-occupied territories in time. Others even moved to the occupied territories in a naïve hope to sit out the period of hostilities in a quiet area away from Kyiv.

Читати українською

Translated by Dmitry Lytov & Mike Lytov

"Don't panic"

In the first days of the war, one could easily fall into the hands of the occupiers or say goodbye to their life by simply taking a turn to a "wrong" street when leaving their hometown or village. Such incidents happened mainly due to the lack of honest reports from the authorities. We know of a case when a family managed to avoid the occupation after reading a post by amateur analyst Tom Cooper. He tracked the movement of troops from open sources and posted his own analysis of the war events; people read his reports, found out what was still under Ukrainian control and where the Russian occupiers were, which roads were (still) free - and that's how they were saved.

Such reports should have been provided by the authorities, but they failed to provide them under the pretext of maintaining secrecy. But was it actually a fear of speaking frankly: how could they admit that the enemy took towns far away from the frontline while the possibility of an invasion had been rejected for months?

Another problem was their inability to come up with a plan for the worst-case scenario and follow it.

We do not claim that they should have considered and organized evacuation. But simply collecting and publishing true information about the advance of the occupiers could have saved many lives.

After the debates about the military readiness of the country at the beginning of the war, we forgot about another aspect of the conflict: namely, to what extent the Ukrainian authorities were ready to minimize the dangers for the civilian population.

The first rockets fell on Kyiv at 4:35 am — and no sirens warned about them then.

Simultaneously with the landing of the airborne troops near Hostomel Airport, the Russian troops began their march to Kyiv. To make matters worse, they were moving from the direction(s) where the Ukrainian authorities expected them the least (Translator’s note: they passed through the Chernobyl exclusion zone). The populations of all the satellite towns of Kyiv in the north gradually came under attack: Borodianka, Vorzel, Bucha, Irpin... Their population, of course, was not properly informed about how to behave in the conditions when the occupying forces were advancing on them.

"On the morning of February 24, we were driving through Irpin and Bucha," says Oksana, a resident of Kyiv. “The streets were full of people, some were standing in line at ATMs, some were shopping for groceries, many people were just standing in separate groups and discussing what to do next. The parking lots were full of cars — it seemed that the panic there was much less than in Kyiv. I understand that the majority did not have any clear plan of what to do next."

Residents of Kyiv, preparing for the offensive, read articles about the war, which were based on the experience of Donbas in 2014. Both these publications and their numerous trainings taught them that it would be worth leaving the big city during hostilities. This is exactly what the Kyivans did. On the other hand, residents of nearby towns believed that they were relatively safe, because they did not think that they would come under rocket fire and that the enemy would enter their towns. And they also believed that they would have access to food and water in case of any development of events.

Residents were leaving Kyiv in droves, with traffic jams on the roads, while the authorities continued to stick to the policy of “not spreading panic." In his evening speech on February 24, Volodymyr Zelensky said: "In the north of the country, the enemy is slowly advancing in the Chernihiv region, but there are forces to hold them there. (In fact, as we showed in the article about the defense of Chernihiv, at 2:00 p.m. Russian troops were already only several kilometers away from the city — TEXTY) A reliable defense was built in the Zhytomyr region (There is recorded evidence that the Russians entered the Zhytomyr highway, on which the people of Kyiv were evacuating to the west, on February 28, but people did not even know about it and kept driving on it to their imminent death — TEXTY) The enemy paratroopers in Hostomel are being blocked, the troops have been ordered to destroy them."

Information trap

However, as a result of all the efforts of the authorities, the inhabitants of the settlements that the Russians soon occupied fell into a kind of information trap. On the one hand, they were told about the need to provide information in doses so as not to inform the enemy of something important, and on the other - that the enemy was already fleeing, that it would only take "two or three weeks" before the enemy would start to break down.

Thus, the NSDC (National Security and Defence Council of Ukraine) stated that "forums and groups in the WhatsApp, Viber, Telegram, Facebook messengers of the Kyiv region were massively flooded with the same messages. The authors of the posts actively ask in different variations how to get to Kyiv, who can bring a small child to Kyiv, how to get from Brovary to Boryspil. All these posters had the same characteristics: they were new members of groups from the Kyiv region, they joined the groups only after February 25, and they mostly wrote in Russian." There were indeed certain grounds for such fears. Russian spies and saboteurs were caught here and there. But it must be understood that at the same time many ordinary Ukrainians were also trying to find out where to go and where it would be safe.

