Velykyi Luh: Map of the Great Meadow

Land of Ukrainian Cossack State, the Mongol Khan's headquarters and more

Velykyi Luh:

Map of the Great Meadow

Land of Ukrainian Cossack State, the Mongol Khan's headquarters and more

Читати українською

Velykyi Luh, meaning “Great Meadow”, is one of the most important natural and historical landscapes in Ukraine. Not only was this region once the cradle of Ukrainian statehood, but it also contained a colossal amount of historical and archaeological landmarks, along with many rare animals and plants.

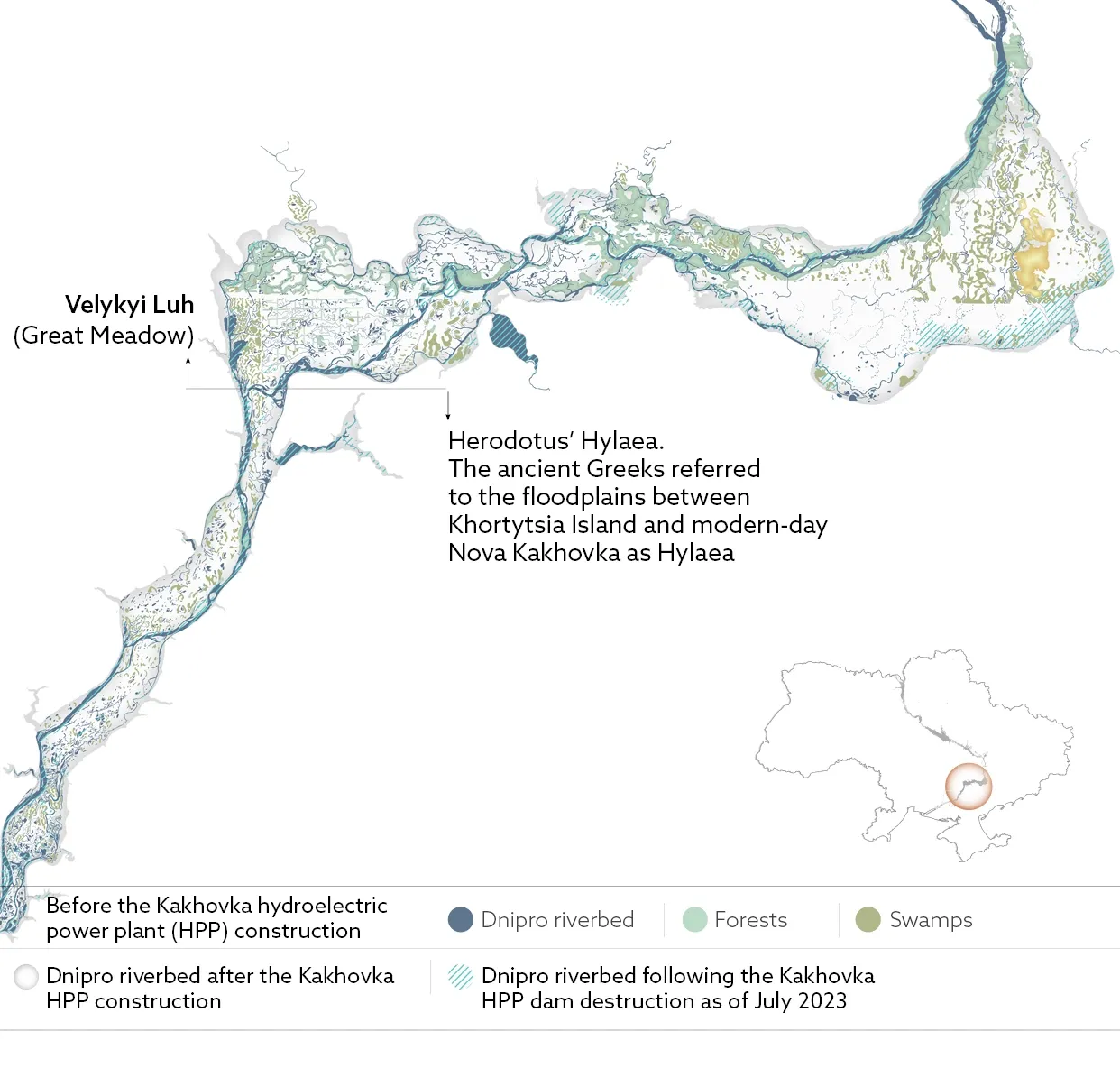

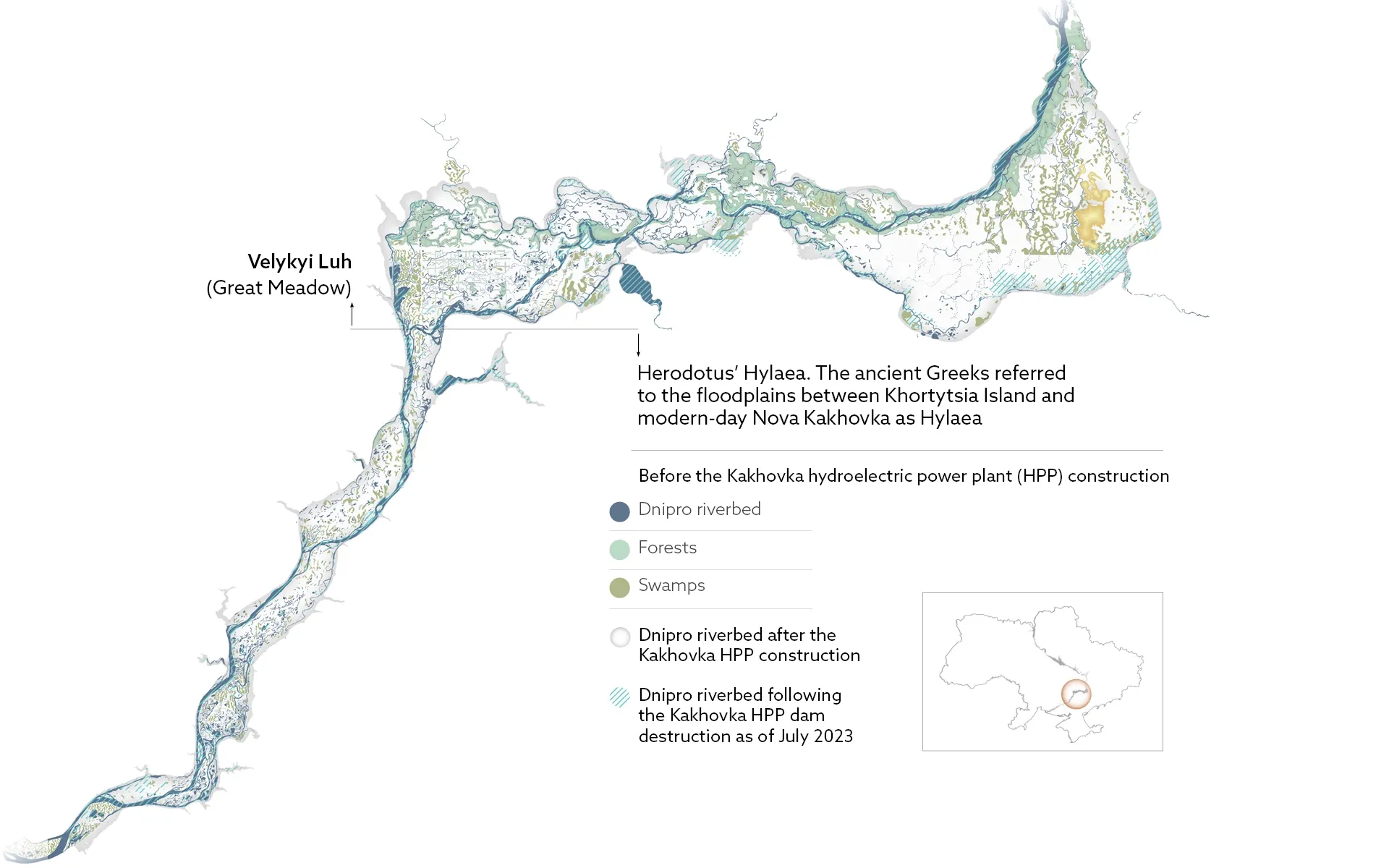

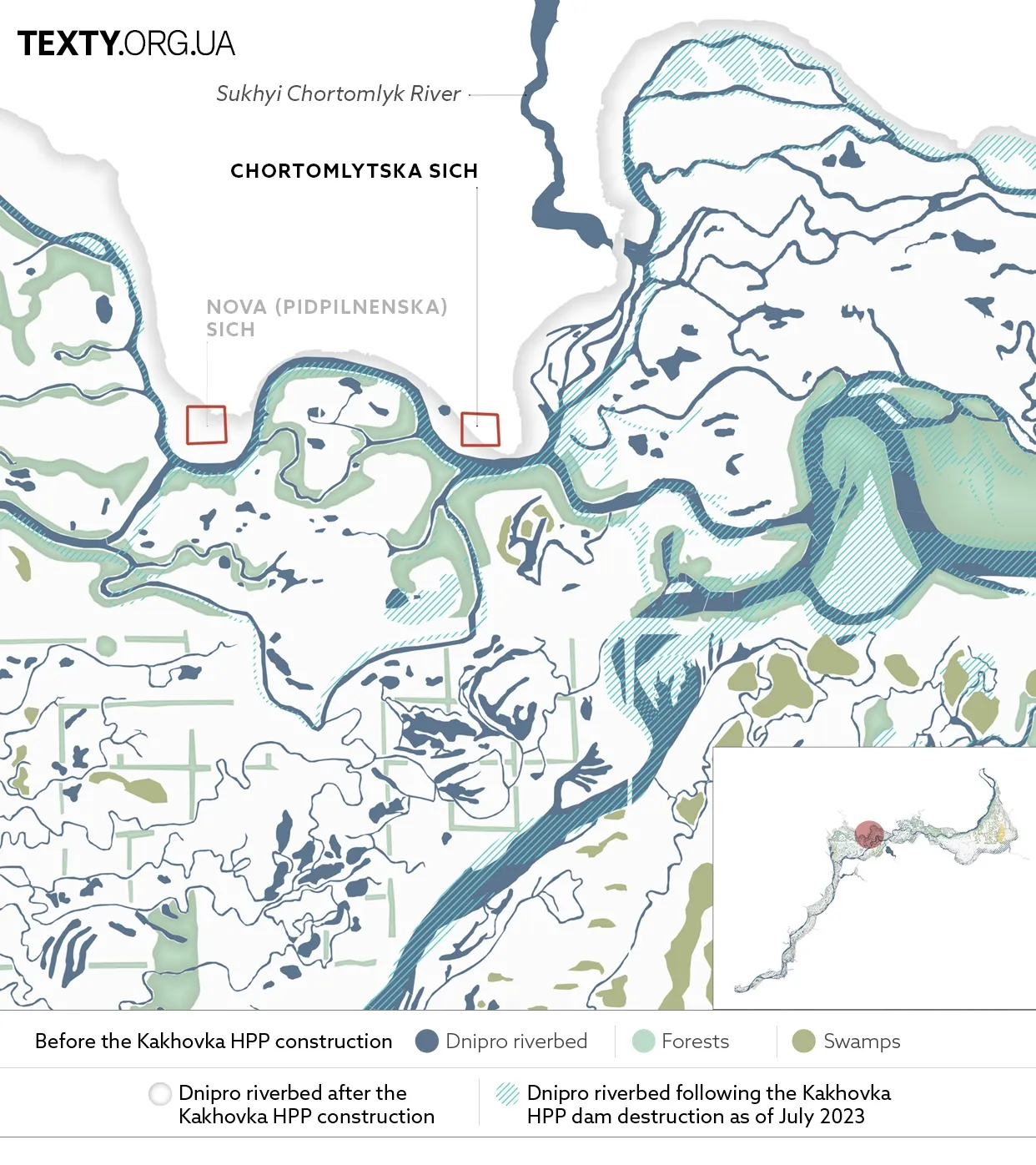

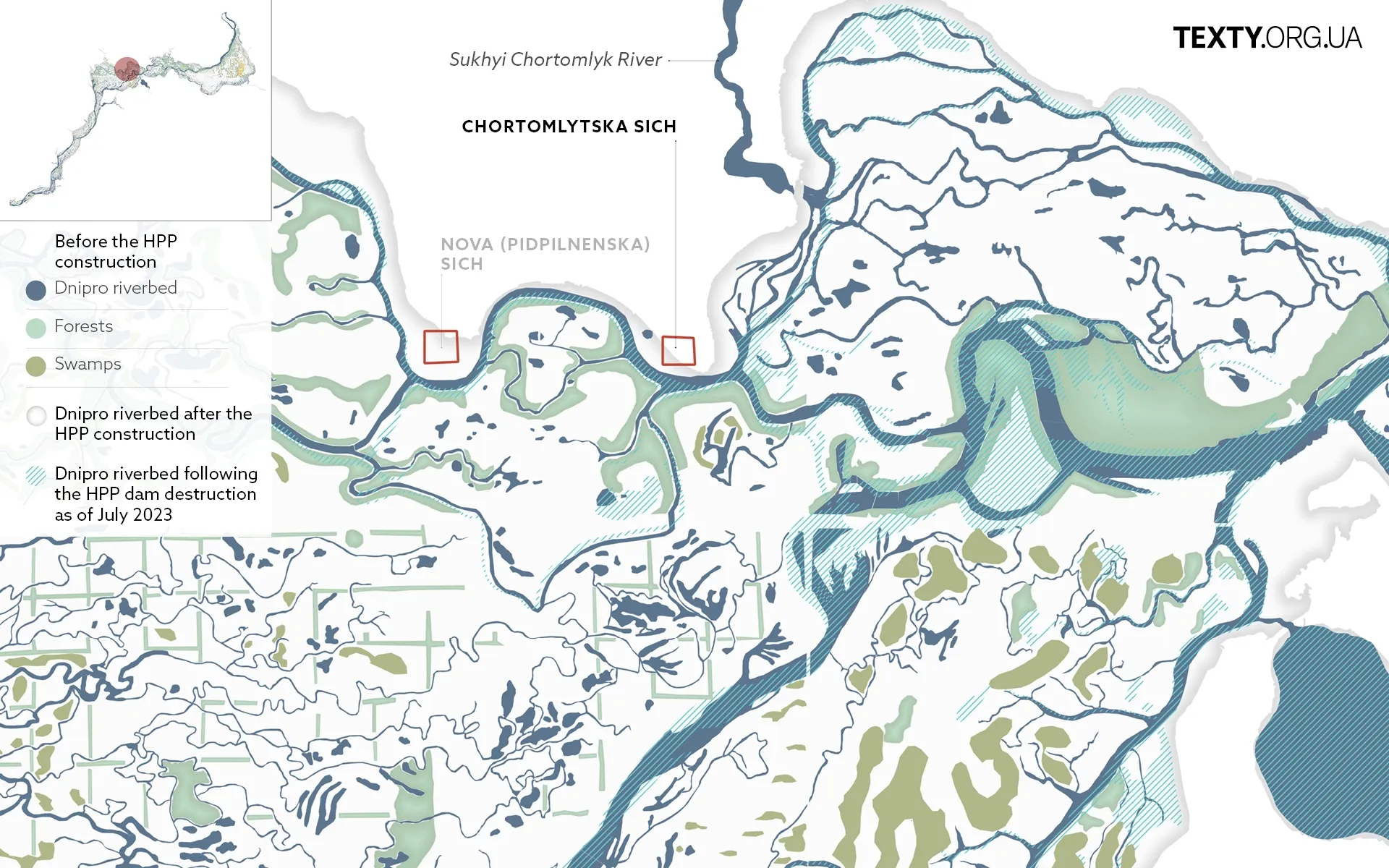