At the same time, already on March 2, the adviser to the head of the President's Office, Oleksiy Arestovych, said that "a psychological breakdown has occurred on the battlefield. That is, everyone knows that the enemy is mass-abandoning their weapons and equipment, surrendering or moving towards the Belarusian or Russian border." Meanwhile, the Russians controlled the Zhytomyr highway and shot civilian cars trying to drive through it.

People got a wrong and dangerous feeling that it would all be over soon, they just had to wait a few days.

"In the first days, it was psychologically very difficult to leave. I had a feeling that it would only take maybe two or three more days until everything would somehow clear up. On February 28, I consulted with the head of the housing cooperative and my neighbors about leaving, and everyone persuaded me not to leave the home, they said that enemy sabotage groups were roaming in the forest, so it was safer to stay here," says Inna, a resident of Irpin. "Consequently, everyone had to leave in March, but most of the neighbors left the city already when the fighting was going on."

Unfortunately, the situation did not change. It was quite the contrary: fears arose in Kyiv that the residents of the occupied satellite towns could be used by the Russian occupiers for their own purposes. It is not known where these rumors began to circulate, but rumors spread both in recently occupied cities and in Kyiv that the Russians would attempt to get into Kyiv under the guise of evacuating local residents.

This is what UP (Ukrainian Pravda online media) wrote about it, referring to Danilov, the secretary of the NSDC, and his own information from Bucha:

"The Ukrainian authorities are not evacuating residents from Bucha, which is near Kyiv, the Russians want to enter the capital of Ukraine under the cover of buses with civilians. Danylov (the head of the National Defence council) is quoted to say: "The Russians are gathering all of this to let these buses pass in front of them so that they can go to Kyiv." Residents of Bucha confirmed the information about the buses to the Ukrainian Pravda newspaper.”

However, TEXTY did not manage to find any confirmation that the occupiers were indeed attempting a masked invasion of Kyiv through an allegedly organized "evacuation" during those days. Although, of course, it is impossible to completely deny such a possibility. The Russians have repeatedly demonstrated their intention to cover themselves from fire by using the civilian population.

In conditions where it was quite difficult to get objective official information in real time, Telegram channels and other social networks became one of the main sources of information. It was on them where people could obtain the most updated information, including that about the movements of the occupiers. By the way, some state organs, in particular the State Emergency Service, have switched to social networks, notably Telegram channels, while their own official websites were disabled due to the threat of hacker attacks.

The only problem was that in the first days and weeks the information was quite fragmentary even on those online forms of media. Sometimes it was quite difficult to understand what was actually happening in the videos uploaded by local residents. To top it off, problems with the Internet began.

The only ones who gave a complete picture of the course of the enemy's offensive were the General Staff of the Armed Forces and the command of the military branches. But their information was published in a dry, bureaucratic manner, and what was written had to be compared with the map. This is exactly what analysts like the aforementioned Tom Cooper did.

Below is a screenshot of one of the messages from the Armed Forces of Ukraine. We, like many Ukrainians, are grateful to the army even for such dry messages. Their honesty gave the feeling that although the situation was difficult, chaos had been avoided. However, this objective information drowned in the general flow of other contradictory messages from civil authorities, official speakers and unofficial advisers of the President’s Office. The civilian authorities were unable to take the message of the military as a basis and convey it widely to the people.

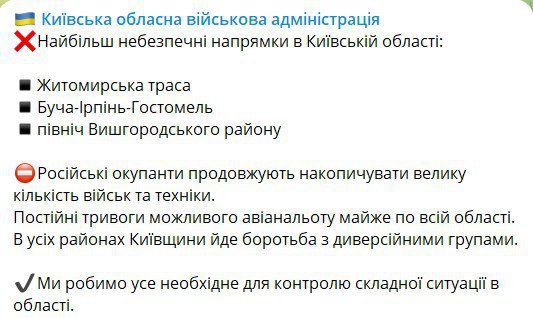

At the beginning of March, the Kyiv Regional Military Administration was informed about the danger. Here is a message on the administration's Telegram channel from March 3. Although similar messages on their resources were not regular and were lost in the stream of other information.