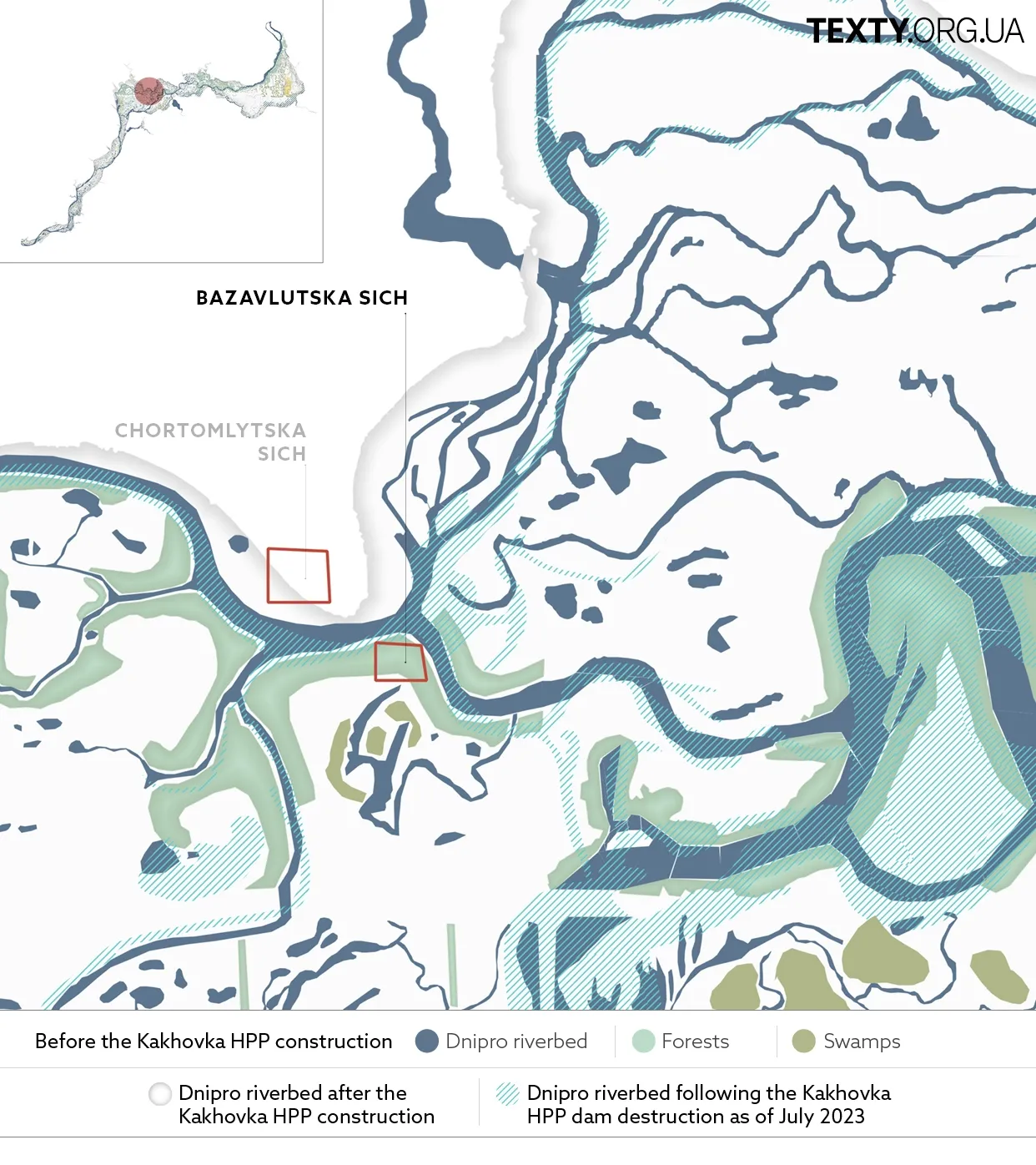

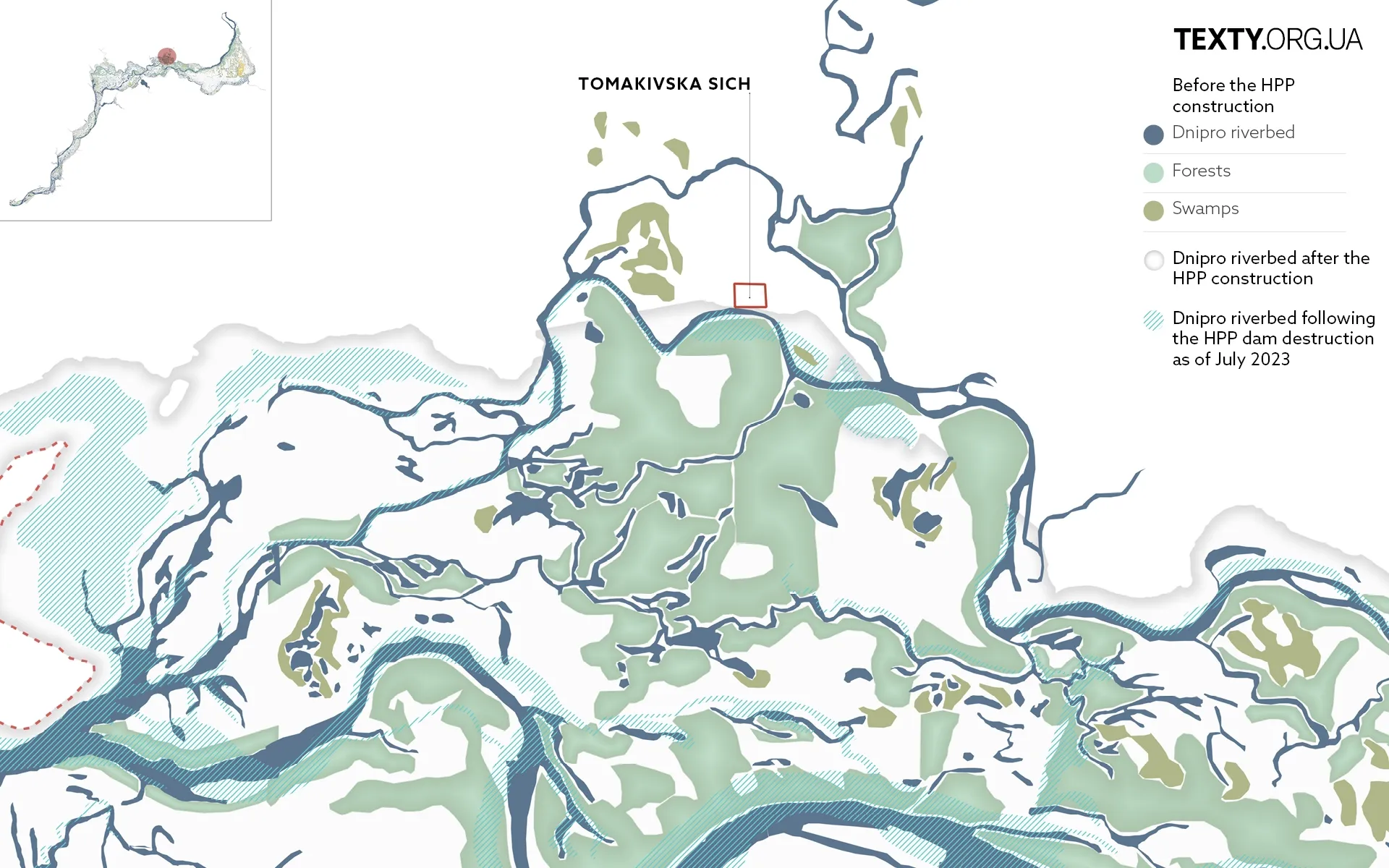

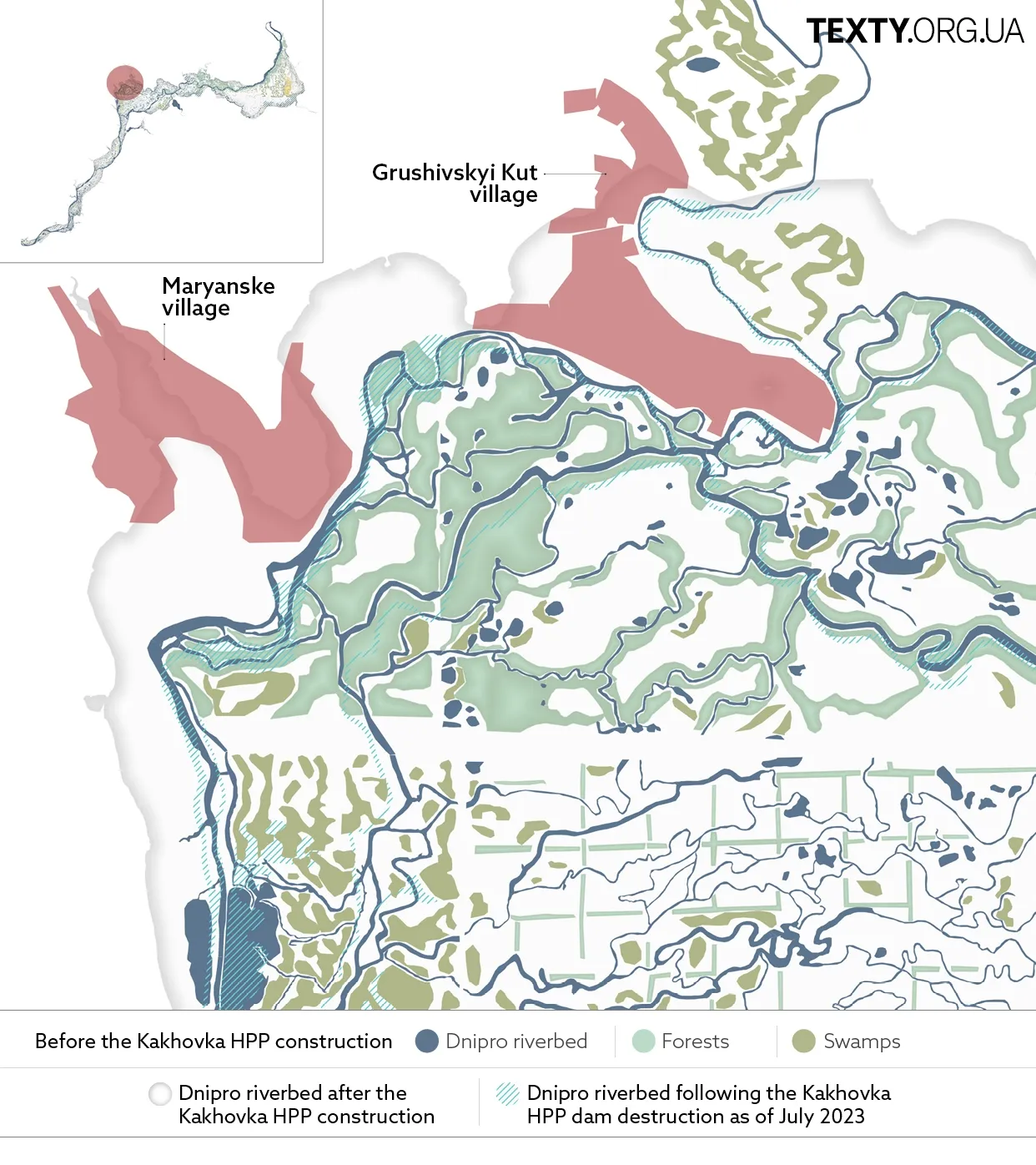

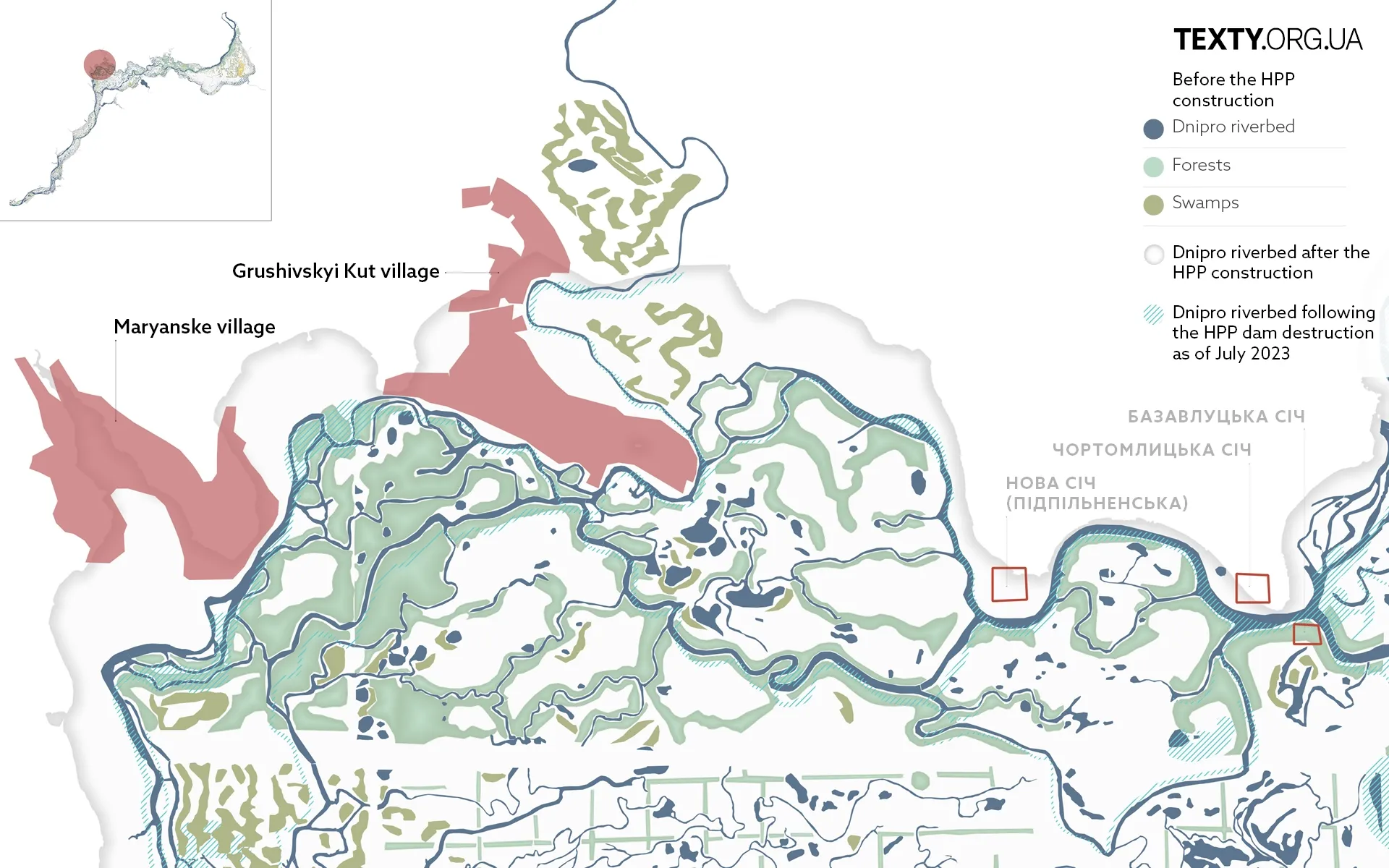

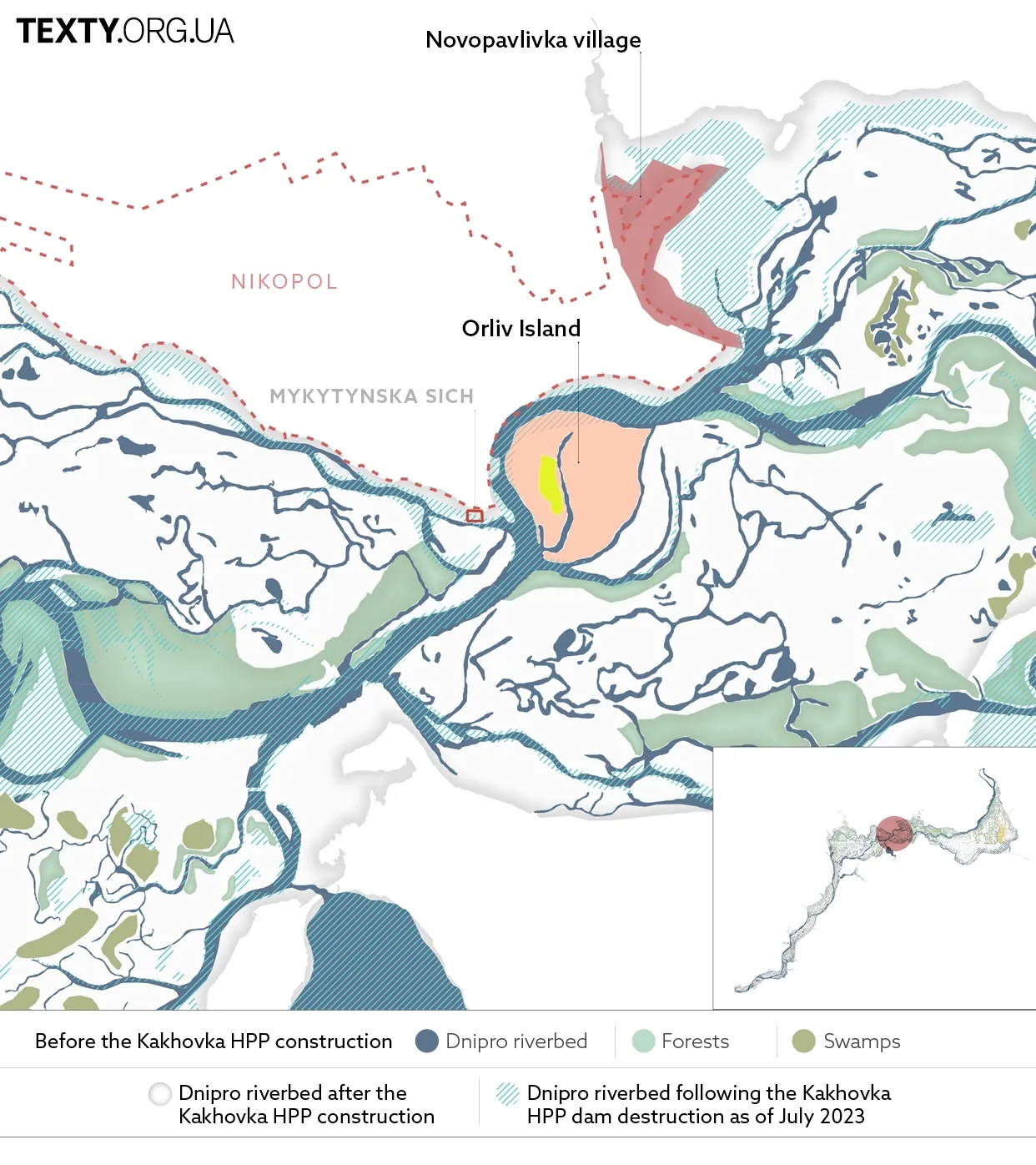

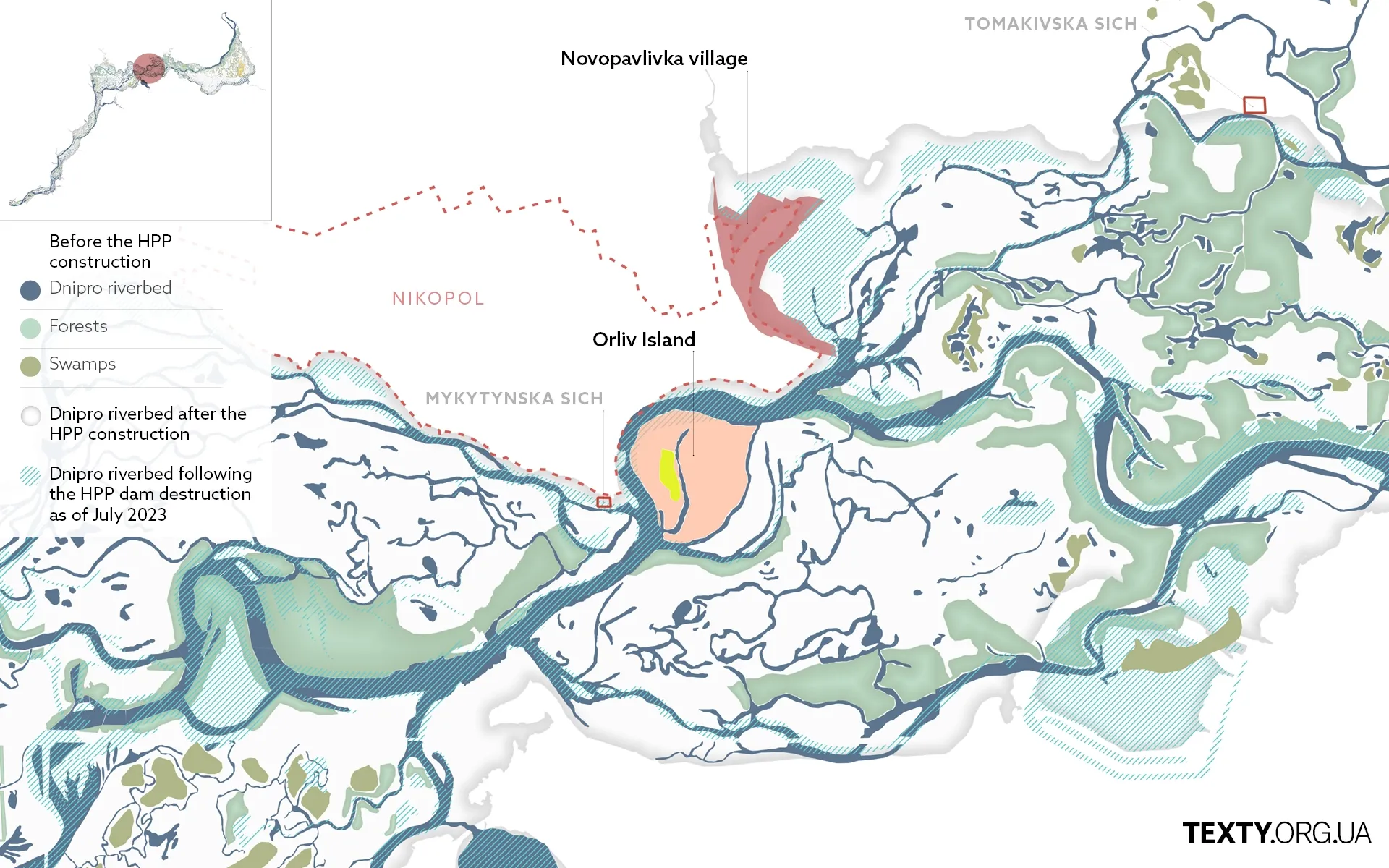

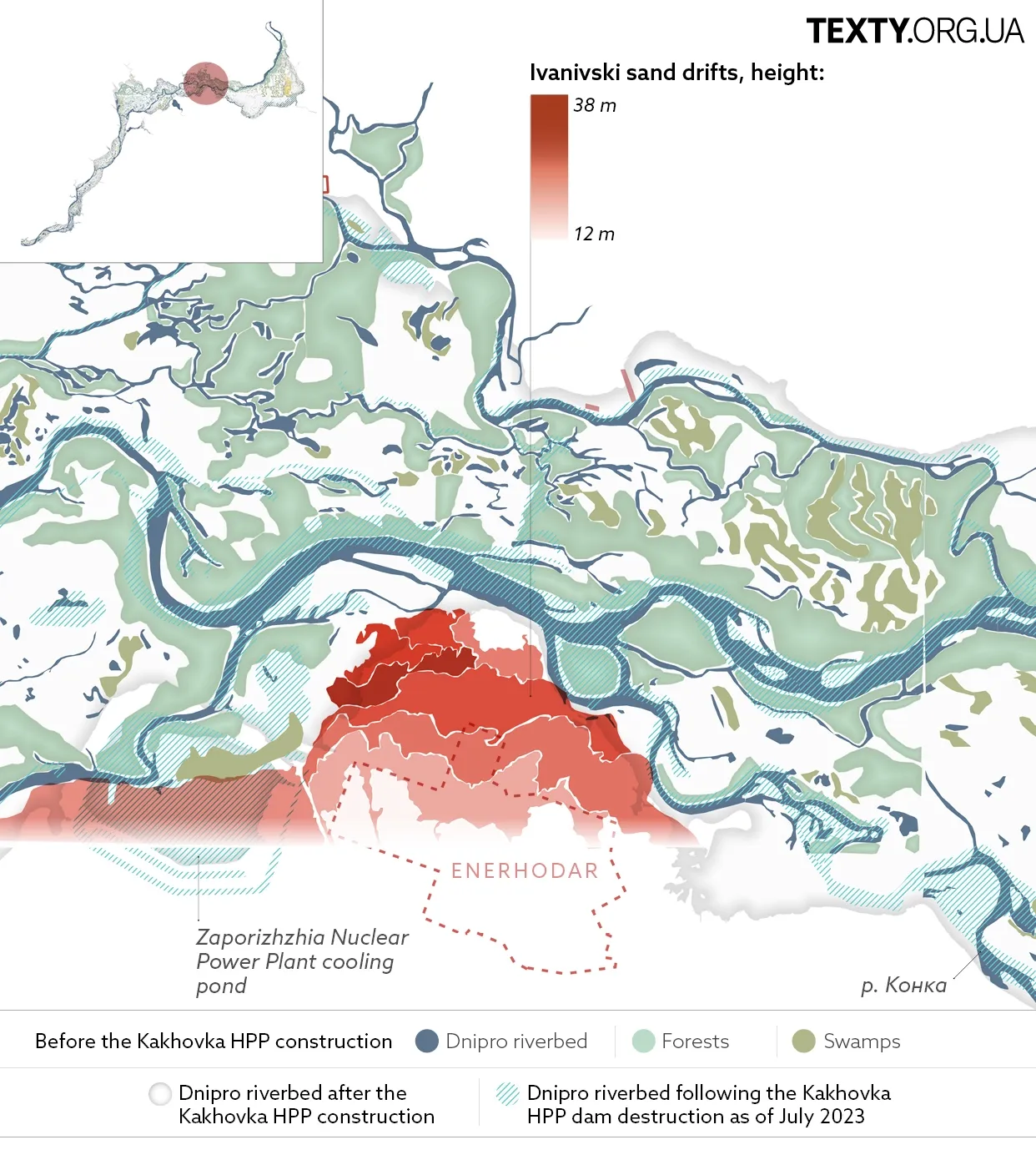

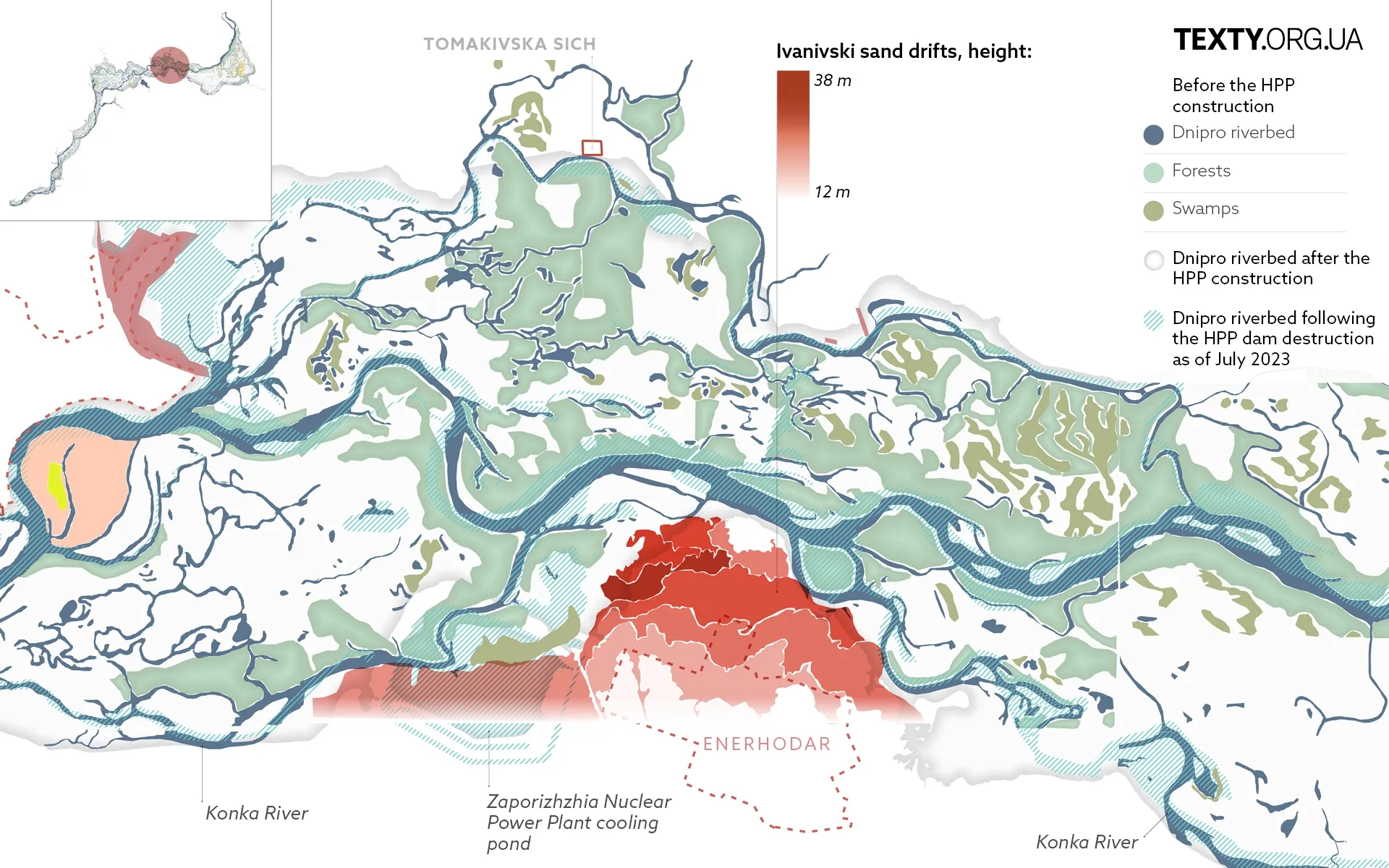

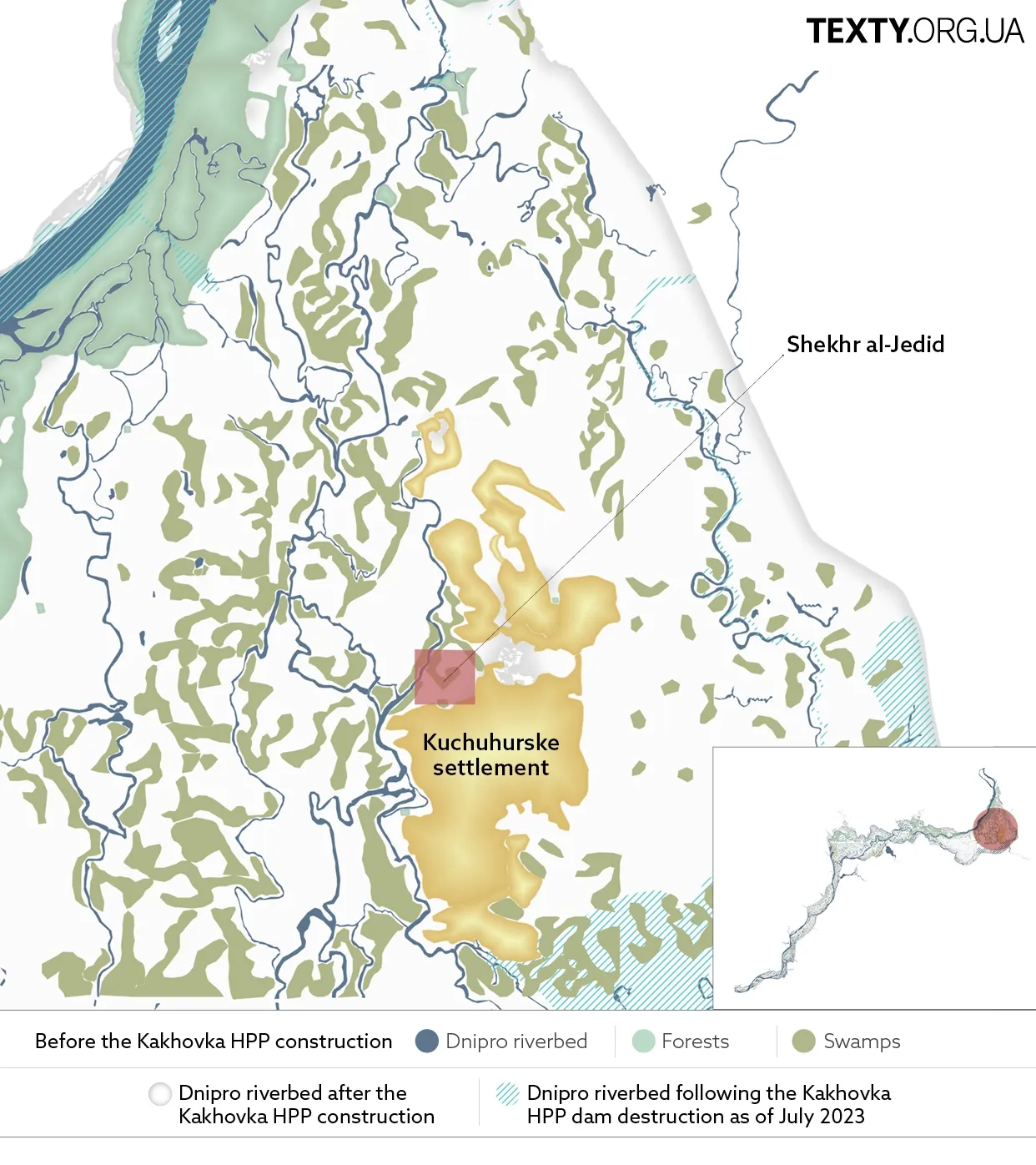

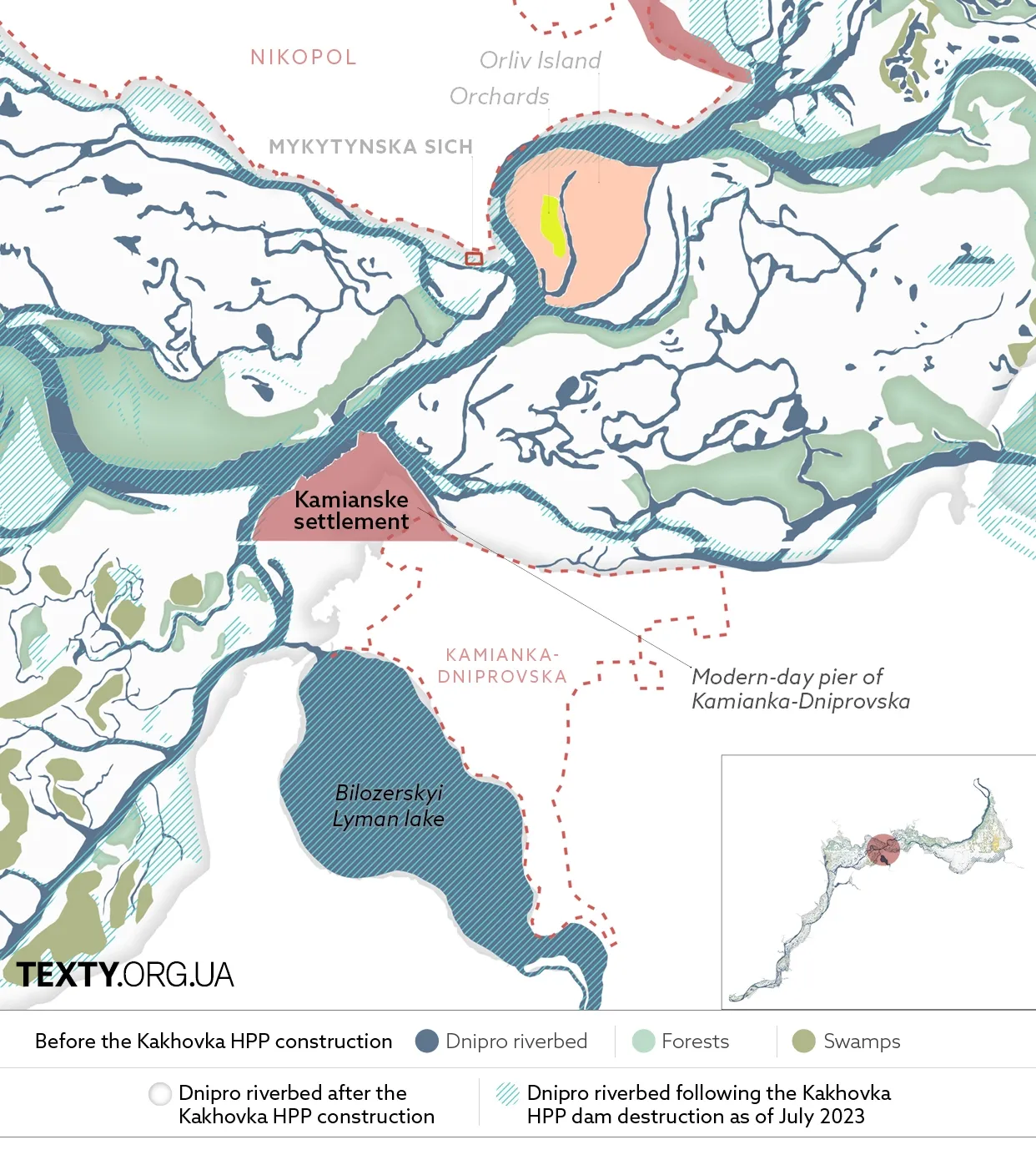

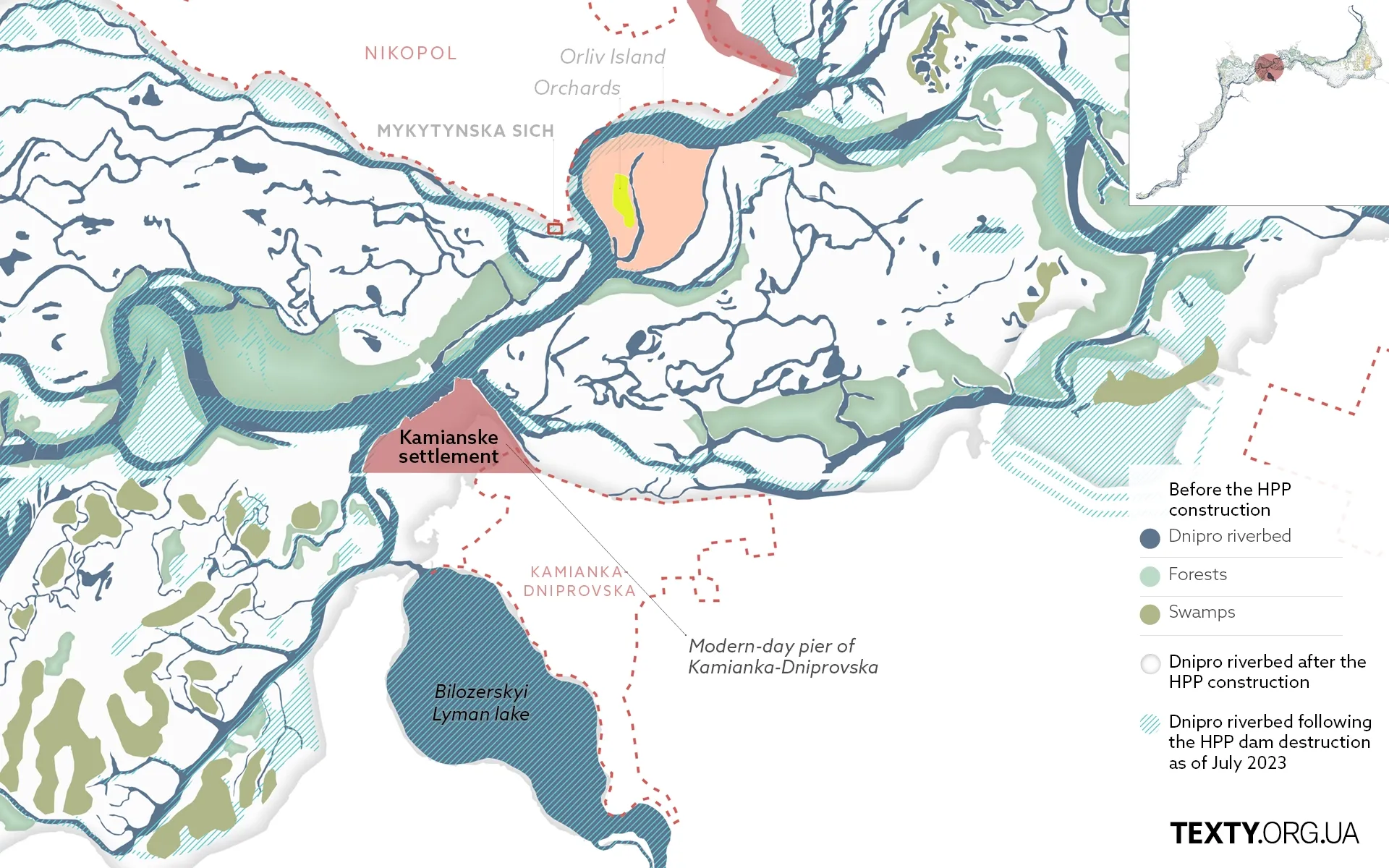

What did Velykyi Luh look like before the area was flooded during the construction of the Kakhovka Reservoir in the 1950s? It's hard to imagine. Texty.org.ua took German topographic maps from the 1940s and superimposed the current Dnipro riverbed on them, which was formed after the Russian forces blew up the Kakhovka dam in June 2023. Against this backdrop, we explore the key historical and simply interesting locations around Velykyi Luh. We used satellite images from July 2023 to analyse the data on the newly formed river channel in this area.

The location of the historical sites was taken from the map of Oleh Vlasov, a junior researcher at the History Department of the Khortytsia National Reserve.

Velykyi Luh

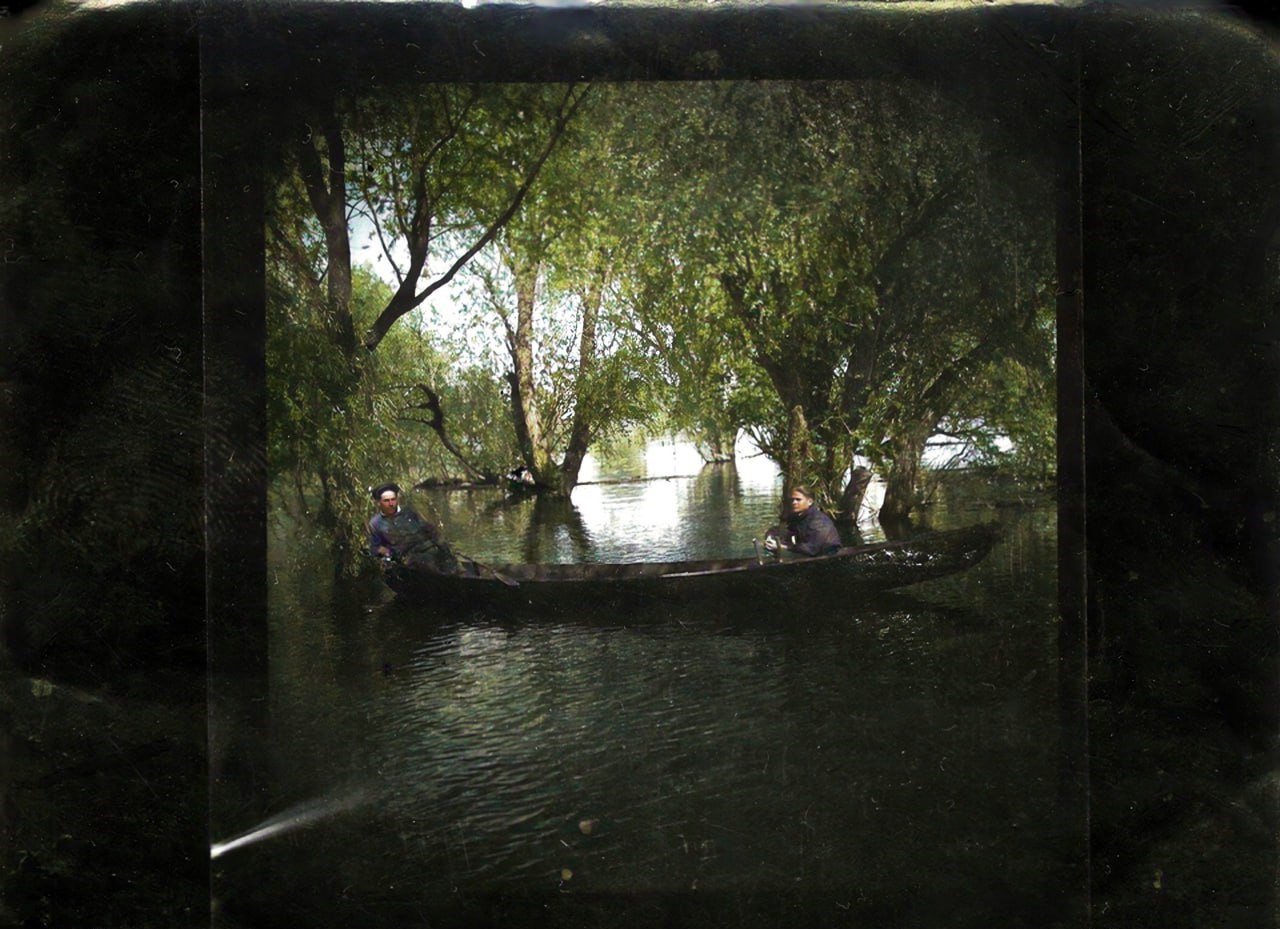

Velykyi Luh consists of interconnected rivers and their numerous tributaries, reed-covered lakes and swamps, meadows, floodplain forests, shrubs, and, in some places, high sandbanks. This landscape was very different from the neighboring steppe terrain. Both the right and left banks of the Dnipro River were covered with numerous trees here.

Velykyi Luh spanned over 100 km (62 miles) from east to west and 20-25 km (12-15 miles) from north to south.

Five of eight Zaporizhzhian Sichs were located in Velykyi Luh in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Sich (Ukrainian: січ) served as an administrative and military centre for the Ukrainian Cossacks. The term originates from the Ukrainian verb meaning “to chop,” carrying the connotation of clearing a forest for a campsite or constructing fortifications using the trees that have been chopped down.