Screenshot 2023-02-15 211319.jpg

The screenshot says:

Kyiv State Military Administration

The most dangerous directions in the Kyiv Region:

- Zhytomyr Highway

- Bucha-Irpin-Hostomel

- North of the Vyshhorod District

The Russian occupiers continue to accumulate a large number of troops and vehicles.

Constant warnings of possible air attacks almost everywhere in the region.

All districts of the Kyiv Region are continuing to fight the sabotage groups.

We are doing everything necessary to control the difficult situation in the region.

"Russian troops will not enter Bucha"

The information released by state organizations in the first days of the war was fragmentary and did not give an accurate idea of what was happening on the spot. In addition, it did not contain clear recommendations to the civilian population on what to do. On top of that, the situation with communication and the Internet worsened. All these factors resulted in "Brownian motion" in the Kyiv region among the civilian population at the end of February and the beginning of March - some managed to get out of the occupied territories somehow, while others went towards the occupiers.

"Immediately after the invasion, we decided to go with our family from Kyiv to our country house in the Makariv district, because we thought it would be quieter there," says Andriy, a resident of Kyiv. “At first, everything looked like that. From the side of Hostomel, the sounds of the battle were heard, but it was quiet in our place. From the television news, it was as if there was nothing threatening us. We planned to stay there for a long time. But at some point, relatives from the north of Zhytomyr region started calling us and telling us that Russian troops were coming our way from Belarus. Honestly, I didn't really believe in it, but in the end, we decided to go to Zhytomyr for a few days just in case. We left in the evening, and the Russians entered the village the very next morning."

We will quote the director of the club in Moschun, Iryna Gertner, about whom we have already written. She remembers almost hourly everything that happened in the first days of the war:

"We woke up, like everyone else, at 5:00 a.m. from the explosions. We could already see the fire coming from the side of the Vyshhorod district. Soon enough, the explosions became closer, so my family and I went down to the basement. Already around noon, we saw huge, dark green helicopters over our houses.

At first, we could not understand who they belonged to, and then we saw that they were flying towards the Hostomel airport. Then we watched explosions and smoke literally from our windows. Now I understand why people in Hostomel, Bucha and Irpin stayed and did not leave. Because the official information was just like that and people just followed it. But the next day it became known that the bridges in Bucha and Irpin were being blown up."

In the north of the Kyiv region at the beginning of March, the situation was approximately as follows: part of the region was already occupied, and battles were raging in the remaining part. Additionally, people were constantly trying to escape - some succeeded, while others died from Russian bullets. In some parts, the authorities organized an evacuation, and in the places of brutal fighting, people mostly had to take care of themselves, and they were assisted in this by the Territorial Defense, Ukrainian military, local activists and regular people who just wanted to be helpful.

Of course, local authorities were also responsible for evacuation and informing the population. Let's not forget that the government decree from 2013 clearly prescribed the creation and functions of evacuation commissions under local authorities. Provisions were made for informing the population and taking them to safe regions in case of dangerous situations, including armed conflict. Somewhere these commissions really worked, while elsewhere they only existed on paper due to inactivity of the authorities or "insurmountable circumstances".

For example, the mayor of Bucha, Anatoliy Fedoruk, according to his own words, had to go underground during the occupation of the city by the Russians, so he could not properly inform the residents of the town. It was the lack of public information and evacuation actions that some townspeople blamed on him. But the mayor claims that the local government did not receive objective information from the state administration. "We were interested to know how we should act. The regional and district leadership said that Russian troops would not enter Bucha," says Fedoruk.

In general, one simple comparison suggests itself to this whole situation. During peacetime in a peaceful country, any random enterprise where the management cares about the safety of its employees regularly organizes training drills for the evacuation of personnel in the event of a fire or any other man-made disaster.

One can wonder what prevented the country’s leadership, as well as relevant departments and local authorities from carrying out similar measures: preparing the population, developing appropriate information tools in conditions when Ukraine's allies kept warning us about the impending threat? But the answer is known: the authorities in Kyiv did not believe the invasion would happen. So, as we can see, there were no plans in case of an attack and the country was saved "as the play progressed".

We also understand that optimistic statements were needed so that the state would not be engulfed in an avalanche of real panic, when all authorities collapse and no one resists. But the question of whether it was expedient to maintain the general morale at the expense of thousands of civilians who were trapped because of trust in official reports remains open.