The prominent Ukrainian Cossack leaders Sirko, Vyshnevetskyi, Sahaidachnyi, Doroshenko, Khmelnytskyi, and others used the meadow as their base.

Below Velykyi Luh the famous Herodotus' Hylaea stretched from the village of Babynove in the Kherson region to modern-day Nova Kakhovka. The Gilea was known as the woody region, home to huge trees, predominantly oaks.

More than 250,000 hectares (over 600,000 acres) of land were buried under the waters of the "Kakhovka Sea", including Dnipro floodplains, remnants of the Sich and ancient mounds, numerous villages, forests, swamps, and floodplain islands where people cultivated vegetables on fertile soils. Before the inundation, old and mighty trees were cut down and taken away. Many animals died: not all of them managed to escape the flood; some, including wolves, were deliberately shot down.

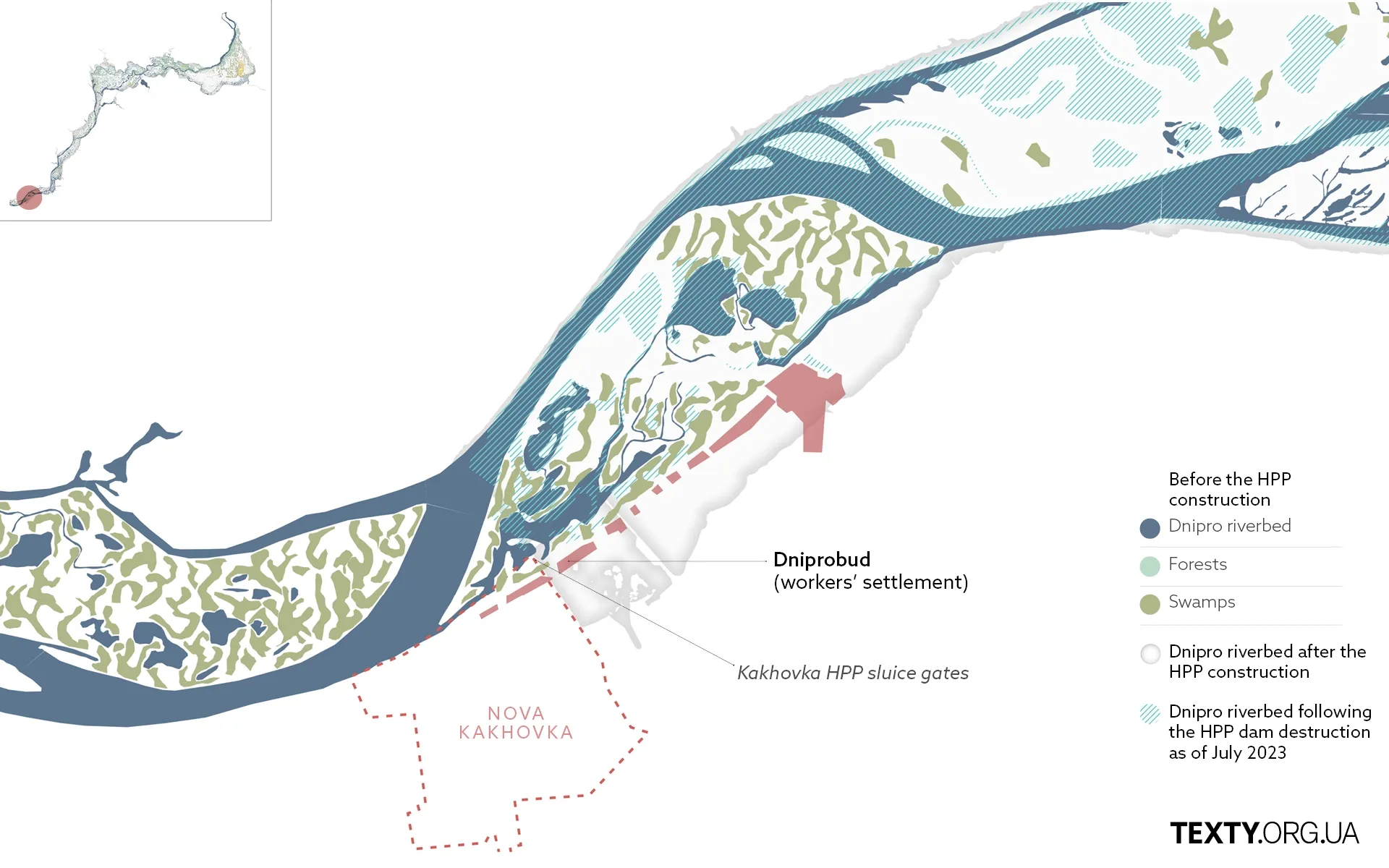

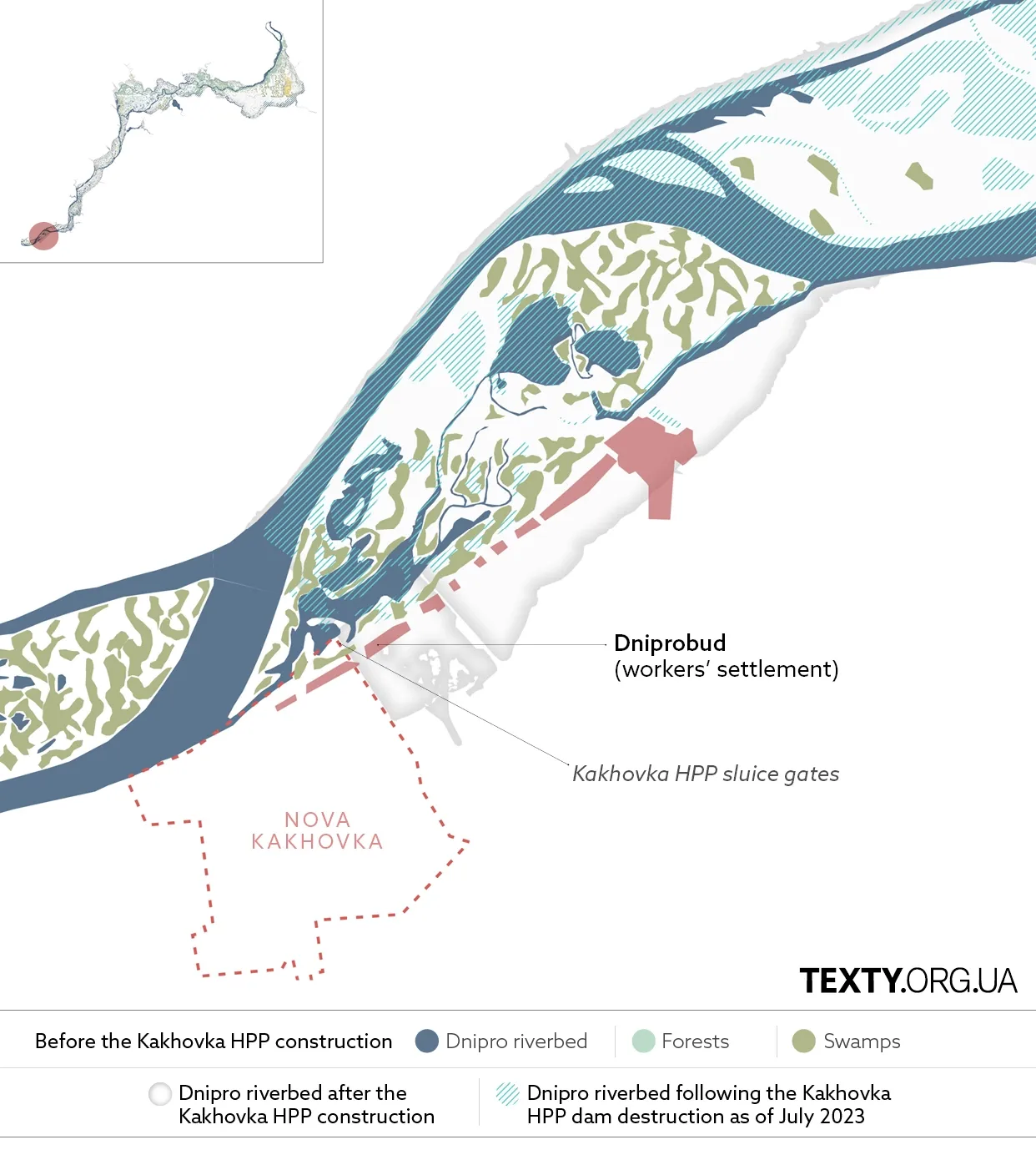

Dniprobud

Dniprobud is a workers' settlement near the Kakhovka hydroelectric power plant gateway within the village of Kliuchove.

Eight months into construction, the living conditions for the construction workers were dire, as described in a letter by the then-prosecutor of the Kherson region:

"There are 1-2 square meters of living space per person. Males and females are accommodated in the same rooms; in most apartments, glass windows are missing, and the window- and door frames are broken. A significant percentage of the workers do not have blankets, pillowcases or bed sheets, and many more do not have beds..."

Simultaneously with the construction of the sluice gates, 1,063 houses were built on the territory of the future Nova Kakhovka. Residents of the surrounding villages whose houses appeared in the flood zone were relocated here.

The memoirs of Oleksandr Dovzhenko, who was present at the construction of the Kakhovka HPP, detail the situation:

"No explanatory work was done. They just went into the yards, measured, recorded, and informed everyone individually about the flooding and the need to relocate. Moreover, everyone who did not have time to move within a certain period was told: ‘If you don't leave before this date, we will bulldoze your house, regardless of whether you still live here or not.’ People were forced to comply."

On June 10, the first barges passed through the lock, and at the end of the month, the steamer ‘Kommunist’ sailed through with all the pomp and significance.

In 1957, 4,000 workers from the Dniprobud department left to build a new hydroelectric power plant in Dniprodzerzhynsk. The remaining 12,000 workers stayed in Nova Kakhovka.

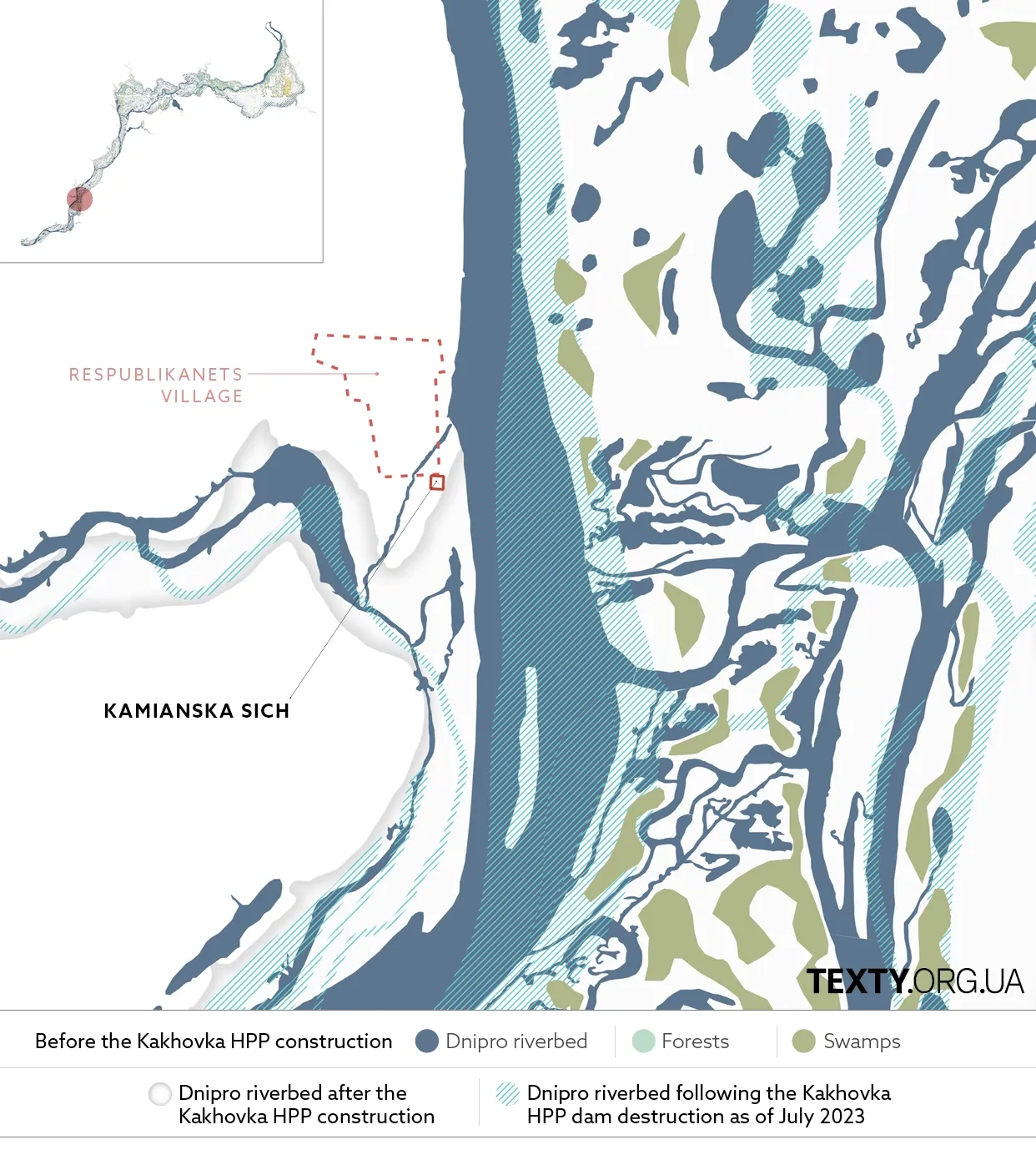

Kamianska Sich

Kamianska (Stone) Sich, a former Ukrainian Cossack outpost, was active in 1709-1711 and 1728-1734. The remains of the Kamianska Sich are now located near the village of Respublikanets (The Republican) in the Kherson region.

The Kamianska Sich is the only Sich where some objects of historical importance have been preserved: the council square,the treasury, a craft workshops, Cossack dwellings, shops, and a tavern. One of the famous Cossack leaders, Kost Hordiienko, who spent his life opposing Peter the Great and the Muscovites, was buried at the Kamianska Sich cemetery.

The remnants of Kamianska Sich have been eroded over decades due to the impact of the Kakhovka Reservoir.

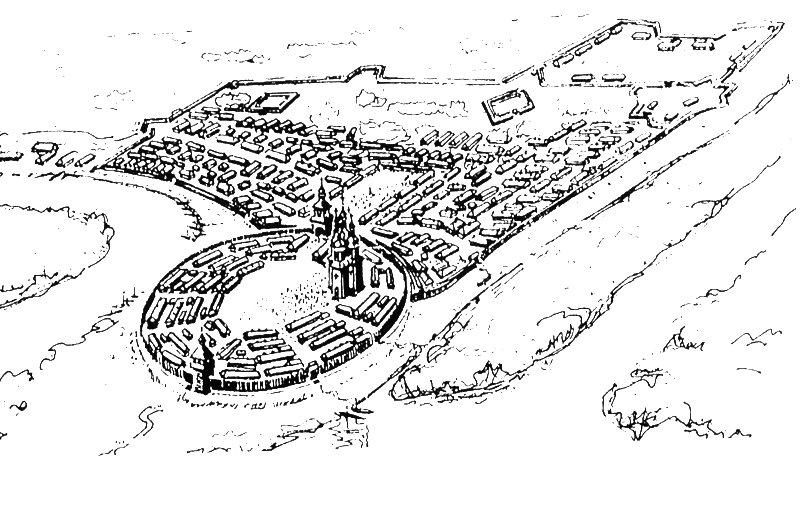

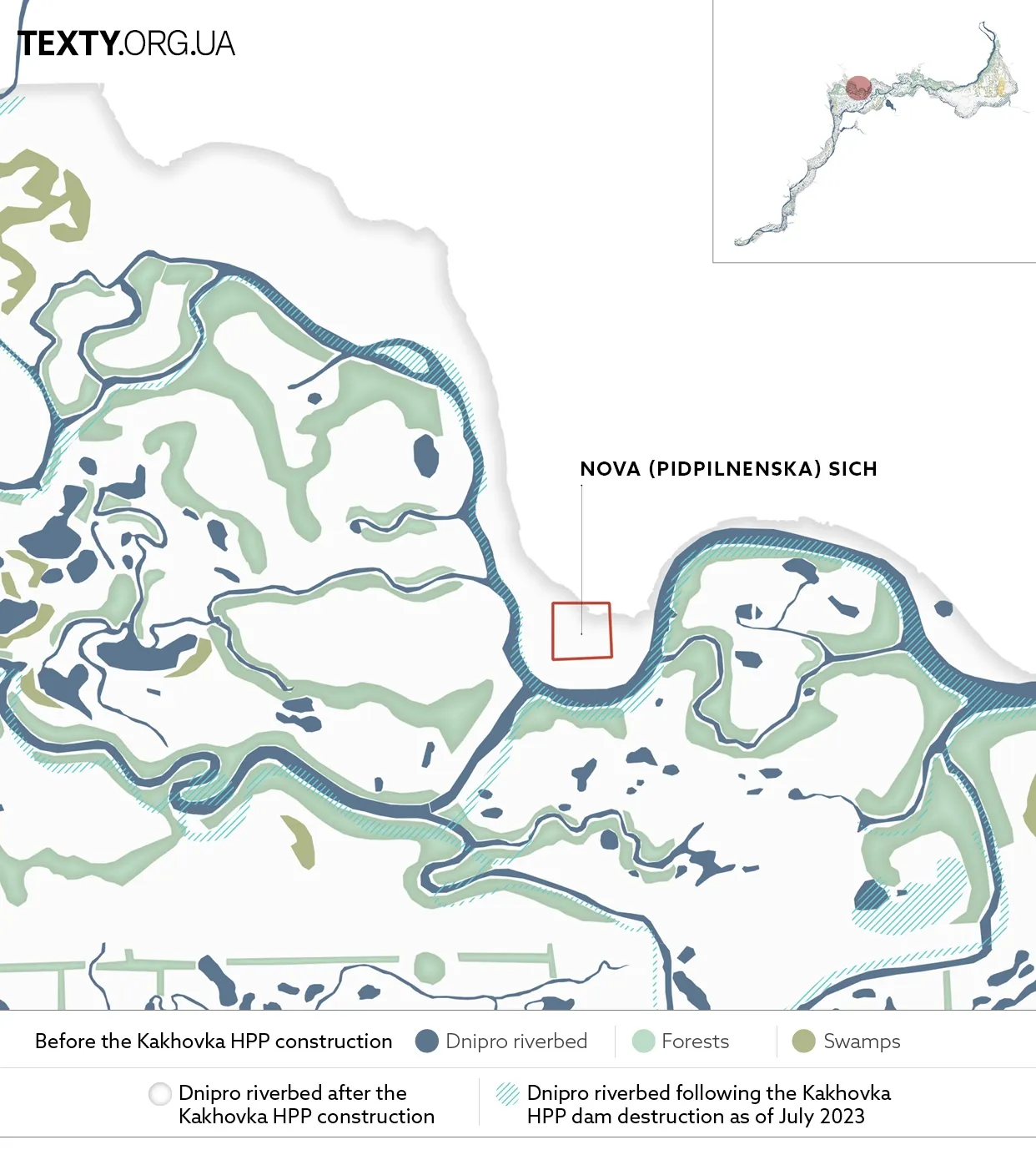

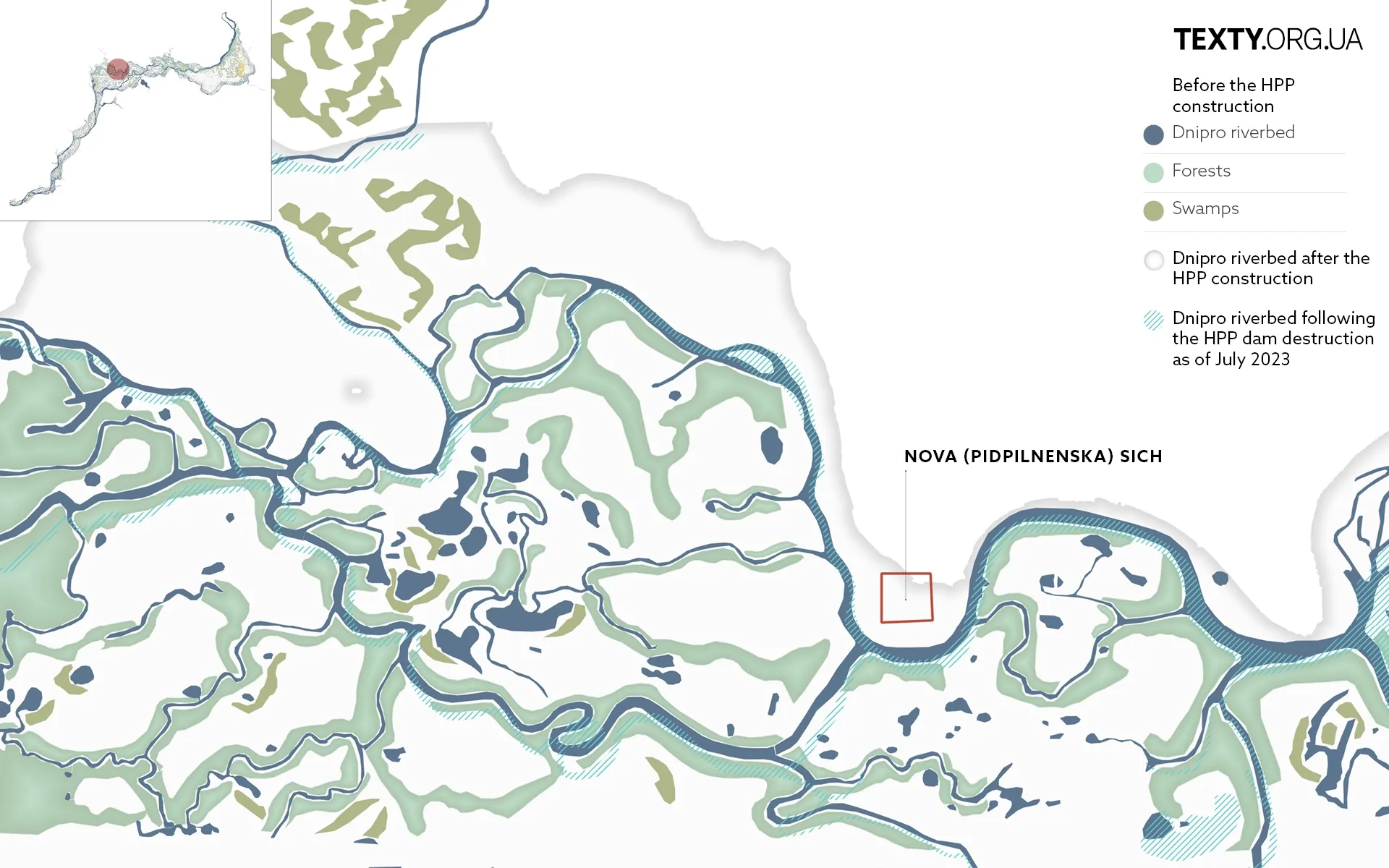

Nova (Pidpilnenska) Sich

Nova (New) / Pidpilnenska (Сlandestine) Sich was the last Sich, established on the right bank of the Dnipro River with the imperial permission by hetman-otaman Ivan Malashevych in 1734. Positioned on a large peninsula surrounded by the Pidpilna River, a tributary of the Dnipro, it was within 2 km of a Russian outpost set up to monitor the Cossack activities.

During its heyday, Nova Sich was a fortress with an earthen rampart 3.5–4 m high, topped with rows of oak stakes and observation towers. The fortifications were surrounded by a deep moat filled with water. Zaporizhian Cossack assemblies were held in the Sich square (maidan), where one could also find the leader's residence, treasuries, chancellery, rows of kurins (Kurin (Ukrainian: курінь) is a type of a temporary housing used by the Cossacks, usually in a form of a tent or a wooden house), and the Church of the Intercession of the Holy Virgin.

The Sich was built in the middle of low-lying floodplains that stretched for tens of kilometres around. The area was impassable for enemies due to the dense forests intersected by a network of numerous swamps, bays, lakes and rivers. For those unfamiliar with the area, navigating through it felt like a labyrinth.

In June 1775, Catherine II ordered the demolition of the Nova Sich. In its place, the Cossacks established the village of Pokrovske, which was partially inundated in the 1950s.

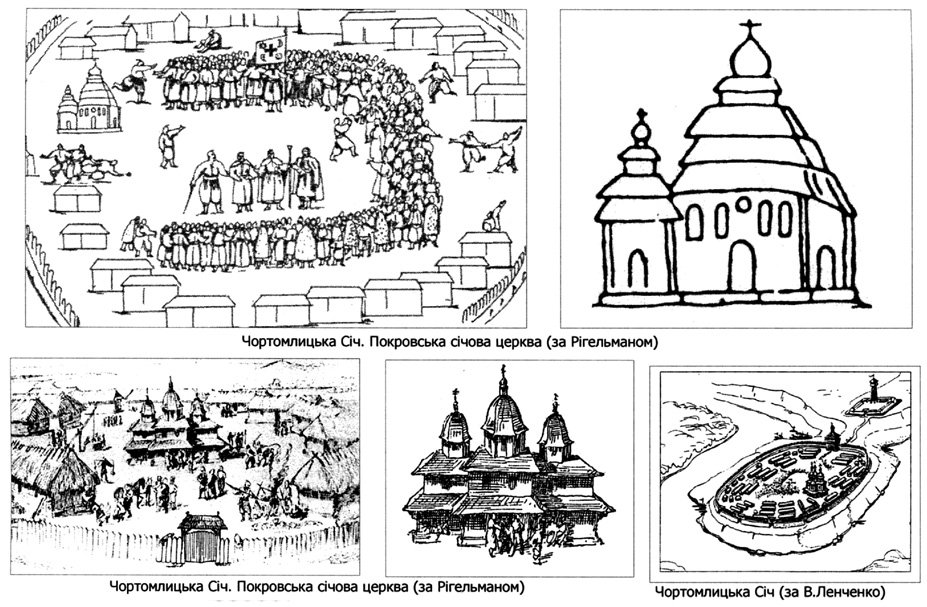

Chortomlytska Sich

Chortomlytska Sich, named after the Chortomlyk River, is also known as the Old Sich (1652-1709). It was located on the Chortomlyk Cape. It gained prominence during the time of Ivan Sirko, who resided exclusively here from 1663 and was elected otaman more than 15 times. In 1676, Sirko's army defeated a 60,000-strong Turkish-Tatar army that unexpectedly attacked the Sich. The same year, Sirko's Cossacks forced their way across the Syvash and conquered the khan's capital, Bakhchisarai.

The Chortomlytska Sich was destroyed by the order of Peter the Great following the Cossacks’ alignment with Ivan Mazepa.

Cartographer Guillaume de Beauplan describes Chortomlytska Sich as follows:

"A little below the river Chortomlyk, almost in the middle of the Dnipro, there is a rather large island with ancient ruins, encircled by more than 10,000 islands scattered irregularly... These numerous islands serve as a refuge for the Cossacks, who consider them a military treasury."

Huts with windows overlooking the square stood in the centre of the Sich. Outside the fortifications was the so-called Greek house designated for hosting foreign ambassadors. In the middle was the Church of the Intercession of the Virgin Mary.

In their memoirs, the elders from the neighbouring villages describe the area with the remnants of Chortomlytska Sich as it existed before being submerged by the Kakhovka Sea:

"From the Cossack cemetery near the village of Kapulivka, this place looks like an island amidst the lush green trees, as if floating between eight rivers. Further on, vast plains covered with grass and forests unfold. This forest stretches for 15 kilometres from north to south. Here, nestled in the middle of the trees at the convergence of eight rivers, lies a picturesque island where the glorious Chortomlytska Sich was located."

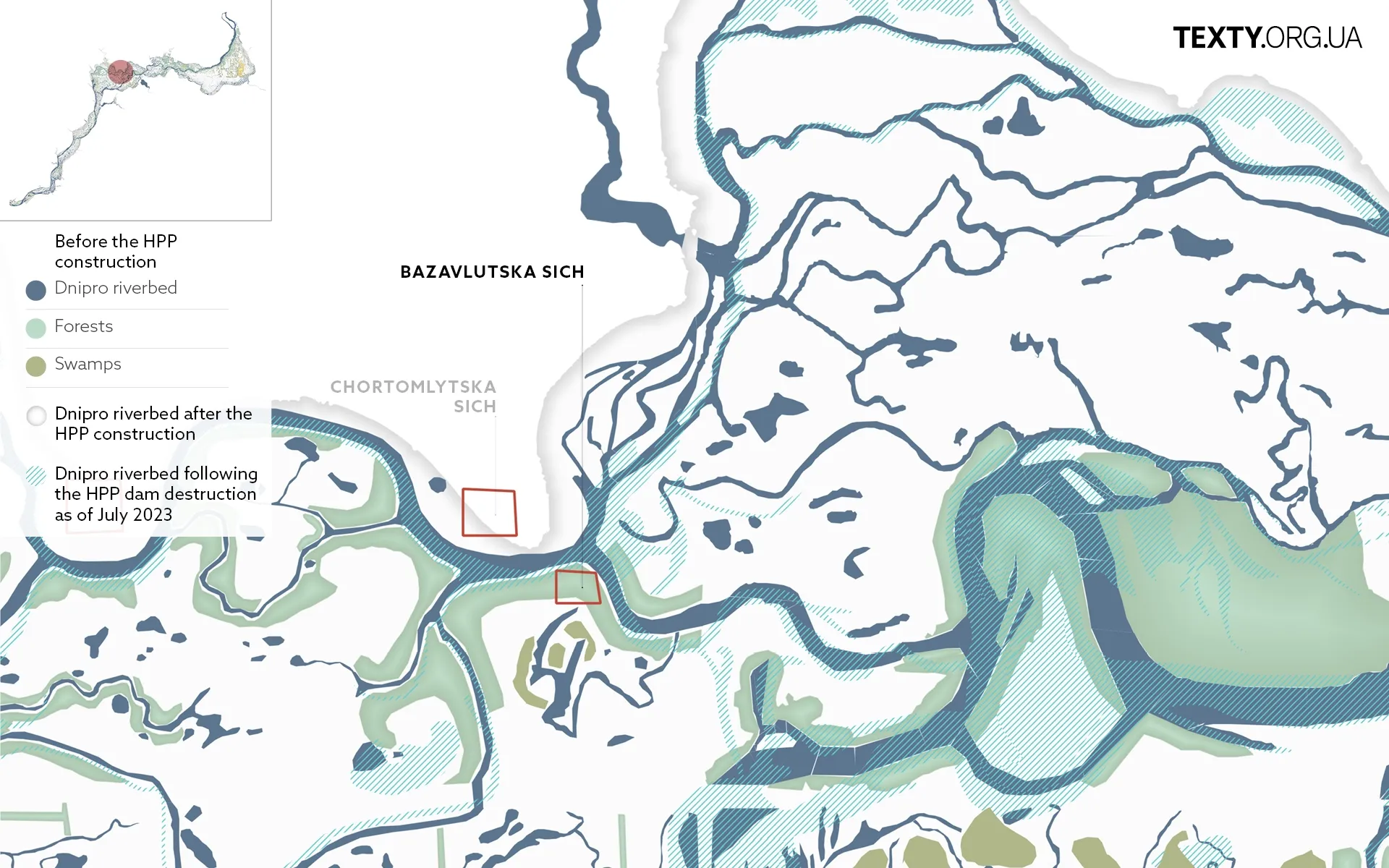

Bazavlutska Sich

Situated on the Bazavluk island, Bazavlutska Sich served as the centre of the Cossack State from 1593 to 1638. It was a large military base, housing a fleet and artillery and serving as the strategic planning ground for naval and land campaigns. The most successful of them were led by the Cossack leaders Petro Sahaidachnyi and Mykhailo Doroshenko.

Bazavlutska Sich was surrounded by thick forests and water bodies adorned with dense reeds, which presented a significant challenge for the Tatars to approach the Cossack fortifications with cavalry. As for the Turkish galleys, they were quicky destroyed by the Cossacks who were able to navigate the intricate river webs with ease.

In the summer of 1638, Bazavlutska Sich met its demise at the hands of the troops led by the Polish Hetman Mikołaj Potocki.

The site bearing the remains of these Cossack fortifications was subsequently engulfed by the Kakhovka Sea waters.

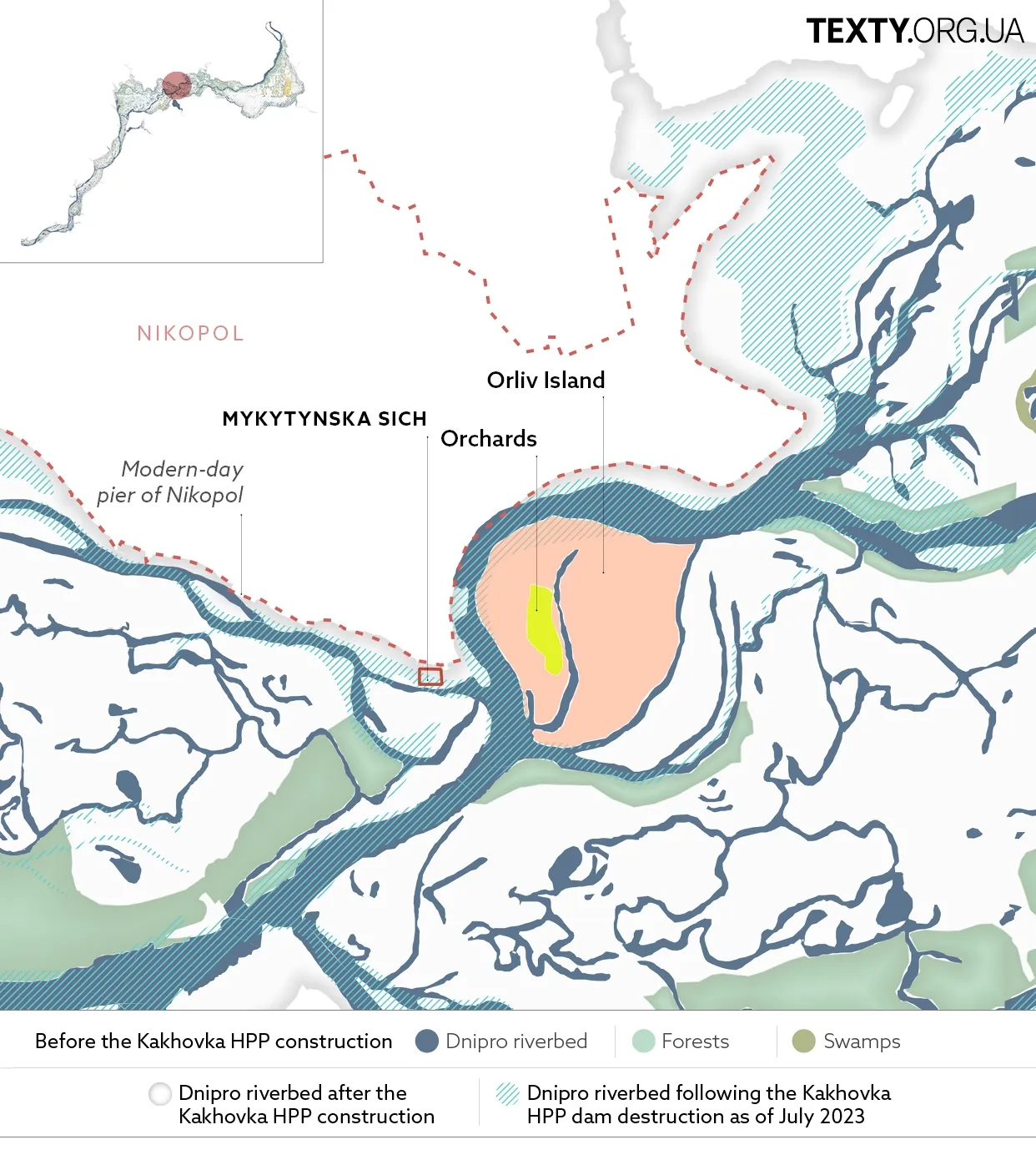

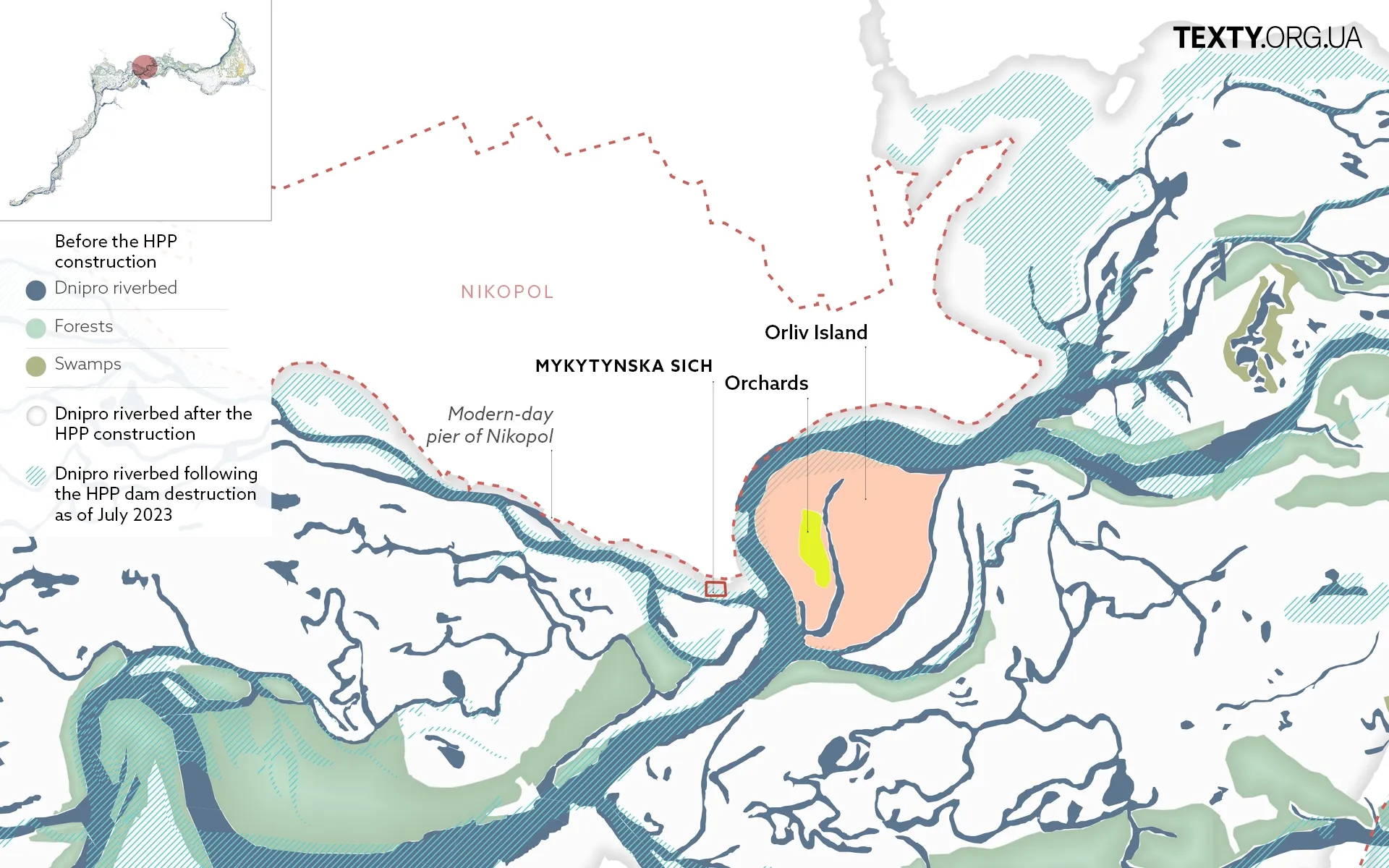

Mykytynska Sich

Mykytynska Sich was built on Cape Mykytyn Rih (Mykyta’s Horn) near Orliv Island (The Eagle’s Island). The Cossacks founded it under the leadership of the Cossack otaman Fedir Lynchay. It was from here that Bohdan Khmelnytsky led the Cossacks to war with the Poles in the mid-17th century.

Today, only memories remain of the Mykytynska Sich. The fortifications, along with the huts, a chapel and a cemetery, were washed away by a stormy stream. The location could only be traced through the testimonies of the residents. According to legend, the Cossack settlement was located about 750 metres downstream from the modern-day Nikopol pier on the right bank of the Dnipro River.

The riverbank itself would erode every year, exposing rotten coffins from the ancient cemetery. Buttons, icons, crosses, and liquor bottles, which were considered essential for a Cossack in the afterlife, were discovered here.

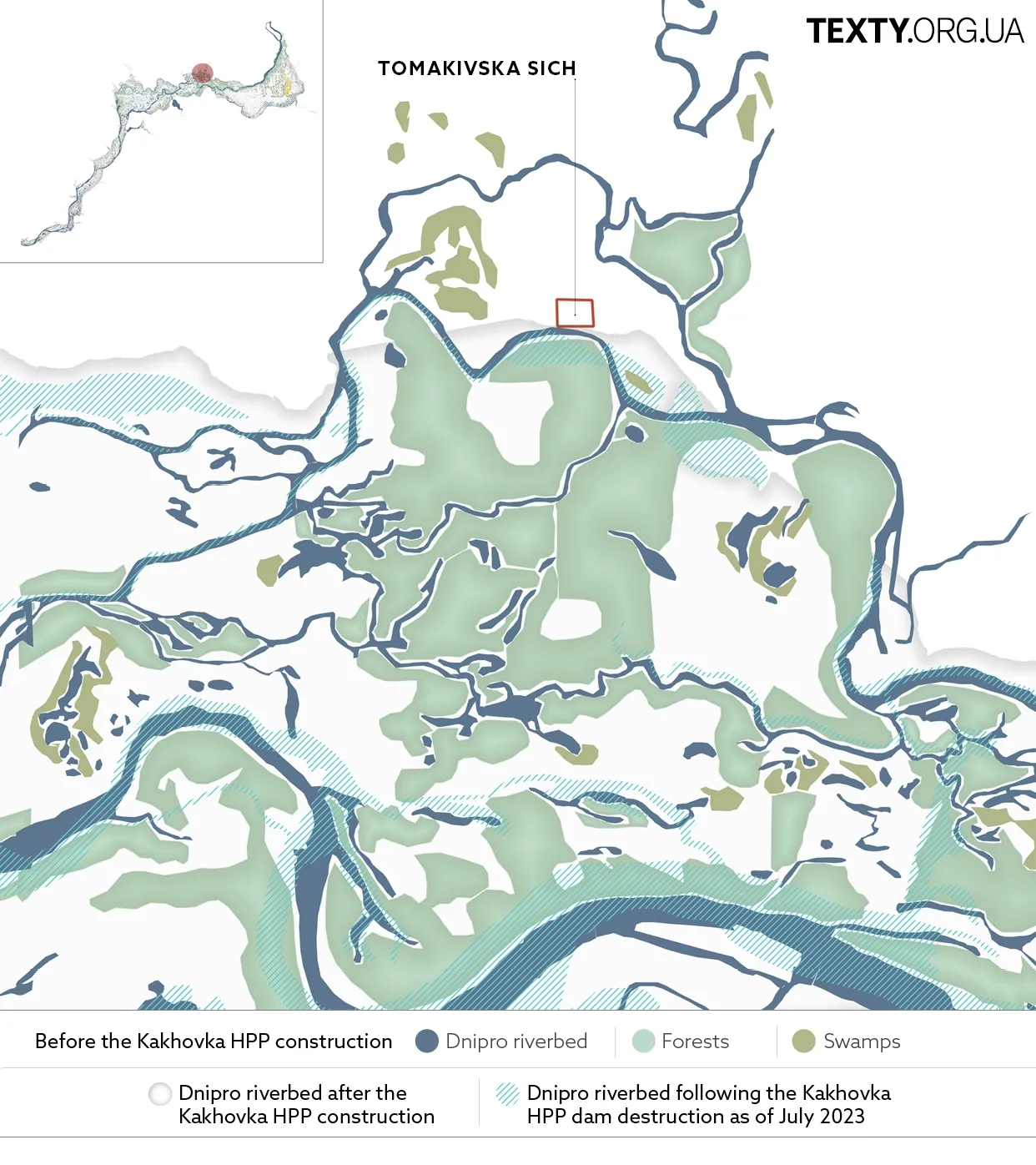

Tomakivska Sich

The inaugural Sich was established in the heart of the floodplains on the island of Tomakivka in the late 16th century. At that time, the number of Cossack army reached 10,000. After the uprising of Kryshtof Kosynskyi in Kyiv, Podillia, and Volyn in 1591-1593, there was a surge of people willing to join the Cossacks.

A huge forest blanketed Tomakivka. Tall pear trees grew on the outskirts, and centuries-old oaks were in the centre. The description comes from the stories of the cartographer Beauplan, who depicts the island as a wooded area spanning a third of a mile.

Tomakivska Sich was built in low-lying floodplains intersected by rivers. From the southwest, the island bordered the Bugai River, which stretched 10 km long. The meandering Revun River flowed from the east, turning into the 8-meter-wide Revuncha branch from the southeast. On the western side, the island was adjacent to the Chernyshivka estuary. There were also large lakes adjacent to Tomakivka: Spychyne in the north, Kalynuvate in the southeast, and Solomchyne in the south.

The villagers would take their livestock - cows, horses, and pigs - to Tomakivka, allowing them to graze freely for the summer.

In 1953, part of Tomakivka was flooded.

The reservoir submerged approximately 2.8 hectares (7 acres) of meadows, forests, hayfields and arable land. In addition, by various estimates, up to 100 villages were either partially or entirely washed away. A staggering 37,000 residents fled their homes and had no choice but to search for a new shelter.

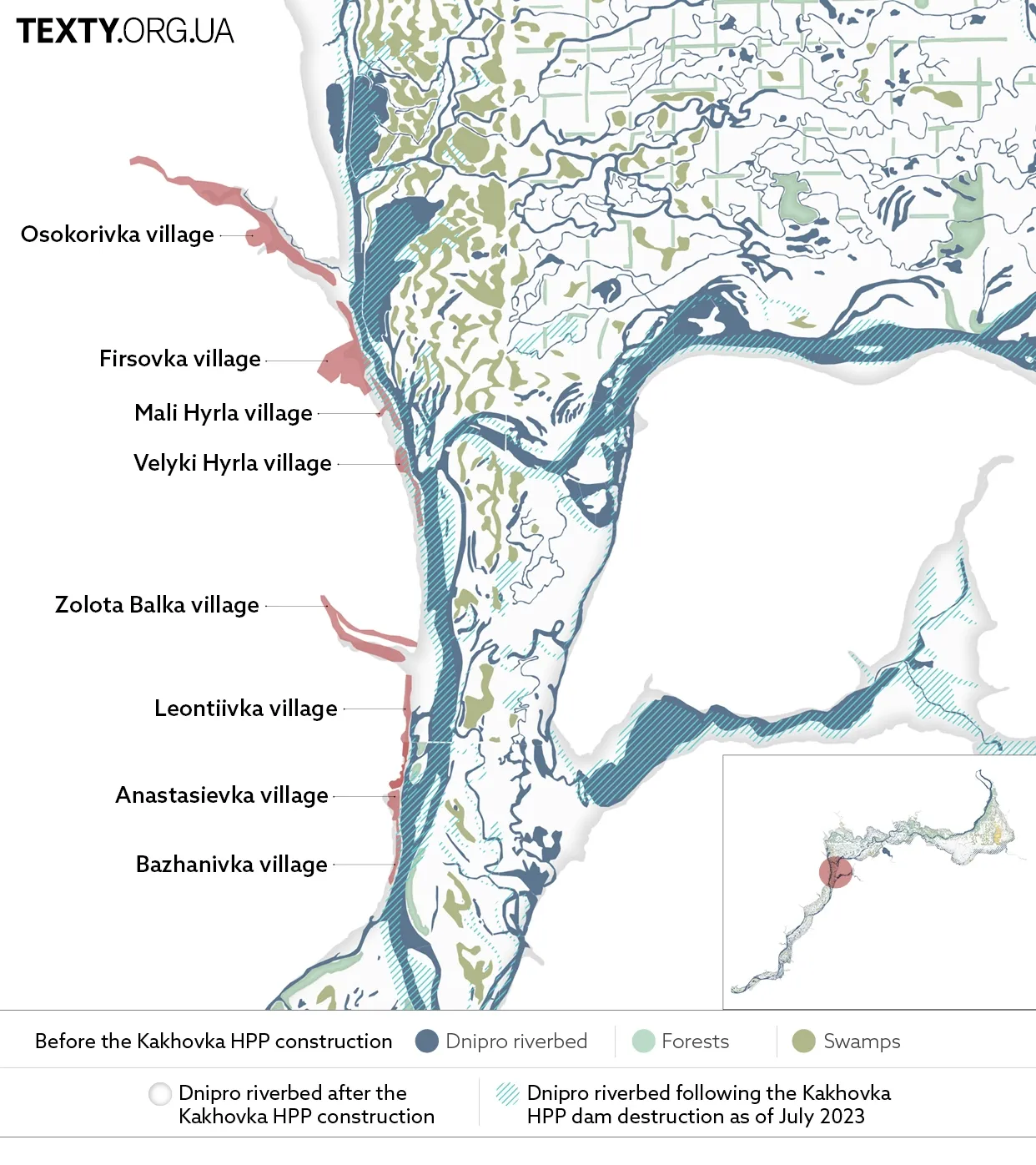

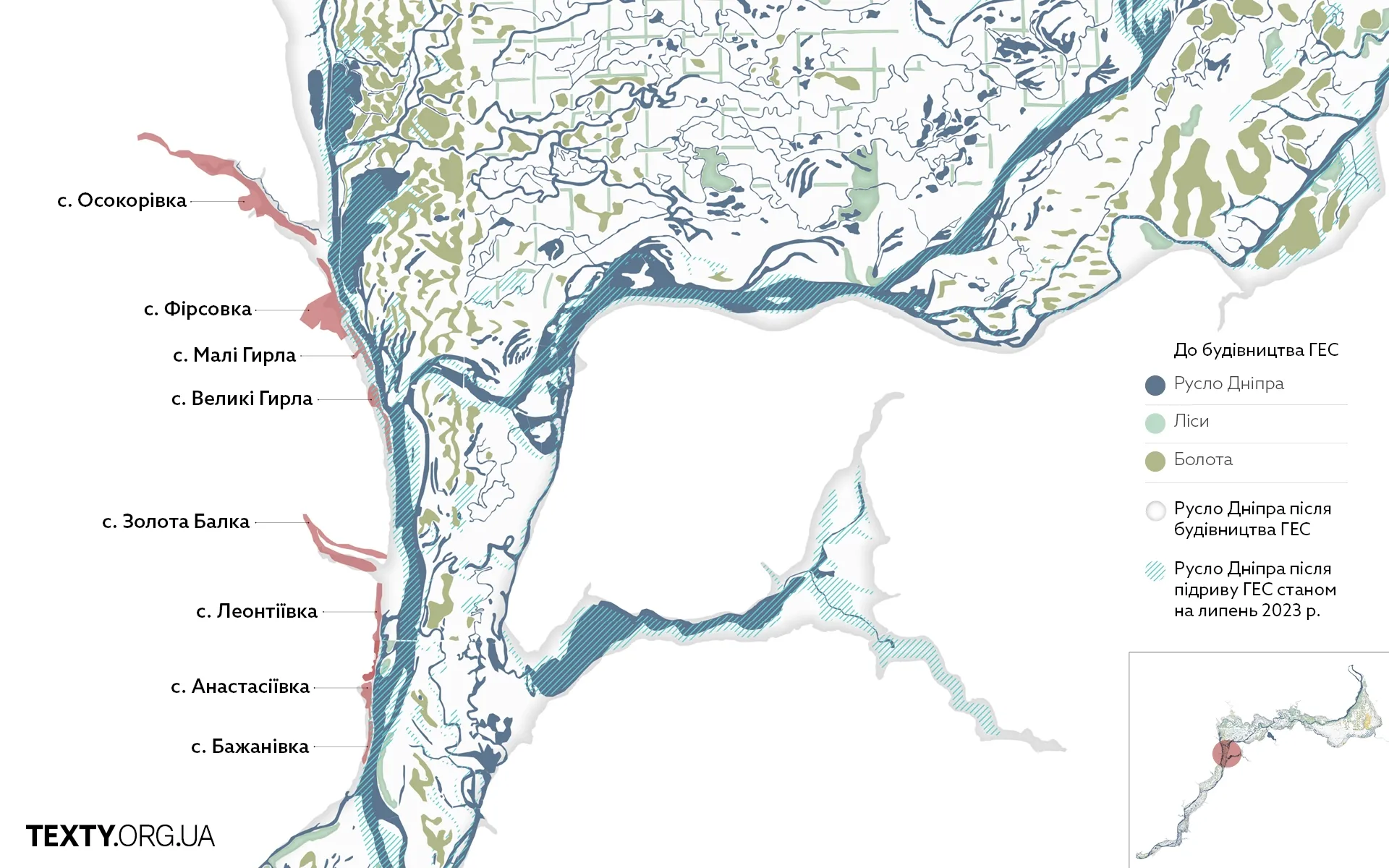

What was life like for people near Velykyi Luh before the disaster? Read on to explore the examples of Zolota Balka, Velyki Hyrla and Mali Hyrla.

Zolota Balka

Perched alongside the Dnipro River, Zolota Balka, meaning “Golden Beam” in English, overlooked scenic vistas of meadows, endless plains, numerous rivers and islands boasting fertile black soil. Every spring, the meadows around the village would flood, and the water would bring trees and branches to the shore. People collected this driftwood to heat their homes during the winter.

The floodplains near Zolota Balka after the war. Photo by Viktor-Mykolai Serdiuk

The floodwaters receded by mid-June, leaving behind nutrient-rich silt. In these treeless areas, people cultivated vegetables and potatoes, tended to their cattle, and harvested hay.

During the dry seasons, the water in temporary reservoirs would vanish, granting locals access to the lush forests and shrubs. Wood was used for construction and firewood, and wicker for baskets and wicker furniture. People used reeds to make fences and slabs for roofs.

The rich nature of Velykyi Luh saved the local population from starvation from 1932 to 1933 during the Holodomor – the famine inflicted on Ukraine by the Soviet regime. The villagers foraged water nuts and edible roots, ground them into flour, and baked pancakes known as “lyndyky”. They caught perches, pikes, bream and other fish in the lakes adorned with water lilies and bushes.

The area around Zolota Balka was gradually flooded by 1954. Many villagers sought refuge in other countries, while some stayed in the houses provided by the Soviet government on higher ground, beyond the reach of water.

Velyki Hyrla and Mali Hyrla

Before the war, people in Velyki Hyrla (Large Estuary) made beautiful furniture from wicker that was harvested from the nearby floodplains. The branches were boiled in a cauldron, and the bark was stripped off. These prepared materials were transformed into beautiful armchairs, chairs, sofas, and shelves. The finished furniture was delivered to Kherson for sale. Even during wartime, furniture was transported to surrounding villages.

As steamers sailed between Zaporizhzhia and Kherson, they would pass by the neighboring Mali Hyrla (Small Estuary). There was a market on the pier where locals sold cucumbers, tomatoes, watermelons, and melons to the passengers. The fresh produce quickly sold out, and people tallied their earnings.

Life in Velyki and Mali Hyrly was bustling. But in the 1950s, both villages were permanently submerged by the waters of the Kakhovka Reservoir, and the residents left.

Hrushivskyi Kut

Hrushivskyi Kut served as the winter quarters of the Zaporizhian Sich otaman Ivan Sirko, who lived here at the end of his life, doing beekeeping at the large apiary. Sirko died in the summer of 1680.

The "Chronicle of Samiylo Velychko", who was the first historian of the Ukrainian Cossack state, quotes:

"In the summer, on August 1, the esteemed Cossack otaman Ivan Sirko passed away at his apiary in Hrushivka, having been ill for some time. He was laid to rest with honors, with great cannon and musketry salutes, and with great sorrow from the entire army. For he was a devoted and accomplished leader who, from his youth until his old age... not only fought bravely for Crimea and burned some of its cities but also defeated numerous Tatar units in the wild fields and liberated prisoners."

The Cossacks transported Sirko's body to the Chortomlytska Sich and buried him with proper honors.

In the 1950s, the historic village of Hrushivskyi Kut was flooded by orders from the Soviet government.

Orliv Island

Around 1845-1846, the Dnipro River shifted its course near Nikopol, leading to the formation of an open space with clean sand right between the old and the newly created river branches.

On weekends, the townspeople would cross to Orliv Island (The Eagle’s Island) by boat for a small fee. People came here in groups, families, or alone, finding refuge from the sun under the shade of fruit trees. In the summer heat, there was no better place to relax in all of Nikopol.

Orliv Island disappeared beneath the waters of the Kakhovka Sea in 1954. However, after the Russian forces blew up the Kakhovka hydroelectric power plant’s dam in 2023, the island gradually resurfaced.

Novopavlivka

Novopavlivka emerged on the site of the Cossack village of Lysa Hora (The Bold Mountain). After the destruction of the Sich, the Russian Empire renamed the village Novopavlivka and resettled its soldiers there. After the construction of the Kakhovka hydroelectric power plant, most of the village was inundated. The site where the villagers' houses once stood is now home to the Velykyi Luh children's camp and serves as the recreation area for a ferroalloy plant.

Ivanivski sand drifts (ZNPP)

The Ivanivski sand drifts is a hilly area on the bank of the old Dnipro riverbed, where the ZNPP is now located. The mounds were shaped by the flow of a branch of the Dnipro River, which was redirected into a cooling pond during the construction of the nuclear plant.

High slopes trace back to the Ice Age when the glacier movement sculpted such landforms. The meltwater brought a lot of sand, clay, and gravel, forming high hills and dunes on the river terraces.

But it was not a desert. The Konka River flowed at the foot of the piles. The local open spaces were overgrown with impenetrable reeds and willows. There were many lakes and swamps. All this created dense floodplains.

Where did the sand drifts go? In 1970, the construction of the Zaporizhzhia State District Power Plant began. First, a workers' village named Enerhodar was founded two years later. The hills underwent partial levelling and construction. Coniferous trees were planted to prevent dust storms from covering everything around.

In his memoirs, Rem Henoch, the construction manager of Enerhodar and Zaporizhzhya NPP, describes the transformation as follows:

"The sand drifts were sandy hills up to 20 meters high. Foresters tried to plant them with pine seedlings for many years. But the winds shifted the sand, and the trees did not have time to take root. One of the enthusiasts developed a special tree-planting method using deep trenches. This allowed the main root of the sapling to grow faster than the moisture around it dried up, helping pines to take root."

Kuchuhurske settlement

Situated 30 km south of the modern city of Zaporizhzhia, Kuchuhurske was the largest Tatar settlement in the lowland floodplains of the Dnipro River, serving as a vital hub for transit trade along the Silk Road in the 14th century.

In 1953, on the eve of the construction of the Kakhovka hydroelectric power plant, Soviet archaeologists explored the remains of this ancient city within an area of 10 hectares (approximately 25 acres). Structures such as a mosque, bathhouse, brick Tatar houses, a palace, and other buildings belonging to affluent citizens were unearthed on the territory of the Kuchuhur settlement. They found 200-gram ingots for minting coins and Korean and Central Asian bronze mirrors.

Other things also point to the Silk Road: celadon porcelain vessels. At that time, they were made exclusively in the Chinese province of Longquan.

According to Oleh Vlasov, a researcher at the Khortytsia National Reserve, in 1360-1374, the area of the Kuchuhur settlement was known as the city Ordu, or Shehr al-Jedid, serving as the seat of Khan Mamai. The coins bearing the names Ordu (Bet), Ordu al-Jedid (New Bet) and Ordu al-Muazzam (Greatest Bet) were discovered at the site.

In 1374, a great drought struck the region,leading to famine and epidemics. As a result, Mamai's hordes left Velykyi Luh and retreated to Crimea.

Kamianske settlement

The Kamianske (Stone) settlement is located in the area of a modern-day pier in the city of Kamianka-Dniprovska, Zaporizhzhia region. According to Herodotus, this hilly cape was the center of Great Scythia in the 6th to 4th centuries BC. The capital, known as Metropolis, spanned 12 km² and was protected from attacks from the steppe by a two-meter earthen rampart and ditches.

In 1900, the settlement was discovered by a local teacher named Serdiukov. Subsequently, the Soviet archaeologists unearthed the ruins of frame farmsteads, half-hearted dwellings, bronze foundries, and craft workshops. They also found houses made of burnt bricks of the "Tatar type" and Juchid coins, which indicates the presence of the Golden Horde in this area.

Most of the ruins of the Scythian capital were submerged by the waters of the Kakhovka Sea.

Is it worth inundating the area once again?

The government of Ukraine plans to complete the dam's reconstruction and inundate the areas where Velykyi Luh once stood. In our opinion, this is not the right course of action. After all, these lands are extremely valuable for the self-identification of Ukrainians; decisive historical events took place here, with the Sich Cossacks playing a significant role in the formation of the modern Ukrainian nation.

From an economic perspective, the contemporary approach involves the extensive restoration of the riverbeds to save water, mitigate climate change and allow the recovery of natural ecosystems. The Kakhovka Reservoir used to irrigate lands which are now under the Russian occupation in the Kherson region.

However, after the liberation, it is recommended to discontinue the use of the open canals that previously supplied water for irrigation, as the delivery of water through these canals leads to significant losses due to evaporation and seepage in poorly concreted areas. It is also worth reconsidering the type of crops grown in irrigated areas and opting for those requiring much less water. Israel’s experience in these matters can serve as a valuable guidepost after deoccupation.

Additionally, it is worth setting up desalination plants along the Black Sea coast. The price of water should be taken into account, but in Israel, such plants are actively operating. Even if the cost surpasses that of rebuilding the dam, it is preferable to pay more in order to preserve and restore areas of extraordinary historical significance and value.

To zoom in on the map and take a closer look, click on the "START" button at top of the map.